The U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted emergency use authorization (EUA) to a coronavirus vaccine from New York pharmaceutical giant Pfizer on Friday, kicking off a high-stakes effort to immunize millions of Americans buckling under an historic pandemic.

Despite the involvement of an American corporation—in partnership with German company BioNTech—the U.S. was not the first Western nation to give the vaccine the go-ahead. The United Kingdom began injecting citizens with the same vaccine on Dec. 8, and Canadian regulators cleared the way for its use in that country a day later.

The U.S. authorization for the vaccine to be used on people aged 16 and older came on the same day that President Trump seethed on Twitter at his own regulators, echoing a longstanding gripe that the process was not fast-tracked to potentially boost his failed re-election bid. The Washington Post reported Friday that FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn, who along with his colleagues had ultimately pushed back on attempts to rush vaccine approval, was told by White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows to resign if his agency did not OK the vaccine the same day.

Shortly after the FDA’s announcement late Friday that the vaccine had been approved, Trump released a video message hailing the “medical miracle.”

“We gave these companies a lot of money hoping this would be the outcome, and it was,” he said.

The widely respected vaccine’s arrival in the country with the most COVID-19 cases and deaths by far worldwide amounted to a signal moment in a public health crisis that upended almost every facet of modern life in unprecedented fashion.

“I am happily surprised, and so is everybody else,” Arnold Monto, acting chair of the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee, which endorsed the vaccine in a Thursday hearing, told The Daily Beast after FDA scientists embraced the vaccine two days earlier.

He noted that authorities were at one point discussing the possibility of advancing safe vaccines that were proven to be more than 50 percent effective. “And surprise! It’s more than 90 percent effective,” Monto said.

