THE ADVENT OF BEATLES-INSPIRED HYSTERIA can be difficult to date, but the phenomenon we call “Beatlemania” got its name in a (London) Daily Mirror article that appeared fifty years ago this month. In this essay, excerpted from his book Beatles Vs. Stones (Simon & Schuster, Oct 29), author John McMillian explores the roots of the phenomenon.

How did the Beatles ever manage to inspire such frenzy in the first place? People used to ask them all the time, and even they weren’t entirely sure. When it comes to explaining Beatlemania—a phenomenon unlike anything the world has ever seen, before or since—it would seem that we’ve all been afflicted by a tremendous failure of collective discernment.

Hardly anyone disputes that the Beatles were talented, handsome, and charming. They also had the extraordinary luck to come along at precisely the right moment. Had any of the four been born just a few years earlier, the Beatles would not even have existed (since England didn’t abandon its compulsory National Service program until 1960). Thankfully, instead of being shuffled off to various military bases for two years apiece, the four were able to find each other and devote several years to playing music together, burnishing their chops in front of small but adoring audiences. By the time they finally began hitting their creative stride, the first wave of post-World War II baby boomers were reaching their teens. It was time of unprecedented economic prosperity in the West, and for many listeners, the Beatles’ joyous and optimistic music seemed as suited to the era as a soundtrack.

