Mississippi, 1863. The men of G-Company in the 95th Illinois Voluntary Infantry must have cheered loudly as ‘Little Al’ Cashier clambered up the tree, pulled off the tattered, gun-shot Union flag and hoisted a new one.

Or maybe they held back their applause until he was down again, safely out of sight of the Confederate snipers. Either way, all were agreed that Little Al was as courageous a soldier as any of them.

A third of G-Company were dead by the end of the U.S. Civil War, killed in action or prey to the virulent diseases that swept the lines. Far fewer were still alive in 1913, nearly 50 years later, when word reached them that Little Al had been incarcerated in a state psychiatric institution.

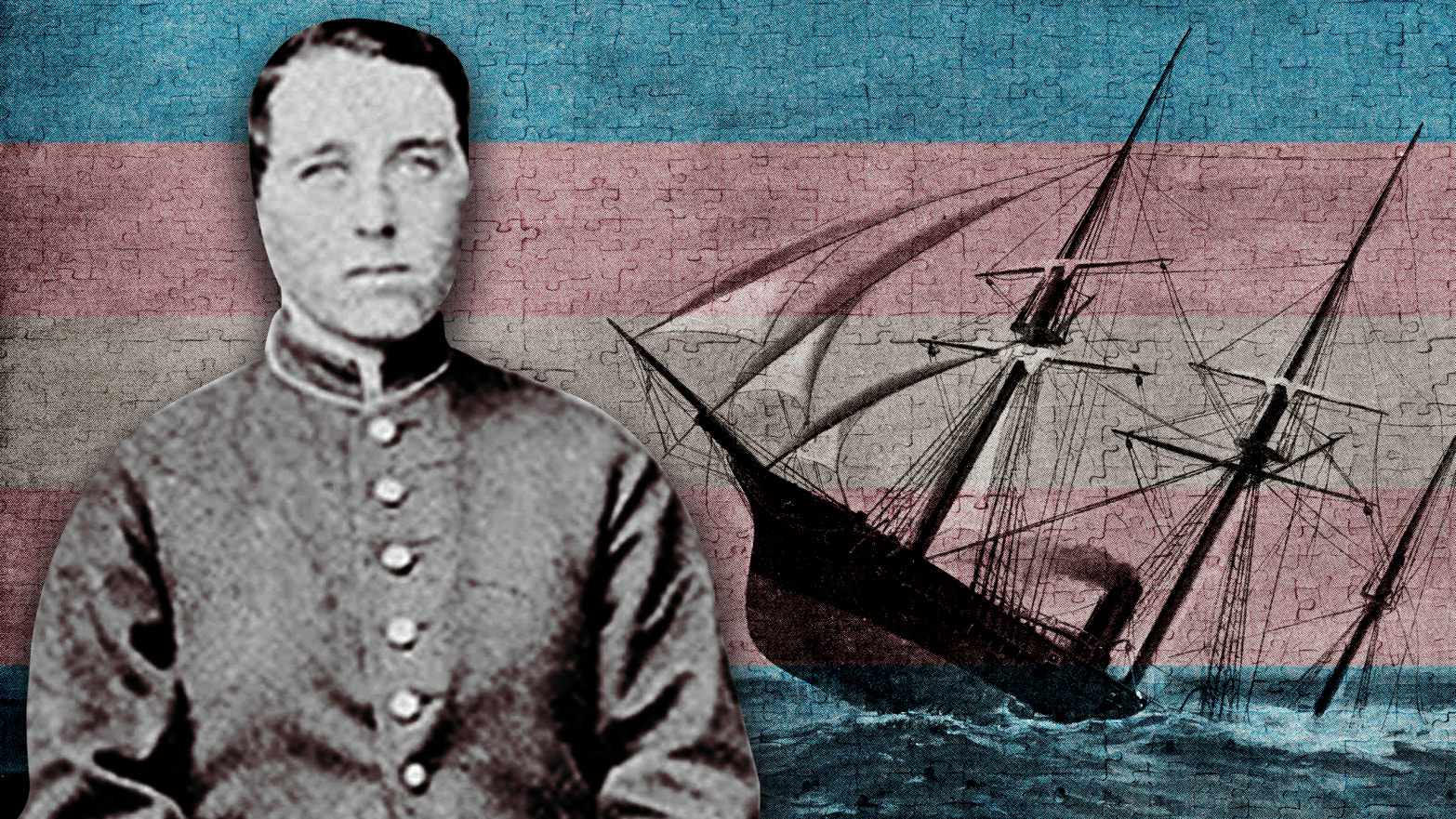

That might have been shocking enough but an infinitely greater surprise was in store; it transpired that Private Albert Cashier was assigned female at birth.