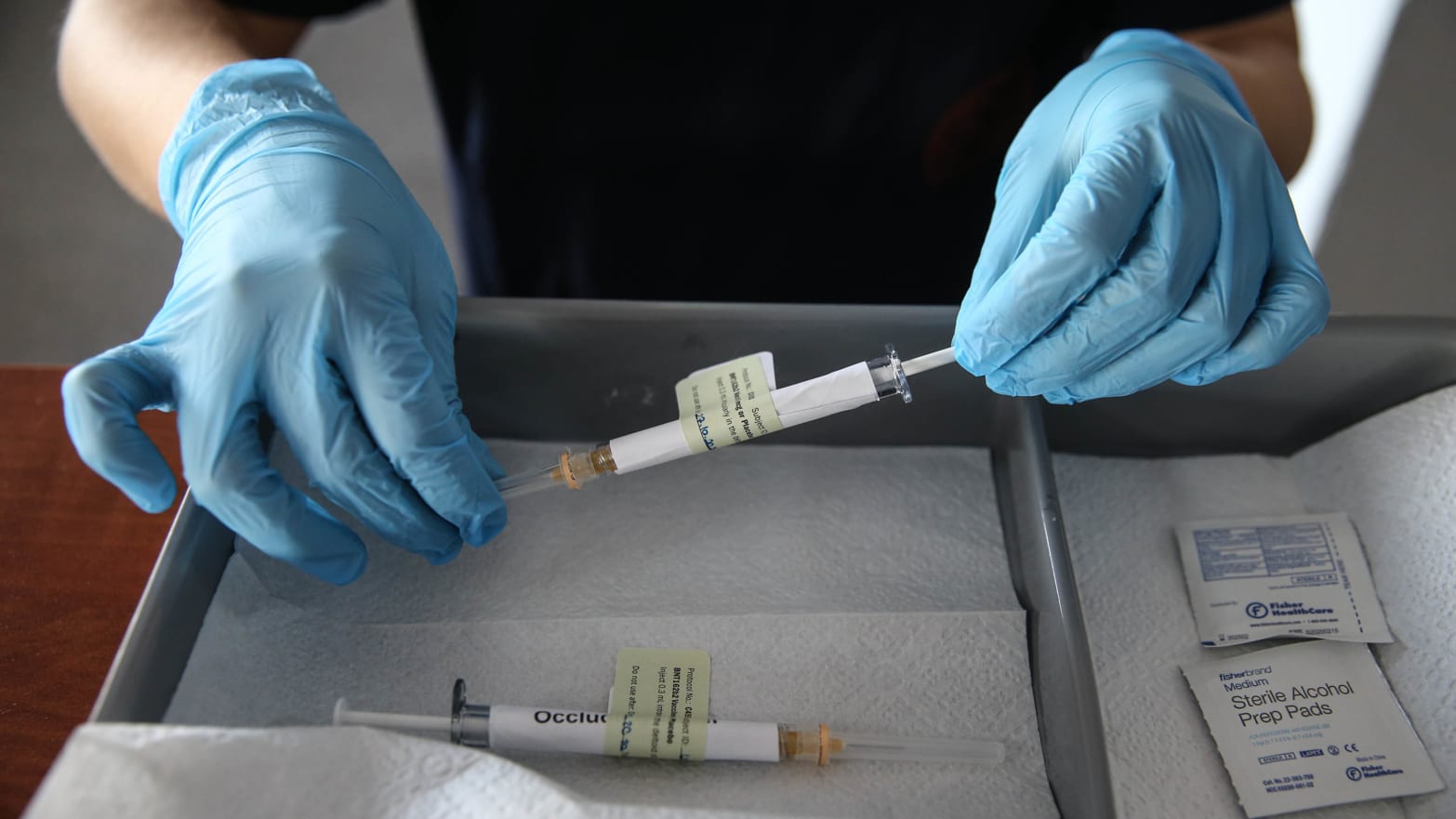

The much-anticipated emergency use authorization, which is not the same thing as full FDA approval, clears the way for the vaccine to be shipped to the hospitals, pharmacies, and clinics that will actually administer doses. The company has projected it could ship some 20 million doses in the United States this year, enough to inoculate 10 million Americans with two doses each.

Pfizer is the first out of the gate in the race to deploy a fully-tested COVID vaccine in the United States, but it’s almost certainly not going to be alone for long. Rival pharma Moderna in Massachusetts has also applied for an EUA for its own vaccine, and could get the green light soon. Both vaccines are based on so-called “messenger-RNA” technology, vaccines that had never previously been rolled out in modern science.

U.K. firm AstraZeneca is in third with a conventional vaccine based on a chimpanzee cold virus. That company’s trials ran into trouble in recent weeks after an error resulted in some test subjects getting partial doses of the vaccine. The foul-up has compelled the company to re-run part of its trials.

Assuming AstraZeneca can swiftly clean up its data, Americans could have access to three different vaccines by spring, at which point the vaccination campaign would gain momentum.

“I would not expect normal in the spring,” Dmitry Korkin, a bioinformatics researcher at the Worcester Polytechnic Institute in Massachusetts, told The Daily Beast. “Possibly in the summer.”

Pfizer’s vaccine and its brand-new MRNA technology breaks down at temperatures warmer than about -100 degrees Fahrenheit. To protect doses during shipping, Pfizer packs the boxes with dry ice. The facilities administering the doses must either transfer them to a special freezer for cold storage, or use them quickly straight out of the box.

Pfizer, Moderna, and AstraZeneca’s vaccines all require two doses. In Pfizer’s case, the shots should occur roughly three weeks apart. Pfizer’s large-scale phase 3 trials indicated the vaccine was nearly 95-percent effective and safe. Side effects were limited to headaches, soreness, and mild fevers.

There’s a catch. “The only thing we do not know for sure right now is how long the vaccine protection lasts,” Lola Eniola-Adefeso, a University of Michigan bio-engineer, told The Daily Beast. Immunity might fade, or the coronavirus might evolve in order to dodge vaccine-induced protections.

Each vaccine might be better suited for particular communities. The Pfizer and Moderna vaccines—with their cold-storage requirement—could be most suitable for bigger and better-resourced hospitals and pharmacy chains.

