On Thursday, the CIA declassified hundreds of files from its in-house journal, Studies in Intelligence, after a successful Freedom of Information Act request from a former employee, resulting in a bonanza of fascinating and downright weird tales from the history of the CIA from the 1970s through the 2000s. Among the hundreds of files, available here, we found this intriguing tale of Nazi plans to destabilize the American and British economies in the final days of the Third Reich.

In November 2000, CBS television broadcast to the world its efforts to locate hidden Nazi treasures in the deep waters of Like Toplitz in the Totes Gebirge mountains of western Austria. During the previous summer, Oceaneering Technologies—the same underwater salvage company that discovered the Titanic—had mapped the lake and used a sophisticated one-man submarine to scour its freezing, dark bottom. Only at the end of the search did Oceaneering detect the remnants of wooden crates, which turned out to contain counterfeit British pounds and American dollars. The bills were in excellent condition. The lake—which has no oxygen below 65 feet—“preserves everything” that falls into it, according to a local resident. Although more valuable treasures did not emerge from Lake Toplitz during the expedition in 2000, the discovery of the forged currency reawakened interest in one of the most bizarre intelligence adventures from the climactic end of World War II.

Operation Bernhard

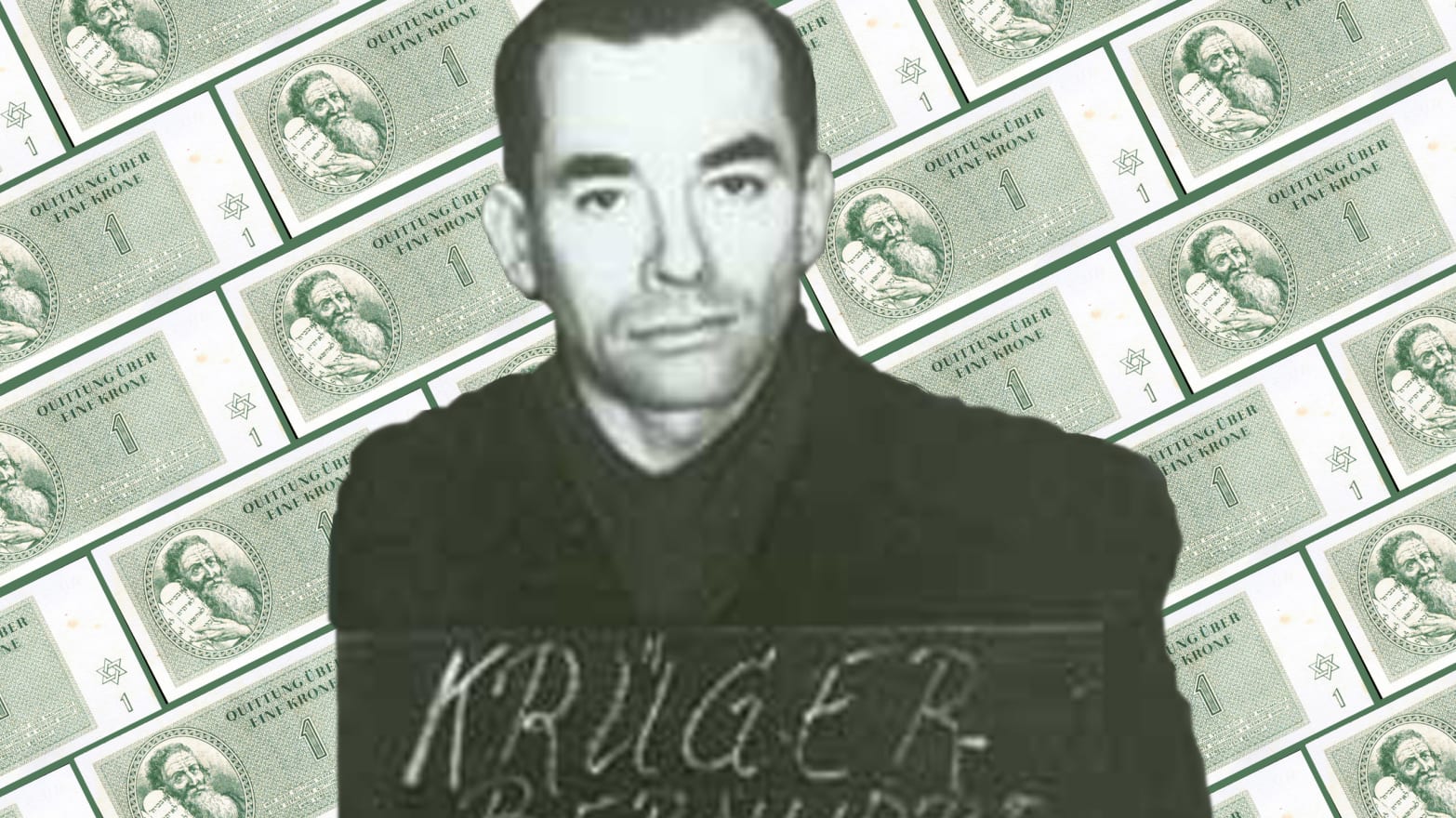

By 1939, the German Reich had begun to formulate a plan to undermine the economies of the British Empire and the United States through currency destabilization. Known as Operation Bernhard, the plot was launched by SS officers Alfred Naujocks and Bernhard Kruger of the Reichsicherheitshauptamt (the German Security Main Office, or RHSA), who decided to produce bogus currency in addition to false documents, as part of a broad wartime intelligence campaign. The German counterfeiting scheme ranks among the war’s most interesting clandestine activities and involved the highest officials in the Third Reich. “Had this counterfeiting operation [been] fully organized in 1939 and early 1940,” Holocaust scholar Rabbi Marvin Hier has commented, the “results of World War II may have been quite different.”

As it turned out, it took the Germans until 1942 to put Operation Bernhard into high gear. At Sachsenhausen concentration camp near Berlin, SS Sturmbannfuhrer Bernhard Kruger, oversaw the work of 140 Jewish prisoners trained as forgers. Isolated from the main prison area by barbed wire fences, two barracks were set aside for inmates working as printers, binders, photographers, and engravers. The Nazis placed a prisoner as the head of each section under the overall charge of Oskar Stein, an office manager and bookkeeper. In addition to sparing their lives, Kruger offered the prisoners better food and other privileges for their hard work.

