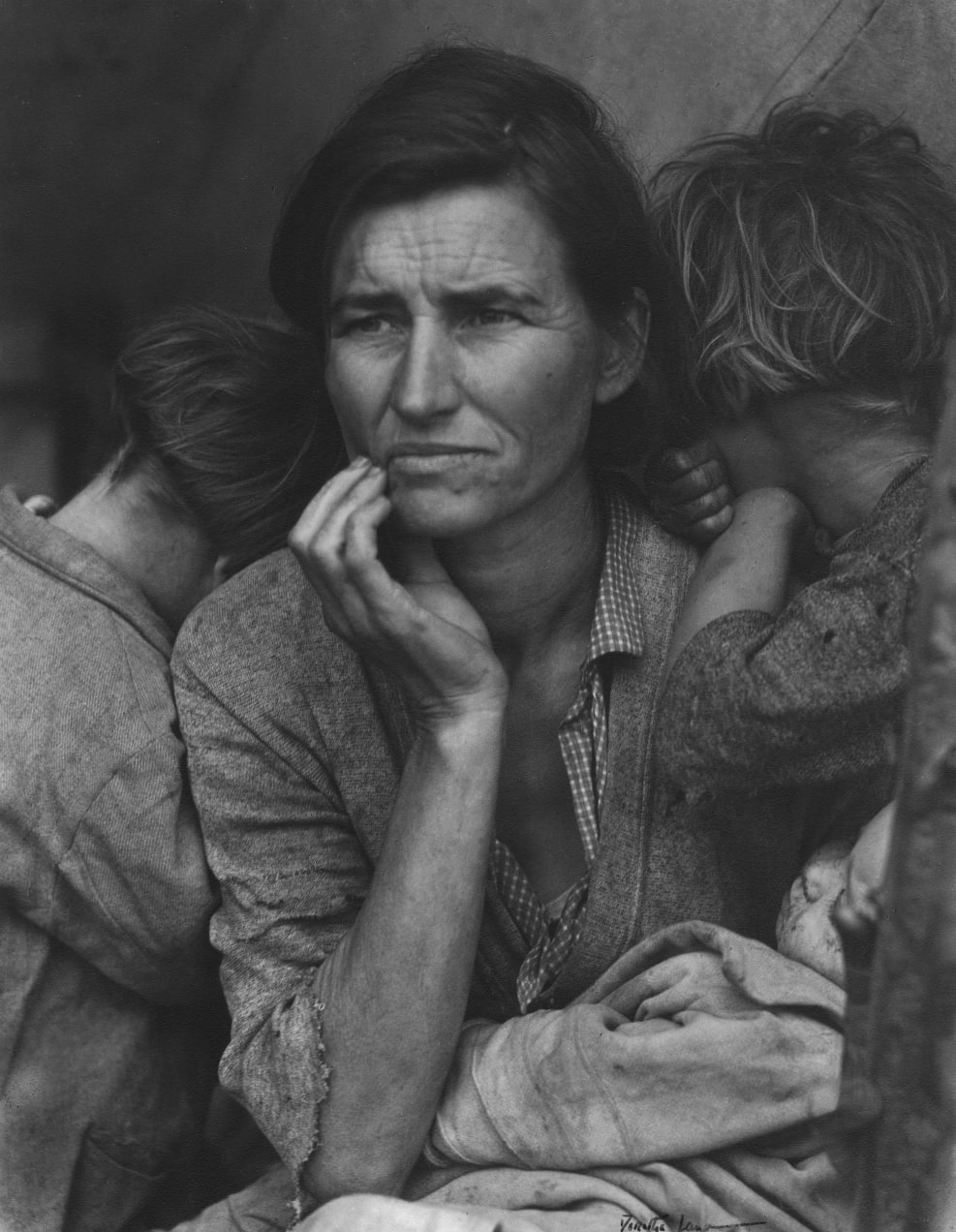

© The Dorothea Lange Collection, the Oakland Museum of California

1/13

Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California, 1936.

Staring at these images in Anne Whiston Spirn’s superb Daring to Look: Dorothea Lange’s Photographs & Reports From the Field, I began to wonder how much longer the word “documentary” will proceed the words “photographer Dorothea Lange”? Because the particulars of her subjects—the Okies, the sharecroppers, all the people who lived on the bottom rung of the Depression—matter to us less each year. The Depression is a thing we learn about in school, not something that many people alive experienced first hand. Fortunately, as the social urgency of her photographs becomes less urgent for us, the pure art of her pictures shines all the more intensely.

In the ’30s Lange worked for the New Deal’s Farm Security Administration, recording the lives of hard luck cases mostly on the West Coast and in the Piedmont South. It’s ridiculous to try to say who was best among that amazing crew of photographers with whom she worked, but she was as good as any of them, including Walker Evans.

She believed deeply in the work she did, and there is at least one concrete example proving that one of her pictures probably saved some lives. When “Migrant Mother” [above], her photograph of 32-year-old Florence Owens Thompson, was published in a San Francisco newspaper with the news that the Nipomo, CA encampment of out of work pea pickers in which Thompson was living was starving, the federal government rushed food to the frozen fields where the migrants were camped.

Lange insisted that she never “stole” a picture of someone. She always asked permission, and beyond that she always requested cooperation. She wanted the photograph to be a true collaboration between the photographer and her subject. I thought of that, too, while I was going through these images. I decided that it’s this collaborative spirit, every bit as much as her artistic and technical skills, that makes these photographs so vivid. It’s like the subjects are almost willing themselves through the lens, through the film. It’s like she’s a medium through which they can reach us. There’s something fierce and unnerving about Lange’s photographs, and something exalting, too.