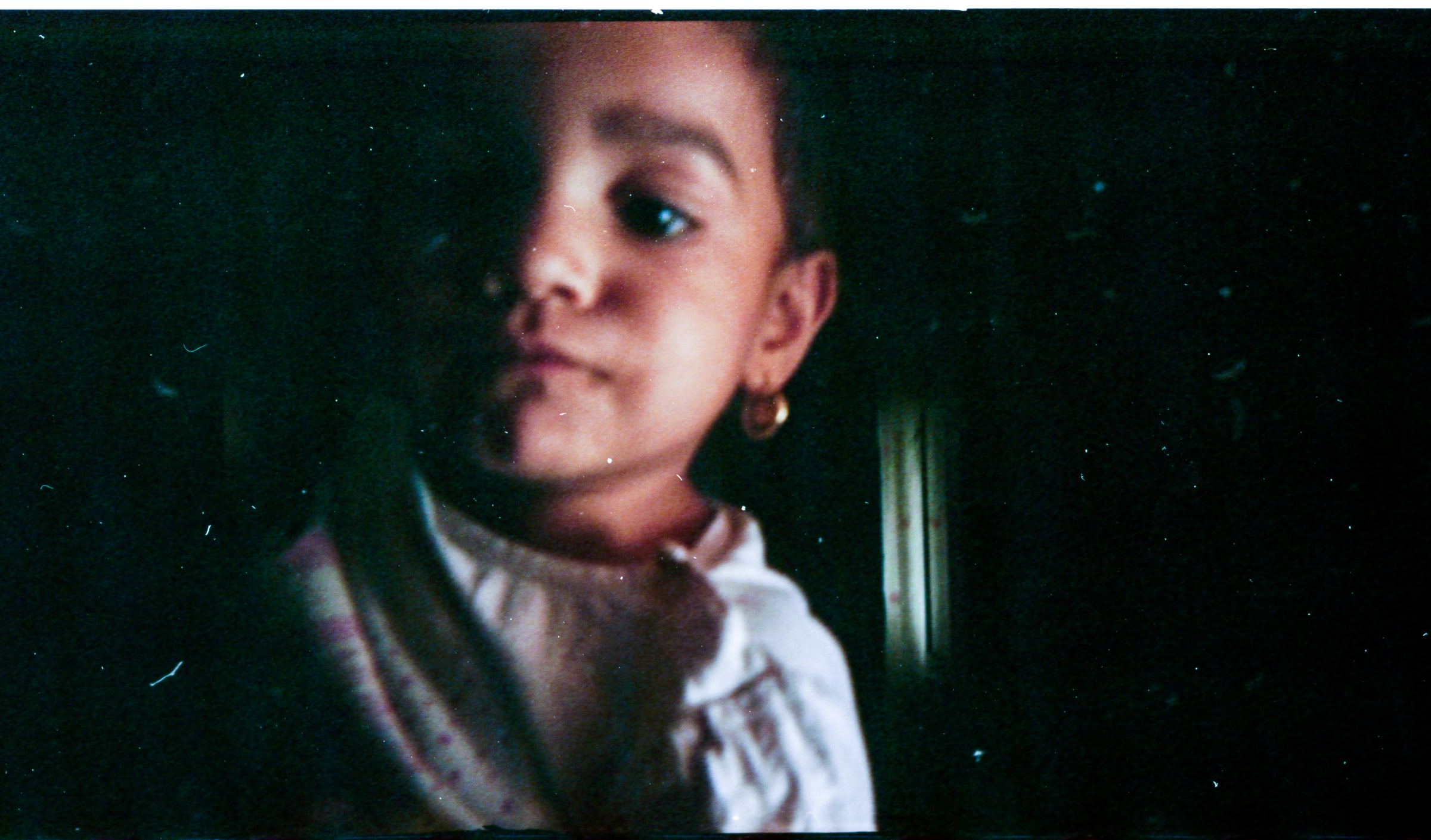

Life in Europe’s Largest Shanty Town, the Cañada Real—as Photographed by Its Children

Photos Courtesy Children Residents of Cañada Real

In a special project, children in Europe’s largest shanty town, the Cañada Real in Spain, were given cameras to photograph their lives. The results are shocking—and beautiful.

Carlos Gutierrez was “excited and nervous” about what he would see as he developed the films taken by children living in Europe’s largest shanty town, the Cañada Real.

Last summer, 39 children were given disposable cameras and asked to document their lives. What emerged in the darkroom was something very special: “I found the real Cañada Real,” said Gutierrez, smiling like he’d discovered a hidden world—which he had.