The Germans faced numerous technical difficulties in counterfeiting British and American money. By mid-1943, the SS had contracted with the Hahnemuhle paper factory in Braunschweig in northern Germany to make the special rag needed to replicate British money. The Germans used ink produced by two companies in Berlin. Wartime shortages, coupled with imperfections, limited the production of British currency. The Germans reportedly printed some 134 million pounds sterling in less than two years, yet Stein estimated that only 10 percent of it could be considered usable. Efforts to reproduce American currency proved less successful, despite the work of Solly Smolianoff, an experienced criminal forger whom Kruger added to his collection of skilled workers at Sachsenhausern.

In addition to British and American currency, the SS crafted a wide array of forged civilian and military identity cards, passports, marriage and birth certificates, stamps, and other official documents. Reichsfuhrer Heinrith Himmler reportedly planned to use these forged documents and money to create havoc among the Allies as well as to underwrite Nazi agents throughout the world. Himmler, for example, wanted to drop the imperfect British pounds on the United Kingdom by airplane. These notes were good enough to fool anyone but an expert,” a postwar report noted. “Therefore, if a large quantity was dumped and the English government declared them counterfeit, many would say the government was merely trying to avoid redeeming them.”

The rapid advance of the Soviet army in early 1945 necessitated the evacuation of the Jewish counterfeiters from Sachsenhausen and their transfer to Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria. In mid-April, the Germans again moved the prisoners and machinery to an unused brewery at Redl-Zipf where they hoped to start up production in an underground factory in the mountains. The Nazis had little time to resume counterfeiting before the war came to an end. By the last week of April, the Germans had ordered the inmates to destroy as much of the machinery and the money, and as many of the records as possible. In one of the last desperate acts of World War II, the SS dumped crates full of counterfeit money into nearby Lake Toplitz. They then moved the inmates to Ebensee concentration camp. The US Army’s liberation of the camp on 6 May prevented the Germans from killing the inmates. Once freed, Operation Bernhard’s workers quickly scattered.