In the wake of Donald Trump’s order that the U.S. military no longer accept transgender individuals as recruits, it seems a fitting time to acknowledge the extraordinary life and times of Civil War veteran Albert Cashier, born Jennie Hodgers, who was the subject of a ‘We’ve Been Around’ documentary last year.

Born in Ireland in about 1842, Albert Cashier is regarded as among the first known examples of a transgender person in American history.

It is important to note that the concept of being transgender was effectively unknown in the United States at this point, although some Native American tribes did assign third-gender roles, which are sometimes described under the term ‘Two-Spirit.’

In the annals of transgender people in the U.S., the first documented person to challenge gender binary roles was Thomas(ine) Hall, who was living in Virginia in the 1620s. Hall dressed alternately in both men's and women's clothing but following a sexual controversy, Hall was subjected to a physical inspection.

Brought before the Quarter Court in Jamestown, Hall was adjudged to be both a man and a woman and ordered to wear both a man's breeches and a woman's apron and cap simultaneously.

Born over two centuries later, Albert Cashier was reputedly the daughter of Patrick Hodgers, an Irish coachman and horse trader from Clogherhead, County Louth, and his wife, Sallie. Further details about his early life in Ireland are unknown but it is assumed that he was illiterate; he signed all identified documents with an ‘X’.

Nor do we know when he emigrated to America; it is rumored he arrived as a stowaway, quite possibly direct from the Irish port in Drogheda.

One theory holds that he went to work at an all-male shoe factory in Belvidere, Illinois, which was run by an uncle and that it was from this point that he began identifying as Albert Cashier.

