CONCORD, New Hampshire—Standing in the back of the gymnasium at Concord's Rundlett Middle School, Heather Frye waited patiently to hear Elizabeth Warren speak. A native of nearby Bow, she was still surveying her options in the Democratic field, though she felt inclined to back the Massachusetts Democrat, whose combination of policy portfolio and personal biography reflected her own interests and life story.

Frye, who is in her early fifties, grew up in a single-parent home after her parents divorced. Her mom was thrust back into the workforce by necessity, and they struggled to buy food and pay for heat. Later in life, Frye herself got a taste of how difficult it can be for a woman in the workplace and what good can come when principled stands are made. When she applied for a role in a department store and was offered a job that paid comparatively less than her male colleagues, she decided to say no.

“Suddenly,” she recalled, “they came up with the money. Funny how that happens.”

For someone with that life experience, Warren’s story has resonance. “You do have to persist,” she explained, referencing the now-famous tagline that the senator has adopted for her campaign. “You do have to show grit. You do have to show perseverance.”

And yet Frye has an acute fear about making Warren the Democratic Party’s presidential nominee: Would her gender, though personally inspiring, be politically problematic?

“I struggle with that,” said Frye, donning a fleece vest, her cheeks still tinged red from the cold outside. “I wonder if the country is ready for a woman president.”

Warren is wondering too.

As the senator seeks to pull off a surprise New Hampshire win, her campaign is being hampered, ever so slightly, by a quintessentially Democratic paranoia: a stubbornly persistent belief that Hillary Clinton’s loss in 2016 is proof that misogyny remains a latent but potent force in American politics and that, in an election all about beating Donald Trump, resurfacing that might not be worth the risk.

“This is a backwards country in that regard. I approach life assuming I have equal rights. But I know it’s not always true. I know it’s not because of history. This is, in many ways, even stickier than gay rights because there are women themselves who are worried about women,” said Anne Dowling of Canterbury, New Hampshire. “I’m sick to my stomach over it. Of course, they should be comfortable with a woman. But I’m deeply worried about it.”

Faced with these fears, Warren has tried to thread a needle, emphasizing the historic nature of her quest for the presidency but often in subtle ways. On Sunday, her introductory speakers talked about the gender elements of the campaign. Rep. Katie Porter (D-CA) noted that Warren featured the “first all women co-chairs of a presidential campaign in the history of this country.” And Rep. Deb Haaland (D-NM) implicitly acknowledged the skepticism facing Warren when she instructed the crowd that, “If anybody tells you a woman can’t win, tell them to take a look at our class in Congress right now.”

On Saturday, Warren commemorated the three-year anniversary of the time Mitch McConnell admonished her for “persisting” on the Senate floor by reminding voters of institutional obstacles she often faces.

And when Warren herself took the stage on Sunday, it was once more to Dolly Parton’s “9-to-5”—an homage to working women that served as the main song on the feminist revenge fantasy film of the same name. But gender was not front and center in her speech, save for one or two references, including the time she was pushed out of the job because she was visibly pregnant. Instead, she spoke about her ability to unite the party and beat Trump.

Among Warren supporters—and some on the campaign as well—there is a belief that she gets none of the benefits for trying to break the last remaining glass ceiling in politics while getting all of the downsides that come with being a woman in politics. The sources of the gripes are numerous, including the fact that Warren was pressured into introducing a detailed plan for how she’d finance her Medicare for All proposal while Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) has not introduced any such equivalent proposal. Questions about her “electability” have dogged her more than former Mayor Pete Buttigieg, despite him hailing from a much smaller political perch and facing his own societal barriers. When she and Sanders had a dispute over whether he told her he believed a woman could not win the presidency only one person—Warren—was dubbed a traitorous snake online. And during Friday night’s debate, she got comparatively little speaking time next to her male counterparts, even though she had a strong showing in Iowa days before.

“Look at the coverage after Iowa. She finished third and the media just dismissed it,” said Mary, a New Hampshire native who declined to reveal her last name. “Look at Bernie! Can you imagine a woman of his age who had a heart attack? They’d be told to go home.”

