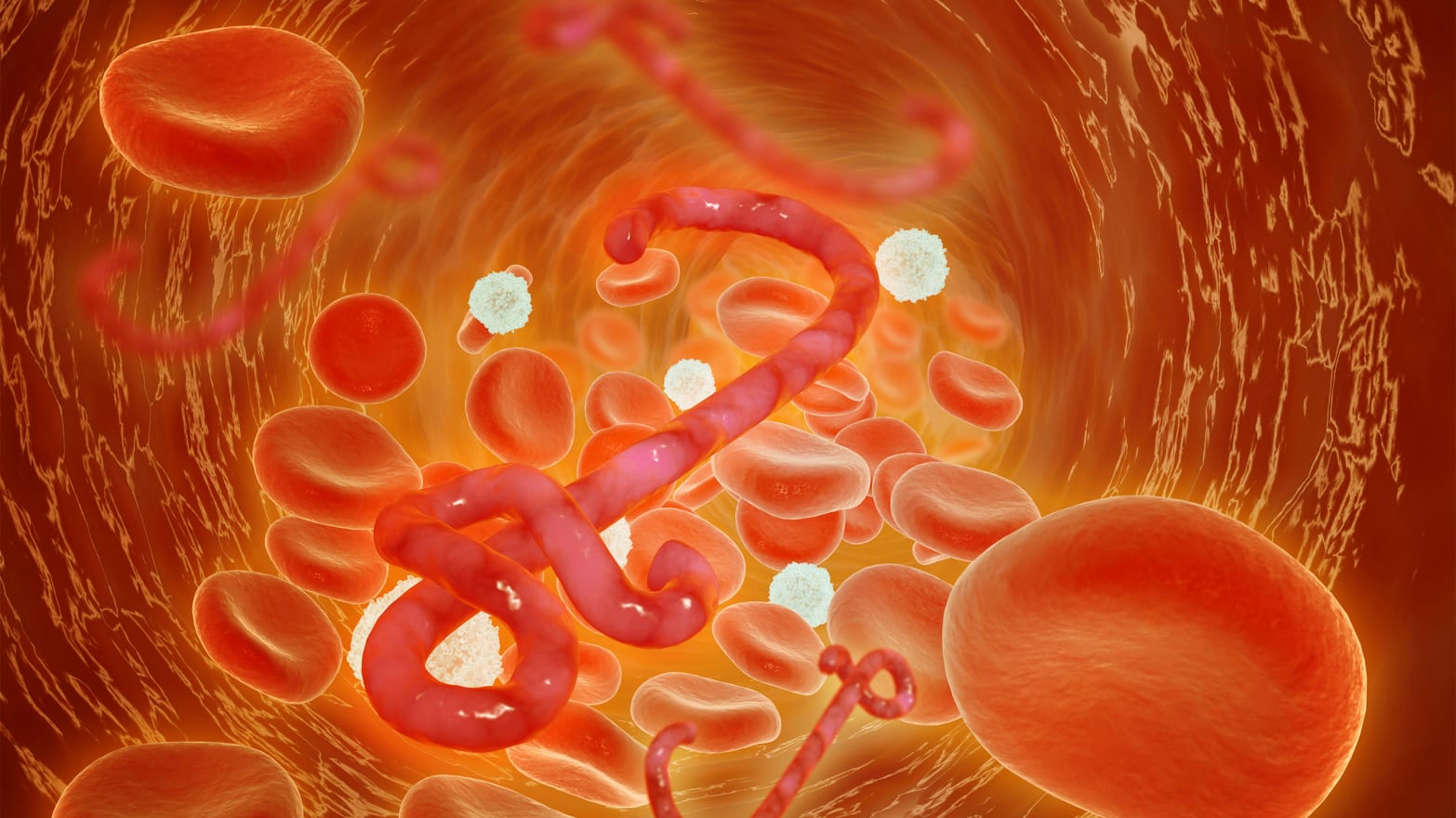

Ebola’s war on the body is waged in the blood.

Traveling through the bodily fluids of an infected person, Ebola enters through a mucous membrane or break in the skin. Once inside, the virus attacks a variety of cells that make up the body’s immune system, damages the lining of the blood vessels, and causes them to leak. In some cases, such as those of Dallas nurses Nina Pham and Amber Vinson, the body figures out how to fight back. It builds up anti-bodies to fight off the infection in the blood.

In others, it doesn’t. As the infection worsens, so too does the damage to blood vessels, which can may then induce hemorrhaging (internal or external) in the body. Eventually, if not stopped, this will cause a massive drop in blood pressure that puts the body into shock—leading to organ failure and, ultimately, death. Still the war is far from over. The blood of those who are killed by the virus is incredibly deadly, carrying upwards of 10 billion particles of virus in just one-fifth of a teaspoon of blood.