Public Domain

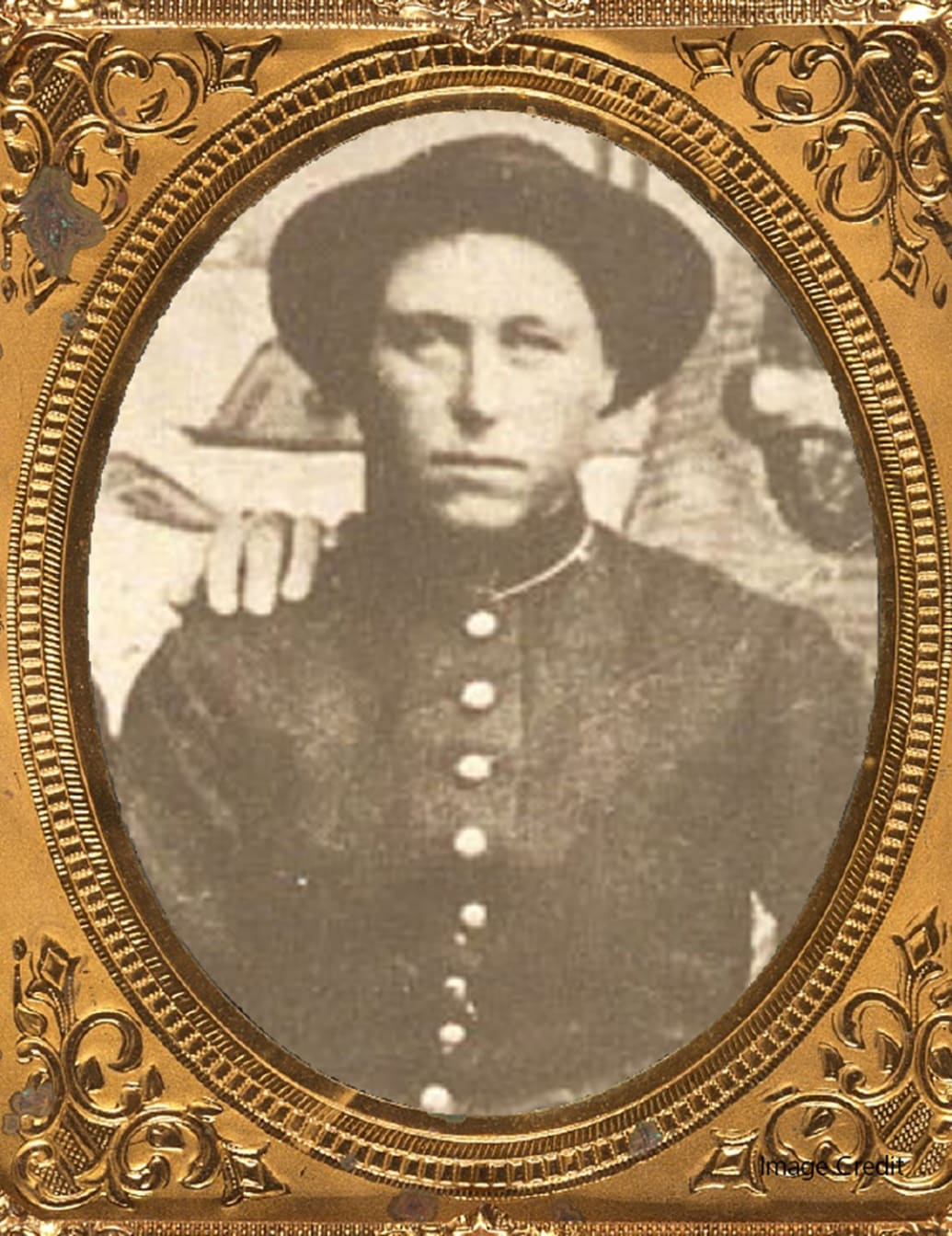

By the summer of 1862, the U.S. Civil War was underway and Congress authorized the drafting of a new militia for the Union Army. Over 144,000 Irish answered the call, including 20-year-old Al who went into the recruiting depot at Belvidere on 6 August 1862 and enlisted in the 95th Illinois under the name of Albert D. J. Cashier.

Nobody suspected a thing; Captain Elliot Bush, his company commander, merely noted that the five-foot-three private was the smallest of the new recruits.

Al was one of at least 250 (assigned-at-birth) women who dressed in the baggy clothes of a male soldier and went to war. He is also believed to be the only one who survived the entire war, undiscovered, and who consequently went on to receive a military pension.

One can only speculate at Al’s motives: the army offered a reasonable salary and the prospect of a pension if you completed your service.

Al’s motives for reinvention are unknown, although several of his neighbors in later life maintained that he had been following a sweetheart who was subsequently killed.

'Little Al Cashier,' as his comrades nicknamed him, managed to keep his secret for 50 years. Surviving testimonies of fellow soldiers in G-Company after the truth came out reveal that they just thought of him as aloof and a little feminine.

Most of them subsequently referred to him as a female, as the concept of referring to someone by the way they identified was not understood until much more recent times.

"We never suspected that ‘Albert’ was not a man," remarked Corporal Robert Horan of G-Company. "But we did think sometimes that she acted more like a woman than a man. For one thing, she always insisted on bunking by herself. And she did lote [lots] of washing for the boys—she used to wash our shirts. When the strangeness wore away she made a good comrade. She was a soldier with us, doing faithfully and well."

"I never suspected anything of that kind," concurred Corporal J. H. Himes of the same company. "Albert D. J. Cashier was very quiet in her manner and she was not easy to acquainted with. I rather think she did not take part in any of the sports and games of the members of the Company."

It was Charles W. Ives, his company sergeant, who recalled how Little Al hoisted the Union flag despite the high risk of being shot by a sniper. On another occasion, the blue-eyed, auburn-haired soldier leapt onto a fallen tree-trunk and began jeering at his Confederate opponents on the other side of the battlefield.

Nyttend/Public Domain

"Al did all the regular duties," Sergeant Ives recalled. "Not knowing that she was a girl, I assigned her to picket duty and to carry water just as all the men did. One time, we went into barracks … All of the bunks were double, but over in one corner there was a single cot. Cashier asked me if he might have the cot. I consented and thought nothing of it."

He often sat apart from the others, puffing on a pipe. On account of his short stature, he wasn’t able to carry as much as other men, but his fellow soldiers never failed to help him out, in return for which he looked after the laundry and mending clothes.

By the time he mustered out of the army on 17 August 1865, Al had traveled nearly 10,000 miles, including 1,800 on foot. He had also seen action in 40 different battles and skirmishes fought in states such as Mississippi, Louisiana, Missouri and Tennessee. This included the Red River Campaign, the Battle of Atlanta and the Battle of Guntown, Mississippi, in which Captain Bush and many other members of him regiment were killed.

