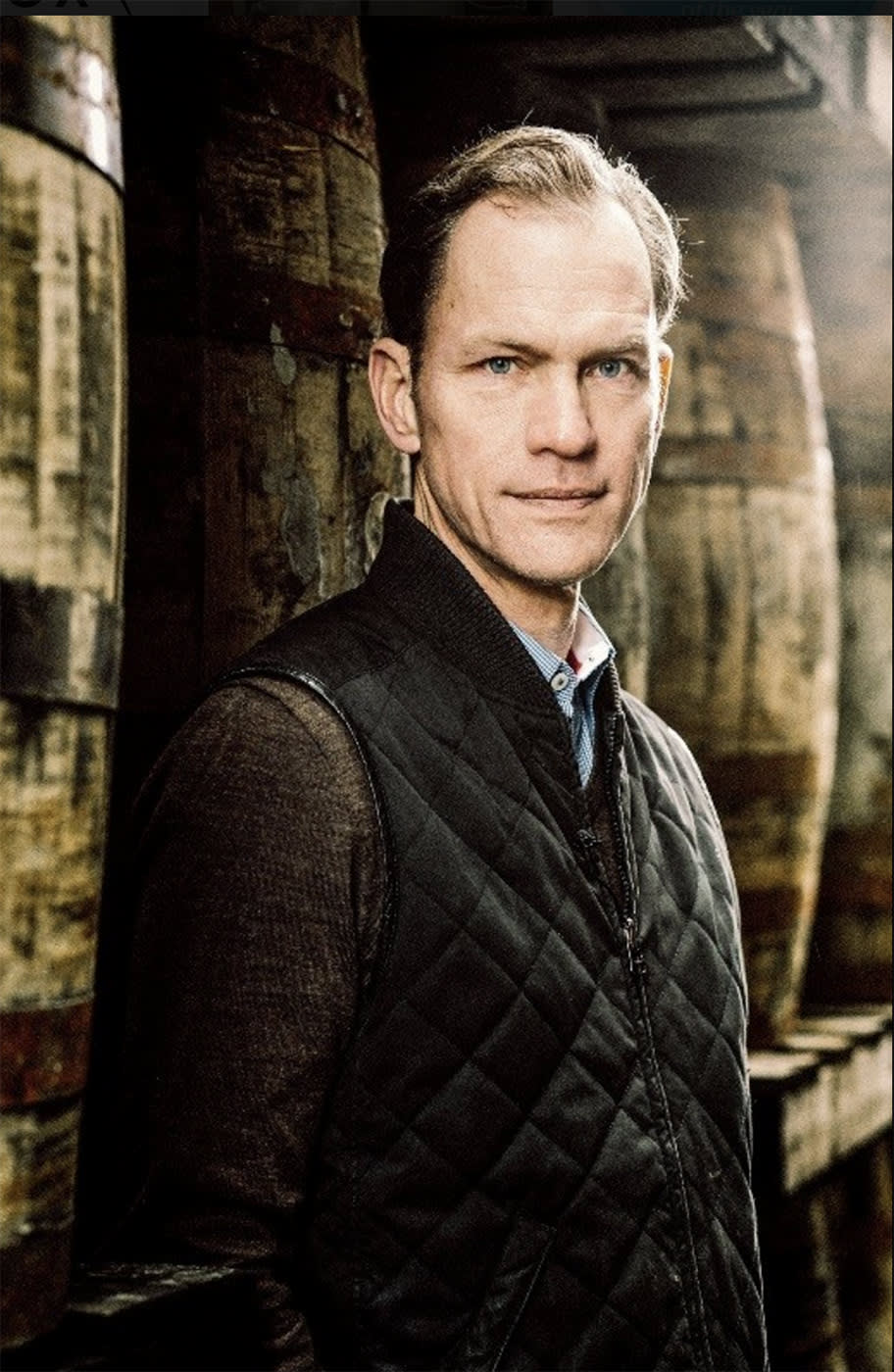

John Glaser is the last person I would call an outlaw. He’s more Clark Kent than Lex Luthor, but a few years ago he found himself on the wrong side of the law.

It was particularly surprising, since Glaser runs a boutique Scotch whisky company called Compass Box, and that’s where the outlawry took place.

The trouble began when he came up with a new idea about how to age whisky. He decided to attach fine-grained, toasted French oak (quercus petraea) staves to the inside of a used whisky barrel. He then refilled the special barrel with whisky and closed it up again for additional aging. The late Dr. Jim Swan, one of the foremost authorities on aging whisky, had suggested the practice to Glaser, which was based on a common wine technique.