Fears of “The Nazi Redoubt”

In 1945, the US Army and the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) raced to investigate rumors of a Nazi counterfeiting operation, fearful that such resources might be used to finance an underground Nazi resistance movement. Worries about a last ditch Nazi stand in the Alps had mounted appreciably over the final year of the war. Even as German forces melted and Allied armies swarmed through the shell of the Thousand Year Reich in the spring of 1945, Gen. Dwight Eisenhower noted that “If the German was permitted to establish [a] Redoubt, he might possibly force us to engage in a long, drawn-out guerrilla type of warfare, or a costly siege.”

As the noose tightened around the Third Reich, the OSS began to glean bits of information about an intricate German plot to manipulate currencies. In March 1945, the OSS in Bern learned that the former chauffeur of the Hungarian ambassador to Switzerland had come across a “Herr Schwendt” while traveling through Merano, northern Italy. This “Schwendt” had urged the Hungarian to get a job in the American or British legations in Switzerland and provide information to the Germans in return for dollars and pounds to sell on the Swiss black market. Instead, the chauffeur contacted the OSS. He said that “Schwendt” lived at Schloss Labers on the outskirts of Merano and that his castle had a radio station and extensive telephone installations. He also reported that he happened to see that “cases full of brand new Italian Lire were being unpacked.” The OSS reported Schloss Labers as a bombing target.

In April, a German deserter told the OSS in Switzerland that Himmler had formed “Sonderkommando Schwendt” as an independent unit “to purchase abroad a variety of objects including gold, diamonds, securities, as well as certain raw materials and finished products.” Two weeks after VE-Day in May, the OSS intercepted a letter in Switzerland from what appeared to be a German civilian who had been involved in obtaining the right paper stock for the printing of British currency. The letter-writer provided an account of the beginnings of the operation, the firms involved, and the names of several SS officers who had supervised the production. The author had even visited the production facility and met the Jewish inmates.

Military Investigation

In early May 1945, US Army Capt. George J. McNally, Jr., received word that US troops in Bavaria had located a factory stocked with boxes of counterfeit British pounds. McNally was assigned to the Currency Section of the G-5 Division’s Financial Branch at Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force, in newly captured Frankfurt. A former Secret Service agent who had specialized in counterfeiting cases before the war, he soon found his peacetime skills in demand in occupied Europe. McNally heard that American soldiers and Austrian civilians were busily fishing out millions of dollars worth of British money found floating in the Enns River. Meanwhile, a German army captain in Austria had surrendered a truck with 23 boxes of British money, valued at 21 million pounds sterling. McNally spent the next eight months untangling the twisted webs of Operation Bernhard that extended into Austria, Czechoslovakia, Germany, and Luxembourg, seeking to uncover how the Germans had compromised the security of the monetary systems of the Allies.

In late May, McNally began coordinating his investigation into German currency operations with the British. From intelligence sources in the Middle East, the British already knew that the Germans had been busily undermining their currency. At a meeting with British officials in Frankfurt in early June 1945, McNally met P.J. Reeves, the manager of the St. Luke’s Printing Works in London (the British equivalent to the US Bureau of Printing and Engraving). Reeves was visibly perturbed when he saw the amount of British currency that McNally had recovered in Austria. “He began going from box to box, rifling the notes through his fingers. Finally he stopped and stared silently into space. Then for several seconds,” McNally later recalled, “he cursed, slowly and methodically in a cultured English voice, but with vehemence. ‘Sorry,’ he said at last. ‘But the people who made this stuff have cost us so much.’” Indeed, the Bank of England had to recall all of its five-pound notes and exchange them for new ones.

McNally, joined by Chief Inspector William Rudkin, Inspector Reginald Minter, and Detective Sgt. Frederick Chadbourn from Scotland Yard, and Capt. S.G. Michel, a French army liaison officer attached to the Americans, focused on interviewing Germans involved in planning Operation Bernhard and the concentration camp inmates who produced the fake money. Throughout the summer and fall of 1945, they crisscrossed Europe to interrogate witnesses, including Obersturmbannfuhrer Josef Spacil, Kruger’s commanding officer at Sachsenhausen. McNally also tried to raise the crates of money that the Germans had reportedly dumped into Lake Toplitz, but a special team of US Navy divers found nothing.