He also served at the Siege of Vicksburg where he was briefly captured by a Confederate soldier but somehow managed to grab his gun, knock him down and scarper back to his own lines. When Vicksburg fell, he was one of the first to victoriously march into the Mississippi city. Private Albert Cashier’s name is among 36,325 Illinois soldiers immortalized on the bronze plaques at the elaborate Illinois victory monument in Vicksburg.

After the war, Albert Cashier continued to identify as a man and he did so for the remainder of his life. By 1868, Albert Cashier had moved from Belvidere to the small village of Saunemin, Illinois, south-west of Chicago, where he worked as a general handyman, gardener, janitor, lamplighter and, later, chauffeur.

As a man, he also had the advantage of being able to open a bank account and vote, long before women had such a privilege; presumably his military papers sufficed for identification purposes. He worked closely with the Cheesbro family, whose support enabled him to build a small timber house; a replica now stands on the site and is an increasingly popular tourist destination.

He also joined the Grand Army of the Republic, the largest organization of Union Veterans, which enabled him to reunite with his comrades from the 95th, which he frequently did in ensuing decades. As one Saunemin citizen recalled: "On Decoration Day [Private Cashier] always wore his uniform and led the parade, proudly carrying the big flag as slight as he was. He was in his glory when he did that."

Another neighbor appears to have been a little charier: "Many times he came to our place to stay a while, and he could rock my baby daughter to sleep better than we could. He would go uptown and bring him the most beautiful things, such as dress goods. We always wondered where he got such a feminine taste."

In 1911, Al was fixing a car for former State Senator Ira M. Lish when the latter accidentally drove over him and fractured his leg. He was taken to the Soldier and Sailor’s Home in Quincy, Illinois, where his anatomical sex was revealed. Both the senator and Dr Leroy Scott, the doctor at the home, agreed to keep it quiet but slowly it leaked out and by 1913 his extraordinary story had been disclosed to the world, including the Irish press.

TradingCardsNPS/Flickr Creative Commons

The news caused much astonishment among the surviving members of his battalion. They had frequently mocked Private Cashier for his lack of facial hair and his compact height but none appear to have suspected the truth. More importantly, they were unanimous in their support of him, hailing his courage throughout the war and applying so much pressure that the Bureau of Pensions concluded that there was no option but to continue paying him $12 a month pension.

Sadly Al’s mind was in decline by then, possibly triggered by the trauma of the accident and the global fascination in his remarkable secret. In March 1914, the County Court diagnosed him with advanced dementia and sent him to reside at the Watertown State Hospital.

He was placed in a female ward and ordered to wear a dress. The hospital recorded his condition on arrival as "no memory, noisy at times, poor sleeper and feeble.’ Corporal Robert Horan was skeptical about the hospital’s motives; ‘they don’t care for Cashier, it’s his money there [sic] after."

When former Sergeant C. W. Ives visited, he remarked: "I left Cashier a fearless boy of 22…when I went to Watertown, I found… a frail woman of 70, broken because, on discovery, he was compelled to put on skirts."

It is notable that his former comrades-in-arms, born in the 1830s, evidently had a much more inclusive, compassionate and accurate understanding of Albert's gender identity than the early 20th-century doctors who insisted he wore a dress during the last years of his life.

A correspondent for the Hartford Republican described "his face as a face for a painter to dwell on; half a century of sun and wind had bronzed that face, sowed it with freckles and seamed it with a thousand wrinkles."

Al died aged 72 on 10 October 1915. He was given a funeral with full military honors in East Moline before his body was shipped back to Saunemin where he was buried in a space the Cheesbro family had reserved for him in their plot.

The headstone reads: “Albert D J Cashier, Co. G 95 ILL. Inf, Civil War. Born Jennie Hodgers in Clogher Head, Ireland 1843 - 1915.”

His death was also reported in the Irish press, most notably by in the Drogheda Argus (1915) which read: ‘If there are any friends of the old lady still about Clogherhead, they should forward the particulars of their relationship to [Mr J. E. Andrews, Superintendent of the Soldiers and Sailors Home, Illinois], as he left considerable property and money behind him.’

Despite this succulent offer, no relatives stepped forward.