With Democrats furious over Donald Trump, and many Republicans furious over the treatment of Justice Brett Kavanaugh, the 2018 elections are likely to see the highest turnout of midterm voters in recent history.

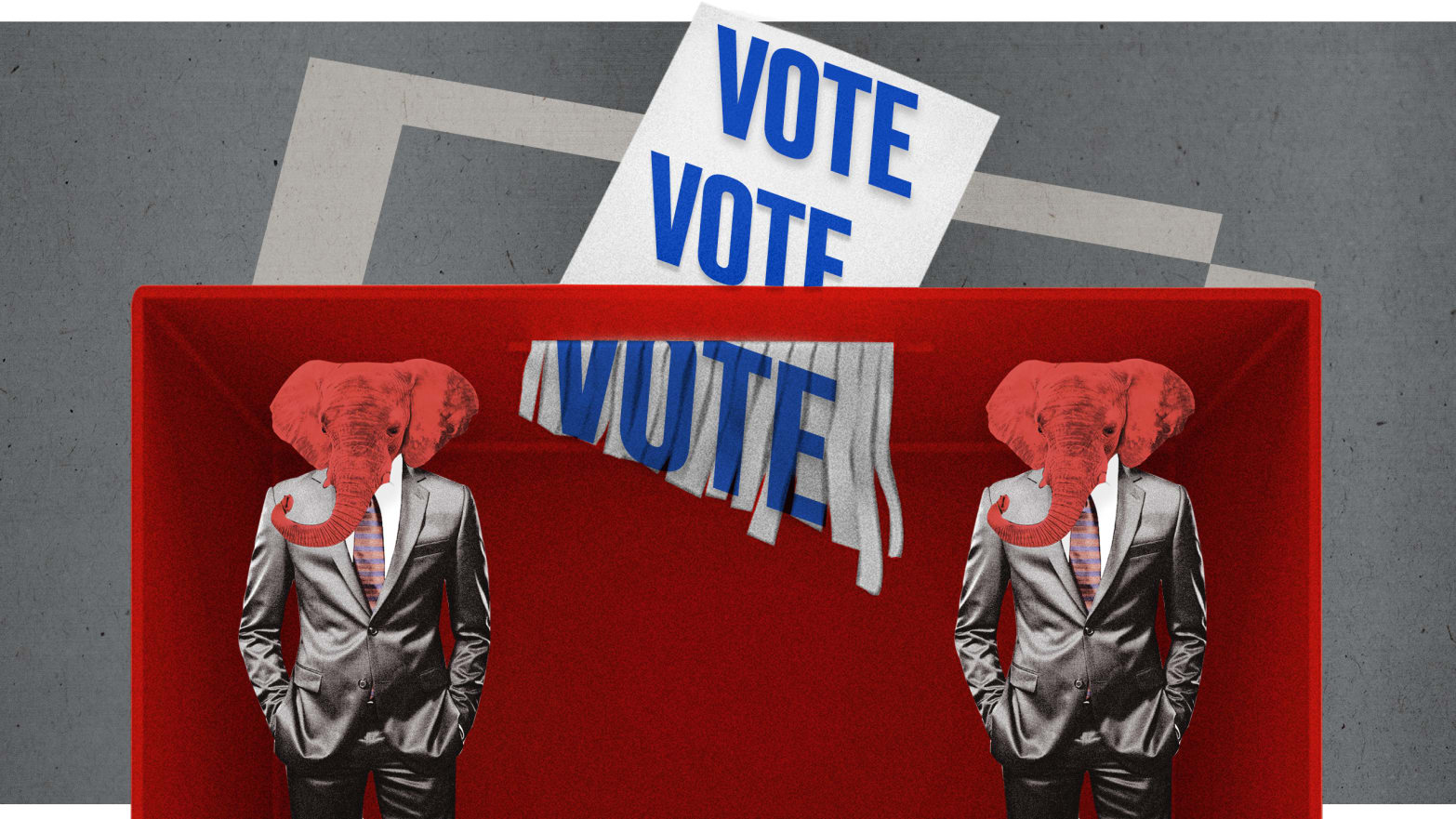

But those voters will be confronted by a byzantine array of voter restrictions, voter-suppression efforts, and voter discrimination standing in their way. A review by The Daily Beast found at least five voter-suppression practices in active use today. All are led by Republicans, all have disproportionate effects on non-white populations, and all are rationalized by bogus claims of voter fraud. They include:

- Closing polling places in communities of color

- Purging eligible voters from the rolls without their knowledge

- Barring felons from voting

- Voter ID laws

- Eliminating early voting

Each one of these alone is troubling. In the aggregate, though, they paint an unmistakable picture of Republican efforts to hold on to power in an increasingly non-white nation by making it harder for non-white people to vote.