Drawing on support from the US Army’s Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC), the OSS, and the US Navy, McNally wrapped up his investigation by early 1946 and completed an extensive report on the history of Operation Bernhard and the known disposition of the false currency. “Thus,” he wrote, “in disorganization, flight and destruction, ended the most elaborate and far reaching scheme that an invading army ever devised for the wholesale counterfeiting of the money and credentials of other countries.”” The US military returned the counterfeit British currency to the Bank of England and closed its file on Operation Bernhard. Only small amounts of forged American money were ever found. As far as the American military was concerned, Nazi Germany’s counterfeiting activity became a curious footnote in the annals of the war.

OSS Seeks the Kingpins

As the war closed, the OSS, too, set out to locate members of Operation Bernhard who could pinpoint hidden Nazi wealth before it could be used to finance underground resistance efforts. Working at the same time as, and on occasion in coordination with, the McNally team, OSS/X-2 (counterintelligence) already had several hot leads by mid-May 1945. 1st Lt. Alex Moore, an OSS officer assigned to the Sixth Army Group’s Special Counter Intelligence (SCI) detachment, was the first OSS officer assigned to the counterfeiting case. He took Karl Friedmann, a captured SS officer and member of Operation Bernhard, to Rosenheim near Munich to pick up George Spitz, a 52-year old Austrian Jew whom Friedmann had fingered. A prewar art dealer who had lived in the United States as a youth, Spitz was identified as one of the distributors of the counterfeit funds. Spitz admitted to Moore that he had worked for the Germans, but claimed that it was under duress because he feared arrest by the Nazis.

Spitz soon provided extensive leads into the Nazi campaign to undermine the Allies’ monetary systems. He recounted to Moore how he had escaped from the Nazis and then obtained fake documents from a corrupt SS officer, Josef Dauser and his secretary, Bertha von Ehrenstein, who worked for the Nazi foreign intelligence service in Munich. Spitz claimed to have met a German named. Wendig in Munich in 1943, who asked him to travel to Belgium to purchase gold, jewelry, and pictures. Spitz made six trips and exchanged some 600,000 marks worth of counterfeit English pounds. Moore interrogated both Dauser and his secretary to check Spitz’s account.

Moore’s investigation continued to bring out new details of the Nazi counterfeiting operation. By the end of May, the OSS officer had pinpointed Friedrich Schwend (sometimes spelled Schwendt) as Operation Bernhard’s pointman for the distribution of bogus money and identified his various cover names, including Dr. Wendig and Fritz Klemp. According to OSS sources, Schwend had worked from Schloss Labers in northern Italy — the same location reported by the Hungarian chauffeur—and used couriers to sow counterfeit money throughout Europe. Although not a member of the SS, he took the rank and identity of SS Sturmbannfuhrer Dr. Wendig who had died in an Italian partisan attack in 1944. Schwend’s castle was guarded by a detail of Waffen SS soldiers and identified as Sonderstab-Generalkommando III Germanisches Panzerkorps, the Special Staff of the Headquarters of the Third German Armored Corps.

Schwend apparently retained one-third of the profits derived from the sale of the counterfeit money. He and his underlings used the fake currency to purchase luxury items on the black market as well as to buy weapons from Yugoslav partisans anxious to make money from the arms provided by the British and Americans. The Germans, in turn, sold the Allied equipment to pro-Nazi groups in the Balkans. Money distributed by Schwend also went to pay German agents abroad — Elyesa Bazna, a famous German agent in Turkey known as CICERO, was paid in false British currency produced by Operation Bernhard.

Schwend’s job was not without risks. The Gestapo was on the lookout for counterfeiters and black marketers and sometimes apprehended Schwend’s men by accident. Rivalries among senior German SS officers, including Himmler, Reinhard Heydrich (first head of the RSHA), Heinz Jost (first head of RSHA’s foreign intelligence section), Ernst Kaftenbrunner (Heydrich’s successor as RSHA chief), Heinrich Mueller (head of the Gestapo), Otto Ohlendorf (head of another RSHA section), and Walter Schellenberg (Jost’s successor in the foreign intelligence section), impacted on many aspects of Operation Bernhard. Mainstream German bureaucracies, including the Foreign Ministry and Reichsbank, vehemently opposed any tinkering with the monetary systems, even those of the enemy. As it turned out, German use of counterfeit pounds destabilized the already fragile economies of several friendly countries, Italy in particular.

