President Donald Trump acknowledged on Monday night that the new Afghanistan strategy he unveiled is a reversal of his long-held objection to the very idea of having a U.S. military presence in the country.

But in announcing a ramp up of U.S. forces with no defined timeline for their departure, Trump tailored and mangled and obscured the policy to such a degree so as to make it both difficult to understand and—he hopes—palatable to his base. At one point, he asserted that his strategy was to have no publicly-stated strategy at all.

“We will not talk about numbers of troops or our plans for further military activities,” Trump told a crowd of servicemen at Virginia’s Fort Myer on Monday.

Presidents have made abrupt foreign policy reversals before, often breaking with campaign pledges when presented with a new set of geopolitical realities. Trump’s reversal stands out not just for the outright vehemence with which he previously argued that America needed to put an end to its 16-year-long war—Trump has called for total US withdrawal from Afghanistan and for handing the country over to an army of mercenaries—but also because of what it says about his foreign policy at large. In the seven months since taking office, Trump has expanded military operations in Yemen, Syria, Iraq, Somalia, Libya and, now, Afghanistan. And that’s in addition to an escalated nuclear standoff with North Korea.

And so, when pitching the notion that the time had come to enlarge America’s military presence, the president used a variety of different selling points to re-frame the context. This was, he stressed, an agenda based on counter-terrorism principles and devoting American blood and treasure purely to the country’s first-order military interests.

"We are not nation-building again,” he said. “We are killing terrorists.”

It was “America First” rhetoric plastered atop a military-oriented interventionist policy. And it was done, ostensibly, to ensure that Trump’s base, disillusioned with decades of Republican-led foreign policy adventurism, heard someone who remained skeptical.

Alas, many didn’t.

“Why did we even have an election?” wondered Mike Cernovich, a popular far-right internet media personality generally supportive of Trump. He mockingly tweeted a photo of a flak jacket-clad Jared Kushner, the president’s senior adviser and son-in-law, during a trip to Afghanistan this year, with the caption “General Jared.” In another tweet, he wrote, “Congratulations to President McMaster!” a derisive reference to White House National Security Adviser H.R. McMaster, who pressed the president to boost troop levels in Afghanistan.

The pushback that came after Trump’s speech was apparent in the process leading up to it as well. Inside the White House, the draw-down and ramp-up camps battled over the president’s plan, in an internal debate that contributed to the departure last week of White House chief strategist Steve Bannon, the West Wing’s most vocal critic of escalation in Afghanistan.

Bannon returned to Breitbart News, the prominent right-wing website that has favorably covered Trump for years. And in the run-up to Trump’s speech on Monday evening, as details of the troop surge announcement trickled out, Breitbart’s coverage ranged from skeptical to hostile. “America First? With Steve Bannon Out, Globalists Push For More War Abroad” read one headline.

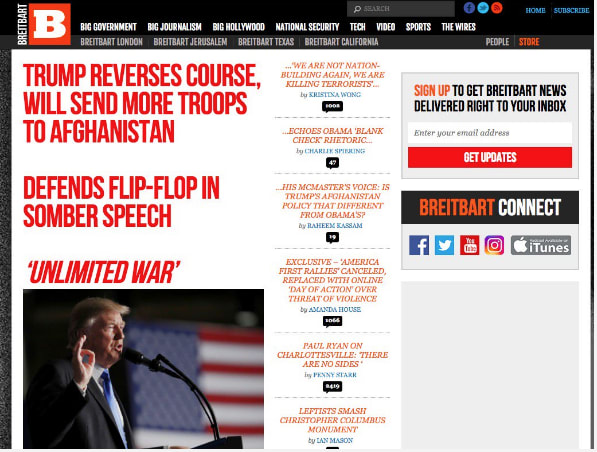

After Trump’s speech concluded, the lead story on Breitbart’s homepage braced readers for “UNLIMITED WAR.” (The site later took that headline down).

Bannon, Cernovich, and other elements of Trump’s less interventionist political base hoped for foreign policy more in tune with the president’s pre-White House rhetoric, when he dubbed the war in Afghanistan “a total disaster” and “a complete waste” and repeatedly called on President Barack Obama to withdraw U.S. forces completely. Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY), one of the few elected Republicans to echo this hope, was critical of Trump even before he spoke.

"The mission in Afghanistan has lost its purpose and I think it is a terrible idea to send any more troops into that war,” Paul said in a statement.

In a rare bit of self-reflection, Trump explained that the reason he changed his tune on Afghanistan was precisely because of the weight of his office. “[A]ll my life I have heard decisions are much different when you sit behind the desk in the Oval Office,” he said. And he tried to couch the shift by repeatedly invoking the possibility of another attack homeland. Twice, Trump referenced the attacks from September 11, 2001. “A hasty withdrawal would create a vacuum that terrorists—including ISIS and Al Qaeda—would instantly fill,” he said.

But instead of placating his base, Trump ended up drawing plaudits from an unfamiliar crowd.

Sen. Marco Rubio, a GOP defense hawk and 2016 campaign rival, defended Trump’s apparent reversal. The president “has made a decision based on information now available to him in office & on advice of wide array of experts,” Rubio wrote on Twitter. Sen. John McCain (R-AZ), one of the more pro-interventionist voices in the GOP and someone who has repeatedly butted heads with Trump in recent weeks, called the new policy “a big step in the right direction.” Trump, he added, “is now moving us well beyond the prior administration's failed strategy of merely postponing defeat.”

And then there was Marc Thiessen, one of the more prominent neoconservatives in media and a former speechwriter to George W. Bush, a man whose foreign policy record Trump has called an unmitigated disaster. Reacting to Trump’s pledge that U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan be hinged on “conditions on the ground, not arbitrary timetables” Thiessen wrote: “How many times did I write that?”