Courtesy Carlos Gutiérrez

The Cañada Real (loosely translated as “Royal Cattle Trail”) is an unofficial 16 km linear settlement outside Madrid dating back more than half a century. People have been moving to this ancient cattle trail for generations, building their own homes and raising families. The settlement winds its way around the outskirts of the city (parallel to the M-50 motorway) and is today home to around 7,300 people, a third of whom are children.

Courtesy Carlos Gutiérrez

Courtesy Carlos Gutiérrez

Seventeen nationalities live alongside one another in an assortment of self-built houses. Some are mansions several stories high and others are quaint Spanish bungalows shrouded in grapevines and succulents tumbling from windows. Other homes appear unfinished, with satellite dishes loosely placed on their roofs, and some have been bulldozed.

Courtesy Carlos Gutiérrez

Courtesy Carlos Gutiérrez

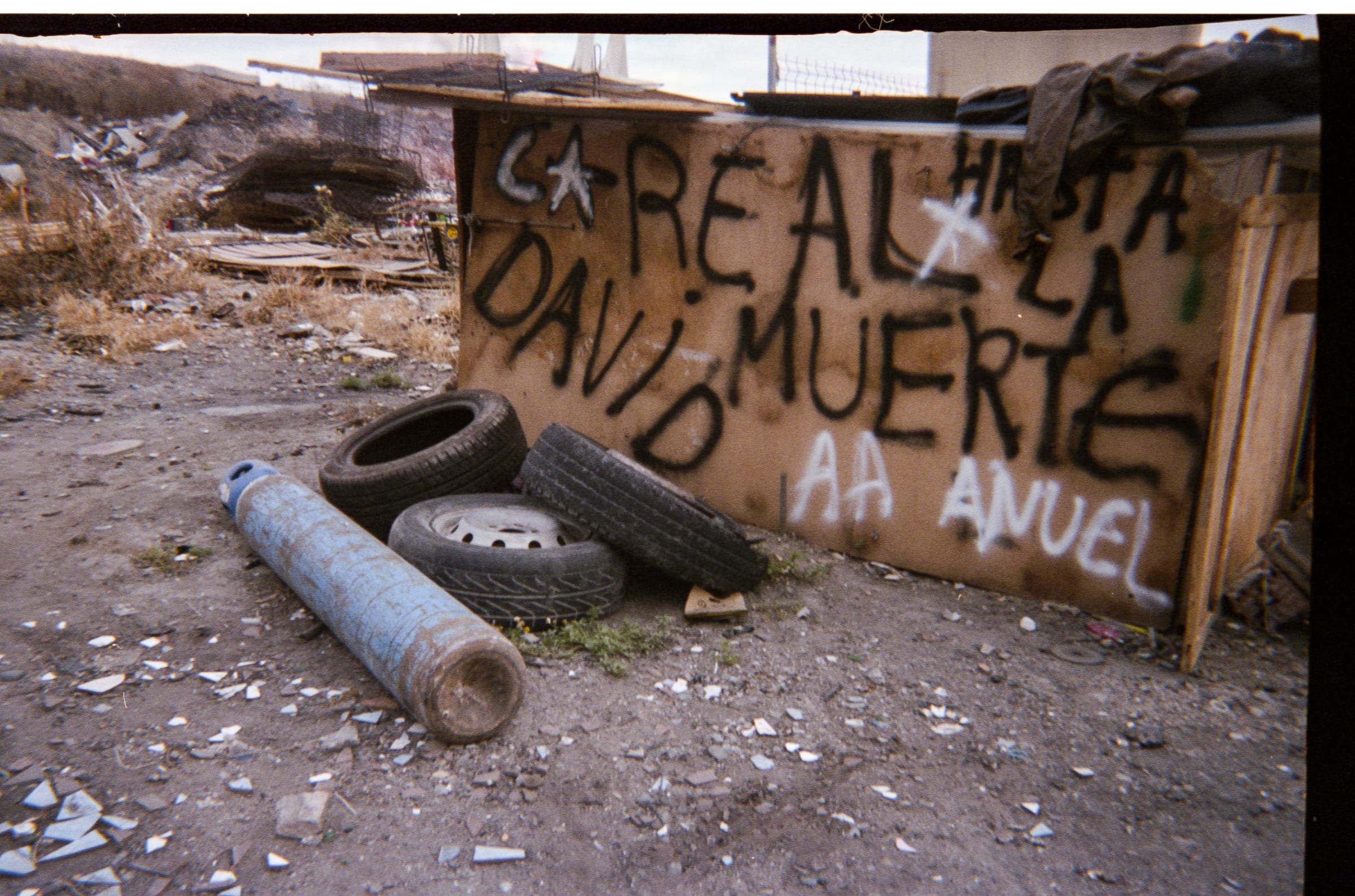

Sector 6 of the Cañada Real, where the photos for the project Mi Mirada—Cañada Real (“My Perspective—Cañada Real”) were taken, is home to 1,211 children. This 1.5 km stretch is the newest, largest, southernmost and poorest sector of Madrid’s shanty town, and part of it is also Spain’s most notorious drug-dealing area.