As the OSS pieced together the Operation Bernhard network, it made plans to apprehend those participants not already in custody. On 18 May, Spitz led Moore to Prien, where they located a large collection of trunks and crates belonging to Schwend. Schwend, however, was nowhere to be found. Spitz also helped Moore collar persons on the Allies’ wanted list not associated with Operation Bernhard, including Heinrich Hoffmann, Hitler’s personal photographer, and Loomis Taylor, the American “Lord Hee Haw,” a Nazi collaborator close to Hitler.

On 10 June, the OSS reported that it had arrested Schwend and started to interrogate him to gain further details about what it called the “RSHA Financial Operation.” The Americans initially held Schwend at the Seventh Army Interrogation Center in Ludwigsburg. Describing Schwend as a “mechanical engineer,” the Center’s records note that he “bought machinery and tools for factories.” Whether the Army listed Schwend in this category out of ignorance or for other reasons is not known. Shortly afterward OSS officers removed Schwend from the Interrogation Center and placed him in Munich’s Stadelheim prison where he remained for three weeks before he relented and spoke to his captors.

Meanwhile, Moore had been transferred back to the United States and Capt. Charles Michaelis, an X-2 case officer for several OSS double agent operations in France during the war, began to handle Spitz and Schwend. Spitz impressed Michaelis as “reliable, trustworthy and intelligent… [and] willing to cooperate.” In an effort to get Schwend to talk, Michaelis took Spitz to Stadelhelm prison. Spitz “persuaded Schwend that his best chance would be to confess his activities with the RSHA and to cooperate with us.” The OSS judged that “Spitz is primarily responsible for the success of this mission.”

As an initial act of good faith, Schwend agreed to turn over to the OSS all of his “hidden valuables.” Michaelis and Capt. Eric Timm, the X-2 chief in Munich, accompanied Spitz and Schwend to a remote location in Austria in July 1945, where Schwend uncovered more than 7,000 pieces of French and Italian gold that he had buried only days before the end of the war. Michaelis reported that Schwend estimated that the gold, which weighed over 100 pounds, had a value of $200,000. Michaelis recognized that the “money constituted a possible threat to Allied security as it could have been used to finance anti-Allied activities.”

With one successful mission under its belt, the OSS began to use Schwend as a “bird dog” for other hidden assets. In late July, Timm and Michaelis took Schwend and Spitz to Merano to visit Schwend’s former headquarters. The Army’s Counter Intelligence Corps had already rounded up several of Schwend’s employees who had remained in Merano, but CIC reported that the detainees did not have a clear picture of the overall counterfeiting operation. Nonetheless, after, further interrogation of one of Schwend’s staff still in Merano, the OSS was able to recover nearly $200,000 worth of gold, American currency, and diamond rings.

By then, both Spitz and Schwend had clearly demonstrated their value to OSS. According to Michaelis, Schwend added to his laurels by writing a history of Operation Bernhard.

Shifting Gears

As tensions mounted between East and West during the early Cold War, American intelligence began to use several former members of Operation Bernhard as agents to collect information extending beyond their wartime activities. In August 1945, Timm reported that “it has been for sometime apparent that a well-balanced network of counter-intelligence and counter-espionage agents must include persons from all spheres of activity.” Timm observed that “the implementation of the penetration agent program wherein the use of former GIS [German Intelligence Service] personalities is contemplated remains of critical importance.” With an eye to a resurgent Nazi party, the Munich X-2 chief commented, “such persons are of importance because they are in a position to recognize other GIS personalities and are logical contacts for any illegal resistance group.”

To target the resurgent Nazi movement, X-2 recruited some 13 agents in Munich and had another dozen under consideration. Spitz and Schwend were among Timm’s stable of assets. Schwend, in turn, brought other Operation Bernhard associates on board, including George Srb, a Czech, and Guenther Wischmann, his “salesman” in Slovenia. Wischmann had been arrested in June 1945, but Michaelis was able to obtain his release from prison.

Timm used Spitz, codenamed TARBABY, in a variety of ways, although initially he was not tasked as a regular agent. In September 1945, Spitz supported an OSS effort to enlist released business and banking leaders to provide information on the financial aspects of illegal Nazi activities within postwar Germany. Timm felt that Spitz had “an encyclopedic knowledge of all figures of any importance in industry and economics throughout Europe.” The Munich X-2 chief recorded in late October 1945 that “TARBABY will prepare and submit regular semi-monthly reports on financial and economic matters, as well as other items of interest which he can obtain.” In this capacity, Spitz provided information on the German Red Cross and the Bavarian Separatist Movement in southern Germany.