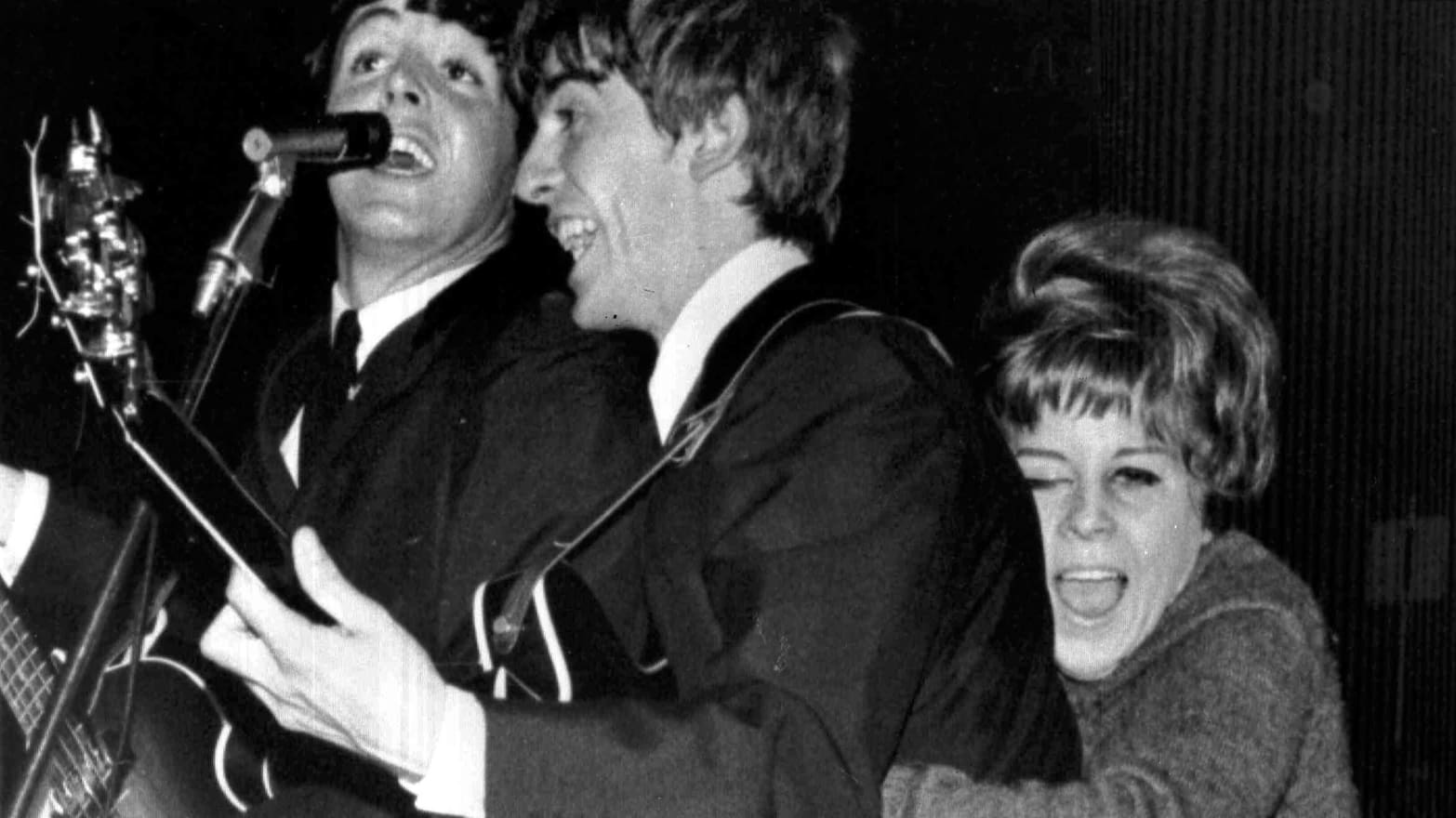

But this scarcely begins to explain the mass pathology that the Beatles inspired: teenage girls fainting, weeping, and peeing themselves en masse, even as battalions of policemen herded them behind fences and barricades. And always, of course: the screaming. It was more than a little disconcerting. Journalists compared the sounds made at Beatles’ concerts to the nerve-shredding cries of pigs being brought to slaughter, or to the screech that New York City’s subway trains make as they grind along the rails. When the group played Shea Stadium in 1965, the New York Times reported, the crowd’s “immature lungs produced a sound so staggering, so massive, so shrill and sustained that it crossed the line from enthusiasm into hysteria and soon it was in the area of the classic Greek meaning of the word pandemonium—the region of the demons.”

Nevertheless, it is clear enough that in addition to their great talent and fortuitous timing, the Beatles had some other unusual qualities that their younger fans found appealing. One is that, from the outset, they acted and behaved just as they saw themselves—as a tightly-knit group. Previously, in both England and America, most successful pop and rock acts emphasized individuals: either those who performed solo, like Elvis Presley, or who fronted a well known backing band, like, Buddy Holly & the Crickets, or Bill Haley & the Comets. British pop, especially, seemed beholden to a formula where a lead singer with a flashy stage name, such as Billy Fury or Marty Wilde, performed in front of a generic back-up group.

When the band we now know as the Beatles was first getting going, they easily could have put Lennon up front, and in fact they very briefly styled themselves as Johnny and the Moondogs. But they never seriously pursued that approach. Lennon later remarked that the day he first laid eyes on Paul—who at age fifteen already owned his guitar, on which he could perform a stellar rendition of Eddie Cochran’s “Twenty Flights of Rock”—he realized he’d stumbled into a dilemma. “I had a group [the Quarry Men],” Lennon said. “I was the singer and the leader; then I met Paul, and I had to make a decision: Was it better to have a guy who was better than the guy I had in? To let the group be stronger, or to let me be stronger?”

Lennon chose what was best for the group, and right away, he and McCartney struck up an energetic rapport. Oftentimes they would ditch school together in order to hang out at Paul’s father’s house, where the two taught each other what they knew about the guitar, and took their first stab at co-writing songs. About a year later, in February 1958, Paul recruited George into the group. Though just shy of fifteen, Harrison looked to be only about twelve, and at first Lennon only barely tolerated him. “He used to follow me around like a bloody kid and I couldn’t be bothered,” Lennon said. “It took me years to come round to him, to start considering him as an equal or anything.” Eventually, though, the three discovered they shared an extraordinary musical and personal chemistry.

In contrast, drummer Pete Best rarely seemed to click with the others; he was said to be too ordinary, too slow, soft-spoken, moody, a loner. When the rest of the band got hopped up on speed in West Germany, Best stuck with beer; and when they started brushing their hair forward over their foreheads in the “exi” (short for “existential”) style admired by photographer Astrid Kirchherr, he kept his in a carefully sculpted quiff. The only reason the Beatles took him on in the first place, in August 1960, is because they desperately needed a drummer in order to be able to take up an offer they’d received for a steady engagement in Hamburg; Best was the only one they auditioned. Two years later, when they fired him, they could hardly have been any more coldhearted about it: they told Epstein it was his responsibility to break the bad news, and then they never spoke to Pete Best again. Considering all the work he’d put into the band, the poor guy must have been mortified.

Then again, no one sanely doubts that it was the right decision. In addition to being the better drummer, Ringo’s goofy looks, droll humor, and amiable nature all suited the Beatles just perfectly. There was something intangible in his personality—Lennon called it “that spark [that] we all know but can’t put our finger on”— without which the Beatles might never have cohered enough to be called “the Fab Four.” Nevertheless, when the Beatles launched their recording career at EMI, producer George Martin came perilously close to insisting that they follow the custom and designate one of themselves the front man: either John or Paul. As he mulled over which of the two should become the leader, however, he also considered how well the Beatles got along together, and how much he enjoyed their collective charisma. They “had that quality that makes you feel good when you are with them and diminished when they leave,” he once said. Finally, he decided he wasn’t prepared to force the issue if it might upset the group’s lovely alchemy.