Early in the epidemic, the lethal blood of Ebola victims was the virus’s secret weapon—infecting unsuspecting family members who prepared, buried, or touched the body. With the anti-body rich blood of Ebola survivors, and its potential to save those suffering from the disease, we may be able to beat Ebola at its own game. This week, with the announcement of a $3.7 million grant for scientists to study the effectiveness of this treatment in Guinea, we’re already taking the lead.

The concept of transfusing the blood plasma of a survivor who has built up immunity to the disease into a sick patient, reemerged in mainstream conversation in August when Dr. Kent Brantley, a 33-year-old American incredibly sick with Ebola in Liberia, was treated with the blood of a 14-year-old patient of his who had survived the disease. Brantley, in the final stages of the diseases when he was given the blood, survived. According to those who witnessed the transfusion, the effects of the antibodies were seemingly evident within hours. But owing to another experimental vaccine he received, its impossible to say whether the blood is what saved him.

The only existing study, printed in the Journal of Infectious Diseases in 1999, leaves scientists with the same questions. It was conducted in June 1995 on eight patients suffering from from Ebola in Kikwit, Democratic Republic of the Congo. According to the doctors, all of the patients were “seriously ill with severe asthenia,” half of them hemorrhaging and two who eventually became comatose. After receiving transfusions of blood from those who had survived the disease, all but one survived. But in the process of getting the transfusions, the eight patients reportedly received “better care” than others, which made scientist unable to claim the blood as solely responsible for the recovery. “Plans should be made to prepare for a more thorough evaluation of passive immune therapy during a new [Ebola] outbreak,” reads the end of the study’s 1995 abstract.

Now, armed with $13.9 million, the original scientists at Institute of Tropical Medicine are teaming up with others to do just that.

Dr. Bob Colebunders, one of the authors of the 1995 study, had just found out about the grant when we speak. “We were never sure that it was the antibodies or the blood itself or the better care,” says the doctor, who also carried out extensive AIDS research in the Congo. “Now we can set up a scientifically well prepared study to evaluate the transfusions vs. improved care.” Led by Johan van Griensven, the study will commence in Guinea in the next three weeks.

After following the epidemic closely from his native Belgium, Colebunders is extremely hopeful that the answer will be the blood. He recalls how surprised he—and the rest of the scientists—were to hear that Ebola sufferers may benefit from the blood of survivors. “It was the Congolese doctors who decided to do it. In the initial phase, it was impossible to do; no one wanted to try it. But at the end of the epidemic there was a nurse in the team who became infected and surviving health care workers, they said let’s do it,” Colebunders remembers. “Even the American colleagues on site, they didn't believe it was going to work and they were reluctant,” he says.

According to doctors at the forefront of the fight today, they still are.

Dr. James Landmark, an expert pathologist and director of Clinical Laboratory Support Services at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha, participated in the blood transfusions of Dr. Kent Brantly. Or, as he’s quick to correct, “convalescent plasma transfusions.” While whole blood transfusions have been used to treat Ebola victims elsewhere, the transfusions in the U.S. involved plasma, the “non-cellular fluid” in which blood cells are suspended. “It’s the plasma that contains antibodies against Ebola virus in people who have survived the infection,” Landmark says in an email.

While there is not a specific study on the effectiveness in treating the Ebola virus with a convalescent plasma transfusion, the method of using antibodies to stave off infection in the body is well studied. “An everyday example would be the use of gamma globulin shots to passively immunize people following exposure to hepatitis A, or use of hepatitis B immunoglobulin following exposure to hepatitis B,” says Landmark.

The transfusions are not a cure, but are a second line of defense for the body. By bringing in anti-bodies, they can “modulate the severity” of the viral load in the victim’s blood, giving them the opportunity to produce antibodies on their own.

Of course, as Landmark notes, the procedure is not without risk. “Allergic reactions can occur, ranging from itching and rashes to life-threatening anaphylaxis. Plasma can transmit infection: Hepatitis B, hepatitis C, HIV and other viruses for example,” says Landmark. It is impossible to know when allergic reactions occur, and most that do are quite serious. Still, given the lethal nature of Ebola, many believe the potential benefits far outweigh the risk.

Despite the positive news, Landmark doesn’t view it as a solution. “Convalescent blood transfusions and plasma transfusions may help people who are sick survive the infection,” he says. “It won’t prevent the disease.” Turning the tide of the epidemic, he says, will require “rigorous contact, tracing, and quarantining.” Unfortunately, West Africa lacks many of the things required to make this happen.