By November 1945, Michaelis and Timm had been reassigned, leaving Sgt. Boleslav Holtsman as X-2’s lone representative in the Bavarian capital. Holtsman used Schwend to obtain a variety of reports on persons who “might be used by the American intelligence in some way.” Additionally, Schwend told Holtsman about the organization and structure of the Czech intelligence service and the exploitation of Jewish refugees by the Soviets. Holtsman was impressed with Schwend’s work in Munich and commented, “His knowledge of personalities and underground groups in Italy, Yugoslavia, and in Germany is very wide.” Perhaps reflective of his ability to get information, X-2 gave Schwend the codename FLUSH.

Balancing Ends and Means

Given their wartime affiliations and postwar opportunism, none of X-2’s assets had clean backgrounds. In the ruins of Europe, the agents’ access to sources and the pressing need for intelligence outweighed concerns about their tainted reputations.

Nonetheless, files continued to fill with damaging information as postwar debriefings proceeded. Walter Schellenberg, RSHA’s foreign intelligence chief, was among those who surrendered in 1945. Transferred to Great Britain for interrogation, he offered the Allies a window into German operations from the highest vantage point. Schellenberg told his captors about the intrigues that had riddled the intelligence and security organs of the Third Reich and filled in the gaps about Operation Bernhard, He claimed to have grown incensed at the latitude that Schwend enjoyed in dispensing false British currency and described him as “one of the greatest crooks and imposters.” Because Schwend marketed some of the false money in territories controlled by the Germans, Schellenberg said that the Reichsbank itself ended up buying some of the counterfeit currency.

Neither Schwend nor Spitz maintained a low profile in the ruins of Munich and they soon attracted attention. Spitz became a well-known figure in early postwar society circles. As X-2’s sole representative in Munich for most of the period between 1945 and 1947, Holtsman needed to maintain good relations with local officials. According to a 1947 report, he found Spitz’s parties to be an excellent way to meet the senior Americans in charge of the city’s military government. In turn, Holtsman assisted Spitz in obtaining a vehicle and supplies. Since Holtsman did not receive much guidance or support, he had to scrounge for supplies and ran his own operations.

It did not take long, however, for Spitz’s past to catch up with him. The Dutch representative at Munich’s Central Collecting Point — which handled art recovered from the Nazis—listed several pieces of art and rugs that Spitz had sold to Schwend during the war. In November 1946, Edwin Rae, the chief of the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives Section of the military government in Bavaria requested that US authorities in Italy assist in tracking down looted Dutch art in that country, to include a search of Schwend’s last-known location in northern Italy.

In October 1947, H.J. Stach, another Dutch investigator, questioned Spitz at his house in Munich about his activities in Holland during the war. According to Stach, Spitz “became furious” and demanded to know why he was being sought after, when he was a Jew who had been in the “underground.” Spitz produced a September 1945 letter of reference from X-2’s Capt. Timm and also told the investigator to check with Holtsman. Stach, however, continued to distrust Spitz and commented, “It is of great importance that this case should be handled very carefully. Spitz is one of the greatest swindlers.” In January 1948, Spitz again fell under suspicion for his role in the looting of art in Europe during the war. Then, a year later, he drew high-level attention because of allegations that he worked in the Munich black market with August Lenz, a banker and former OSS agent.

Finally, in the spring of 1947, Holtsman dropped Spitz as an agent, terming him a security risk. Two years later, the CIA tersely summed up the reasons in a cable: “[Spitz’s] activities Holland and Belgium during war never satisfactorily clarified… Services both Spitz and Lenz minimal and reports praising their services need grain of salt. Both believed [to be] opportunists who made most [of] connections with American officials to further personal positions, which [were] quite precarious [in] early clays [of] occupation since it [was] known that Spitz particularly had served as agent for SD [foreign intelligence service] and possibly Gestapo.”