As a result, when most fans were introduced to the Beatles, they saw an indivisible group in which each member nevertheless had distinctive attributes: John was typecast as the clever, intellectual one; Paul, the romantic charmer; George, quiet and mysterious; and Ringo, the easygoing goof. They’d been tested by adversity, and together they reached a level of success that was so extraordinary and improbable that they soon began suffocating under its weight, at which point they began forging an even tighter bond: the special camaraderie that came from being the only ones on the planet who truly knew, firsthand, what it was like to be a Beatle. As a result, their inner circle became virtually impenetrable. “They became the closest friends I’d ever had,” Ringo later said about the others. “We really looked out for each other and we had many laughs together. In the old days we’d have the hugest hotel suites, the whole floor of a hotel, and the four of us would end up in the bathroom, just to be with each other.”

The Beatles were also distinctive in the ways they related to their female followers. In his book Magic Circle: The Beatles in Dream and History, scholar Devin McKinney shrewdly observes that when the Beatles first touched down at New York City’s JFK airport, on February 7, 1964, the newsmen who covered the story all turned to military metaphors: the Beatles were “invading” and “conquering” America; they were “ruling” and “dominating” the music charts. “Had those reporters been women,” McKinney speculates, the “defining words of Beatlemania would have been different.” (Perhaps along the lines of “The British Seduction.”) Meanwhile, the Beatles arrived Stateside just as a gargantuan teen market was emerging, and American society was becoming increasingly sexualized. For reasons that even psychologists could not agree upon, the Beatles seemed to exude a kind of sublimated sexual energy, coupled with a tender sensibility, which left young girls absolutely obsessed.

Many commentators have alluded to the Fab Four’s unusual androgynous qualities. Beginning in the spring of 1961, the Beatles started experimenting with the call and response vocals, skirling harmonies, and falsetto leaps that were characteristic of the American “girl-groups” they admired, like the Shirelles (and later the Ronettes and the Shangri-Las). Few other male groups were as as steeped in the girl-group genre, or as comfortable embracing its clichés. The Beatles covered nine girl-group songs in their live performances, and five of these appeared on their first two LP’s.

Usually when the Beatles sang songs by girl-groups, they switched the relevant gender pronouns, but they didn’t do so in every case. When they performed the Shirelles’ song “Boys,” which was a staple of the Beatles live act from about 1961-1963 (it was their requisite “drummer number”) they sang the chorus just as it had been written, from a female’s perspective: “I talk about boys now! (Yeah, yeah, boys!) What a bundle of joy!” In a 2005 Rolling Stone interview, McCartney recalled that the song was a “fan favorite” (Pete Best had sung it before Ringo), though he added, “if you think about it, here’s us doing a song that was really a girls’ song. … Or it was [as the Beatles played it] a gay song. But we never listened. It’s just a great song. … I love the innocence of those days.”

More than other performers, the Beatles also had a habit of seeming to sweetly and directly address their girl fans through their use of personal pronouns (“P.S., I Love You,” “With love, from me, to you,” “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” and so forth). In fact, the Beatles’ second U.S. album, Meet the Beatles!, was packaged by Capitol Records so as to contain only songs about relationships. Once, when an American reporter asked Lennon about the Beatles’ heavy reliance of first person pronouns, he drew a sarcastic reply: “Should it be ‘I Want to Hold Its Hand?’” Lennon said. “Or, She Love Them?” But this was merely his way of obscuring the fact that he and McCartney were consciously writing formulaic songs that they hoped their young female listeners would personally identify with. It was a “little trick,” McCartney admitted. “We try to do that, you know, to make it personal.”

The Beatles also flavored some of their popular early songs with a dash of innuendo. A rough draft of the song that became “I Saw Her Standing There” went: “She was just seventeen / Never been a beauty queen.” McCartney recalls that Lennon laughed incredulously when he first heard it, and then he supplied the roguish “and you know what I mean.” And certainly it’s difficult, nowadays, to listen to “Please Please Me” as anything other than an exasperated plea for oral sex. But few of the group’s contemporary listeners had much to say about any possible sexual insinuations in the Beatles’ work. They projected sexual charisma, to be sure, but it was a charisma that was tamed and domesticated for their youngest female fans. More than anything else, teenagers seemed to swoon over tenderness and vulnerability that the Beatles expressed in their songs.

From BEATLES VS. STONES by John McMillian. Copyrights © 2013 by John McMillian. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.