Courtesy Carlos Gutiérrez

Houses belonging to the Sector 6 drug dealers are routinely torn down. The debris that remains looks more like the path of a hurricane than the work of city-hall bulldozers. The leaving of rubble, broken furniture, and shattered glass is believed to be a hostile move to make it difficult for the residents to reconstruct a home in the same location.

Instead, they move a few meters forward and build shacks with chipboard and whatever structural elements they can reclaim from the rubble of their former home, patched together with plastic sheets.

Courtesy Carlos Gutiérrez

Courtesy Carlos Gutiérrez

Women dressed all in black clutching their children wave passers-by down in the hope that they’re here to buy drugs. On the other side of the street, women wearing niqabs and burkas are doing the school-run, the kids pulling tiny wheelie suitcases branded with their favorite cartoons and staying close to their mothers. When police cars whizz past, the children duck to the side of the road but seem unfazed by what they see. To them, this is normal.

Courtesy Carlos Gutiérrez

A few weeks ago, Philip Alston, UN Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights visited the Cañada Real and was shocked by the living conditions of Sector 6 residents.

Alston told El País, “I met people who live without clinics, without a job center, without schools and even without legal electricity, on an unpaved road next to incinerators in an area considered dangerous for human health.”

Courtesy Carlos Gutiérrez

Many residents want to leave, and although in 2017 the council promised to rehouse 150 families from Sector 6, only around 34 have been moved so far. Those that remain live in both hope and fear of moving; their living conditions will improve, but their community will be pulled apart.

Courtesy Carlos Gutiérrez

Growing up in the Cañada is something that will stay with these children well into their adult lives. Despite the fact that none of the children involved in Mi Mirada are from the drug-dealing area, the stigma of being from the Cañada Real is hard to shake off, even once they’ve left the settlement.

But this series of photographs hopes to shine an honest light on the lives of the people living here and prove, contrary to widespread opinion, that they are good, normal people who just want to live a normal and safe life.

Courtesy Carlos Gutiérrez

Courtesy Carlos Gutiérrez

“My father was a photographer, so I grew up surrounded by cameras,” explained Gutiérrez. “I watched him taking photos and developing the films, and when the photo emerged, it was like magic to me.” His aim was to share this magic with the kids of the Cañada, except this time the children would take the photos too, becoming the narrators of their own stories via the enchanting medium of photography.

Gutiérrez, in collaboration with Asociación Barró, a socio-educational association that works with marginalized communities, gave 39 children 20 cameras between them. He showed them how to hold the cameras and keep them safe, explaining that while capturing their day-to-day lives was an art project, it was also an opportunity for others to see their world through their eyes. “I could go with my camera and take photos of what I think is the real Cañada, but I will never see it the way that they see it,” said Gutiérrez.

Courtesy Carlos Gutiérrez

Courtesy Carlos Gutiérrez

A month passed and it was time to collect the cameras. Gutiérrez was surprised to receive almost all of them back: 19 out of 20. “Often, when we give them materials, they disappear—perhaps they’re sold. But with the cameras, it wasn’t like this. They were very motivated and excited to give the cameras back.”

Gutiérrez began developing the films one by one, with the images magically appearing before his eyes. “There were pigs and snakes inside houses! But also lots of shots of skies, landscapes, and their friends.”

Courtesy Carlos Gutiérrez

Courtesy Carlos Gutiérrez

Every single photo is peaceful, colorful, and exotic—like paradise. But looking past the bright blue skies and the stark, narrow shadows, you can really feel the heat of the sun; last summer was the hottest on record in Madrid, and people living in Sector 6 of the Cañada are exposed to all the elements.

These photos show us that life in the Cañada is tough: Many houses have no running water, electricity or even bin collections, but this is normal. The harsh landscape, makeshift housing, and burning rubbish—again, this is life in the Cañada.

“We decided to have at least one photo from each camera, and the kids and their families chose them. Photos that we didn’t choose included cannabis plants, police, and naked siblings,” says Gutiérrez. “They don’t understand social norms. They’re free and they don’t care—far more than we ever could as adults.”

Courtesy Carlos Gutiérrez

Their view of their world is honest and uncontaminated by rules or filters. For the first time, we can see an alternative perspective on the Cañada.

Journalists have been covering the struggle of the Cañada’s residents for decades, but stories of drug-dealing, poverty and fear have only sensationalized this forgotten neighborhood of Madrid. That’s not the real Cañada Real. This is.