Schwend also attracted scrutiny. In February 1947, the Central Intelligence Group in Rome reported that US military counterintelligence personnel and the Italian, police had raided a number of buildings in Merano in 1946, including Schwend’s old headquarters at Schloss Labers. The raid netted large quantities of counterfeit pound notes, which led the Americans to believe that the Germans had a plant still producing counterfeit dollars and pounds as well as US military occupation script

In 1947, Schwend’s situation became more precarious when it was discovered that he had defrauded what appears to have been the Gehlen Organization, the nascent West German intelligence service, then under US Army sponsorship. In early 1947, Holtsman attended a party in Munich where Schwend announced that he would soon take a trip “to visit his family in Italy.” From there, he fled to South America. He later wrote two letters to Holtsman from abroad, noting that he would “always remember the Americans for the kind treatment he received.” Using the name of Wenceslau Turi, a Yugoslavian agricultural technician, on a Red Cross passport issued in Rome, Schwend and his second wife arrived in Lima, Peru, after crossing the Bolivian border in April 1947. The new immigrants declared their intention to take up farming. In fact, Schwend went to work for Volkswagen in Lima and also served variously as an informant for several Peruvian intelligence and security services.

Schwend’s past caught up with him in South America. In early 1948, Louis Glavan, who had run Schwend’s affairs in Yugoslavia during the war, denounced him in a letter to Gen. Lucius Clay, the US military governor of Germany. Schwend had described Glavan in glowing terms to US intelligence in 1946, but, clearly, the two men had had a falling out. In Glavan’s letter to Clay—subsequently sent to the European Command’s Office of the Director for Intelligence and the CIA—he claimed that Schwend and his wife had moved to Lima using false identities and were living from proceeds derived from counterfeit RSHA funds. Furthermore, Glavan fingered Spitz as the individual who had persuaded the Americans not to investigate Schwend for his Nazi activities. After a preliminary investigation, the CIA concluded that the allegation “comes from a person who… may possibly be denouncing Schwend for personal or business reasons. Thus, the reliability of that information should not be taken at its face value until confirmed by other sources.” The Agency told the Army in January 1948 that it had no contact with Schwend and had nothing to do with his immigration to South America.

Years later

In the 1960s, reports of Schwend’s counterfeiting activities, drug smuggling, and arms dealings throughout Latin America attracted the attention of the CIA, the US Army, the US Secret Service, the British Intelligence Service, and the West German Federal Intelligence Service. A West German informant in Algiers in 1966, for example, claimed to be able to provide fresh samples of bogus dollars produced by Schwend in exchange for “financial help.” The CIA directed a source in the Peruvian Investigations Police to pursue the lead. Schwend denied any current counterfeiting activity, but divulged his wartime role to the Peruvians. When pressed, he continued to deny knowing where the plates for the British counterfeit pounds from Operation Bernhard were buried, although he said he suspected that they might still be located with a cache of RSHA chief Kaltenbrunner’s papers near Lake Toplitz in Austria.

In 1969, a trace done by the US Army turned up a 10-year-old report on Schwend in which the German claimed to have written “various American authorities charging that, during confinement by CIC in 1945, he was robbed of a considerable amount of money and. that much of his immediate personal property was confiscated and never returned.” Given the late date of Schwend’s allegations, the Army was unable to investigate and found nothing in its files to substantiate them.

In a bizarre epilogue to a bizarre life, the Peruvian government took Schwend into custody following the murder of a wealthy businessman in early 1972. Papers found in the victim’s possession revealed the extent to which Schwend had blackmailed Peruvian officials, traded national secrets, and broken currency laws. Although Schwend was initially released, his life began to unravel. A Peruvian court subsequently convicted him of smuggling $150,000 out of the country and he was given a two-year prison sentence. Then, in 1976, Peru deported Schwend to West Germany, where he landed in jail once again when he could not pay a $21 hotel bill. The German and Italian governments still held a warrant for Schwend’s arrest in connection with a wartime murder, but decided not to prosecute. Schwend was freed, but left homeless. He returned to Peru only to die in 1980.

Weighing Operational Decisions

Shortly after the war, the strategic Services Unit wrote a classified history of the OSS during World War II. The pursuit of the Operation Bernhard counterfeiters was fresh in the minds of the compilers who hailed it as a great success story for the OSS because it recovered large sums of money and other valuables. Yet for all of the positive attributes of that financial operation, the project clearly linked American intelligence with some unscrupulous characters. Useful to the Americans in 1945 as Europe lay in ruins and the Cold War loomed, Friedrich Schwend and George Spitz were among the most prominent of the agents-of-opportunity who—for decades after the war—profited from their association with the OSS. Their cases illustrate the perennial challenge of balancing ends and means in the complex world of intelligence operations.