Warren, for her part, never complains about this. Doing so would be against her political brand, which is heavy these days on her pitch that she is a unity candidate in a splintered Democratic field. But more to the point, to complain would be to invite its own set of gendered criticisms, and what’s the point of enduring that?

For the women in her crowd, it felt all too familiar.

“We have gone through it in our professional lives as attorneys,” said Lauren Noether, who hails from the Concord area. “You have to persist. You have to be dogged. You have to work in the background while your male colleagues get the attention. I saw it happen. I felt it happen too.”

But if Warren isn’t leaning on her gender as she makes her pitch to voters, those voters seem fine considering other aspects of her biography. Off to the side of her event, five students from New York University law school stood in a circle holding campaign signs. They had come to canvass for her in New Hampshire and when asked why, they went through a laundry list of reasons: her child care policy, her brain power, the fact that former HUD Secretary Julian Castro had endorsed her. All of them women, not one listed gender as a reason for their support.

Sam Stein/The Daily Beast

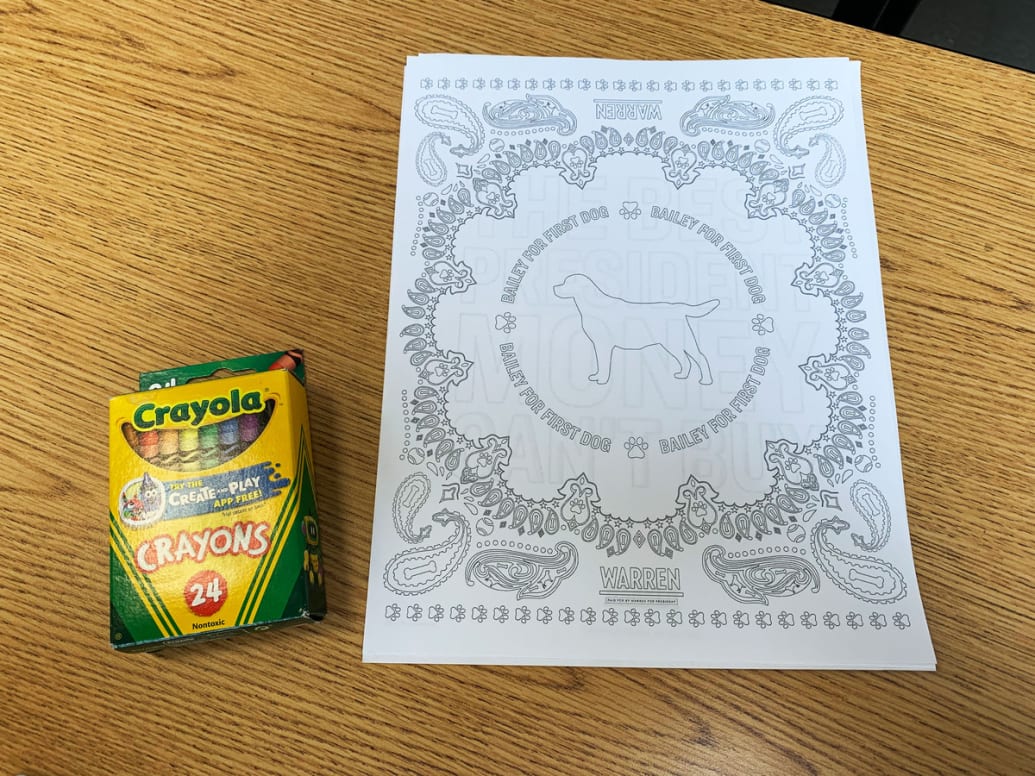

As Warren spoke, a group of young mothers stood along the folded bleachers, their children—all daughters—perched on their shoulders or crawling on the floor around their legs. The campaign has become so accommodating of kids that they’ve begun distributing crayons and color-in pages of Warren’s dog Bailey to serve as youthful distractions (though the piercing cry of a bored child often punctured the candidate’s stump speech). It seemed only logical that the young mothers were bringing their young daughters there to be part of a moment of symbolic female empowerment. And to a certain degree, they had. Warren was a draw, not because of her gender, however, but because, they believed, she could win.

Sam Stein/The Daily Beast

“I want the best candidate whether it is a man or woman,” said Karen Craver, of Concord. “And by best candidate, I mean the best to beat Trump.”