“We were trying to replicate the effect of a new barrel,” Glaser recalls. He released the resulting spirit as The Spice Tree, a nod to the spicy notes imparted by the French oak.

While there may only be a few basic rules for making Scotch, they are rigorously enforced by the Scotch Whisky Association (SWA). And the SWA was not amused by Glaser’s unusual aging methods, nor were they fans of The Spice Tree. Glaser argued to no avail that traditions evolve, and this was an evolution of tradition. It didn’t fly.

“We stopped using the inserts when it became evident we’d end up before a judge,” Glaser says.

Credit Facebook

A few French oak slats hardly seem like a big deal or the grounds for a legal battle, but the new frontier for whiskey makers is the type of wood that their spirits age in. While the barrel has always been important, I’ve seen a huge increase in experimentation during the last few years that has led to the creation of an array of interesting whiskies.

But the use of a white oak barrel by whiskey distillers around the world is, of course, still standard and using any other wood, even a different type of oak, meets with resistance that ranges from suspicion to legal action.

There are very good reasons why white oak is favored: It is plentiful, strong and it doesn’t leak. It will, however, allow a certain amount of oxygen to pass in and out, crucial to the whiskey aging process, and in the case of white oak, provides a host of familiar flavors to the whiskey—vanilla, caramel, coconut.

However, white oak’s familiarity and reliability is both a blessing and a curse.

Take best-seller Maker’s Mark. After years of work and millions of dollars spent ensuring that every bottle of its bourbon was exactly the same, consumers’ thirst for new products was leaving the brand behind. After weighing various options, Maker’s turned to Independent Stave Company (ISC), for help creating an enhanced version of its bourbon. ISC’s answer? A system of barrel inserts made from air-seasoned, seared French oak staves. The liquor produced in these special barrels ultimately became Maker’s 46.

One small problem: The system only worked well in the winter, at temperatures under 50°. (When the whiskey got warmer than that, it would penetrate too deeply into the wood, picking up undesirable flavors from the raw oak.) The company decided to dig a cave out of the limestone hill on the edge of the distillery, to enable year-round aging of Maker’s 46.

Credit Facebook

That came in handy when Maker’s decided to take this idea further with their Private Select Barrel Program, which allows stores and bars to create their own version of 46. In addition to the seared French oak, ISC came up with several other types of slats that can be added to a barrel to customize it. (As a guest of the company, I tried my hand at making a barrel a couple of weeks ago.) Each stave delivers a different characteristic and there are literally hundreds of variations that can be created.

But Maker’s is hardly alone in coming up with wood innovations. There are few people more interested in this topic than Dr. Don Livermore, the master blender at J.P. Wiser’s (the huge whisky distillery in Windsor, Ontario), whose doctorate is in wood/whisky interactions. He currently has a project going where he uses red oak (quercus rubra) barrel inserts. Canadian whisky is traditionally a blend of individual whiskies made from different grains, blended after aging, and Livermore found that the red oak—a strongly-flavored wood; “think very spicy cedar,” he said—works best with a rye-based whisky.

I tasted the red oak whisky about four years ago; it was strongly-flavored indeed, almost eye-watering. At that strength of character, it’s surely going into a blend—that’s what Canadian distillers do, after all—but Livermore noted that bartenders gravitated to the straight stuff when sampled on it. “They’re already thinking about blending it—in a cocktail,” he reasoned.

There’s also another Canadian wood project that has been going for about six years for Collingwood Whisky. This project grew out of research done on new types of barrels at the cooperage owned by the brand’s parent company Brown-Forman. Maple was one of the woods tested, and while it didn’t make a great barrel, the effect on the whisky was noticeable; a pleasant but not overwhelming maple sweetness, and a reduced astringency. (Another Brown-Forman brand, Woodford Reserve, did release a limited-edition whiskey aged in a maple barrel several years ago.)

A decision was made to “rest” the Collingwood Whisky on toasted maple staves. How do they do it? The mature whisky is stored in a stainless-steel tank and the special staves are then inserted into the alcohol. It’s a technique that could be used with a variety of different woods.

Meanwhile back in Scotland, The Spice Tree is back on the market. Glaser worked with Scottish coopers to add a thin slice of toasted French oak that's held in place against the barrel head by a groove in the staves. The SWA had nothing to say about this new “evolution,” and it was approved for sale.

Glaser is pleased that his project is once again on store shelves. “You can get exotic flavors from this wood, a new spectrum of flavors that you just can’t get from white oak,” he said. “Better wood makes sense.”