AstraZeneca’s vaccine doesn’t require the same kind of freezing, potentially making it easier for health-care providers in poor and rural communities to handle. But we don’t know yet how effective it is.

“This is somewhat unusual,” Jennifer Reich, a University of Colorado sociologist who studies immunization, told The Daily Beast. “We have had multiple manufacturers of a single vaccine but not multiple companies with different vaccines that are developed using different technologies.”

Among other things, matching vaccines to communities could help health officials squeeze the most possible benefit from limited supply.

President-elect Joe Biden has pledged to oversee distribution of 100 million doses within 100 days of his Jan. 20 inauguration. That would be enough to vaccinate 50 million people in addition to those who might get their shots before Biden takes office.

But experts estimate that as much as 70 percent of the country will need to get vaccinated—or else have previously been infected with the coronavirus—in order to cut off the virus’s transmission vectors and effectively end the pandemic.

The feds dropped $2 billion to pay for the first 100 million doses of Pfizer’s vaccine and $1.5 billion for Moderna’s first 100 million doses. The government has also pledged $1.2 billion to help AstraZeneca produce 300 million doses through next year. But Pfizer has already had to revise down its more ambitious production targets over supply-chain issues, and the Trump administration reportedly passed on an opportunity to lock in another 100 million doses of the Pfizer vaccine before its trials were completed.

The pressure is on Pfizer to produce and ship as many doses as possible as fast as possible. To boost output and minimize errors as it manufactures potentially billions of doses, the company has upgraded its factories, including a 1,300-acre facility in Kalamazoo, Michigan.

Manufacturing will take time. Pfizer has said it expected to produce some 50 million doses for distribution globally by the end of this year. Moderna also hopes to make 20 million doses of its own mRNA vaccine for U.S. customers alone before 2021.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which crafts vaccination strategy, is advising state authorities to save the initial batches of any vaccine for essential workers and vulnerable groups, including frontline health workers and residents of nursing homes.

Still, it could be April before most Americans can even begin getting vaccinated, Dr. Anthony Fauci, the longtime director of the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, has warned.

There’s one potential shortcut, and it’s a sort of Trumpian one: Tens of millions of Americans who have recovered from COVID probably have enduring natural immunity and could afford to wait to get their shots. But it’s unclear how the government would identify those people and persuade them to move to the proverbial back of the line.

That’s not the only messaging challenge. Health officials must also combat deepening skepticism toward vaccines—skepticism that was exacerbated by the Trump administration’s ultimately unsuccessful campaign to artificially accelerate the vaccine-development process. That skepticism could get still worse in the wake of the apparent last-minute, post-election-loss pressure campaign on the president’s own FDA boss.

Many skeptics are anti-vaxxers who distrust all vaccines, despite reams of evidence that they work and are safe. But some people in communities of color mistrust the authorities who oversee vaccinations—and for good reason. Between 1932 and 1972, the U.S. government tested syphilis treatments on hundreds of Black men in Alabama without informing them of the tests’ true purpose or possible side effects.

Still, experts were hopeful about a widespread embrace of relief from such historic horror.

“My sense is that communities of color may respond favorably to calls to get vaccinated,” James Doucet-Battle, a sociologist and interim director of the Science and Justice Research Center at the University of California-Santa Cruz, told The Daily Beast. “Comprising a large proportion of frontline and essential workers, many in these communities will most likely obtain vaccinations early on.”

“The unprecedented phenomenon of COVID-19 might make it premature to predict a negative response based on past interactions with the medical system,” he added.

Now that Pfizer has the go-ahead to ship its vaccine, there’s no time to waste.

The messaging should include that important caveat: Vaccine-induced immunity could prove fragile—or the coronavirus pathogen might evolve like the flu virus does. And if that’s the case, we might need to do this all over again in 2022 and every year thereafter.

In other words, Pfizer’s vaccine factories might stay busy for years to come.

—with reporting by Olivia Messer