The simplest way to stop people from voting is to make it harder for them to vote, and the easiest way to do that is to close polling places. And since 2013, more than 1,000 polling places have been closed in nine Republican-dominated states alone.

2013 was pivotal for two reasons. First, it came after President Obama’s re-election, which shocked many Republicans and which depended—like Trump’s victory four years later—on new blocs of voters turning out in record numbers. According to Carol Anderson, author of One Person, No Vote: The Impact of Voter Suppression in America, the Obama coalition brought in 15 million new voters, mostly young people and people of color. 2012 was when the demographic writing was on the wall.

Second, 2013 is when the Supreme Court decided Shelby County v. Holder, which eviscerated the Voting Rights Act and made it much easier for states and municipalities to enact discriminatory measures. Prior to Shelby County, states with a history of racial discrimination had to secure advance clearance from the federal government before changing voting processes. But Shelby County did away with those requirements, opening the floodgates to voter suppression. In the case of polling places specifically, pre-Shelby County, states had to notify voters if their polling places had changed, but that requirement was removed in 2013.

Since then, a study by the Leadership Conference Education Fund found that 868 polling places had been closed in Alabama, Arizona, Louisiana, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Texas. A second study found 214 polling places (8 percent of the state’s total) have been closed since 2012 in Georgia, where Secretary of State Brian Kemp is now the Republican candidate for governor. He’s running in a dead heat with longtime voting rights activist, Democratic state representative Stacey Abrams.)

While there are legitimate budgetary reasons to close polling places, where they are closed tells a different story. In one Georgia county, local election officials announced plans to close seven of nine polling places in an overwhelmingly black area, plans that were stopped after a statewide protest arose. But according to a Pew Institute investigation, “10 counties with large black populations in Georgia closed polling spots after a white elections consultant recommended they do so to save money.”

As a result of Kemp’s closures, 53 of Georgia’s 159 counties have fewer precincts today than they did in 2012. Of those 53 counties, 39 have poverty rates that are higher than the state average, and 30 have black populations of more than 25 percent. In other words, three-quarters of the counties affected are disproportionately non-white.

John Powers, an attorney with the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution: “There’s no doubt that there is a pattern statewide. Many of the counties in which consolidations are being considered have substantial numbers of minority voters. These precinct consolidations have a disparate impact on Georgia’s most vulnerable citizens.”

In sum, the 2018 report of the nonpartisan U.S. Commission on Civil Rights—a massive, 400-page tome based on voluminous statistical data—concluded that in states like Georgia “cuts to polling places resulted in decreased minority-voter access and influence.”

A second common voter-suppression technique is the purge of the voting rolls based on thinner and thinner pretexts. Voter rolls are supposed to be maintained to ensure accuracy, but lately the criteria for being purged, and the difficulty of getting un-purged, have amplified considerably. And as the Commission on Civil Rights report concluded, “voter roll purges often disproportionately affect African-American or Latino-American voters.”

Once again, Georgia and Brian Kemp provide a chilling example. This week, the Associated Press revealed that Kemp has implemented an “exact match” policy that disqualifies voters if their names do not precisely match records held by the Georgia Department of Driver Services or the Social Security Administration. Typos, missing hyphens, or clerical errors cause voters to be purged unless they can prove the purge was in error.

As of Oct. 9, 53,000 voters are in limbo because of this requirement—and 70 percent of them are African Americans, AP reported. Georgia’s population is 32 percent African American.

Moreover, journalist Greg Palast laboriously combed through the list of purged voters and found thousands of names that were erroneously purged, such as people who had moved, or even switched apartments in the same building. Yet unless these voters actively take the step of contacting the state of Georgia, they may not be allowed to vote on Nov. 6.

There’s no doubt as to why Kemp is doing this. In a closed-door session of Republican politicians last July, Kemp said, “The Democrats are working hard. There have been these stories about them, you know, registering all these minority voters that are out there and others that are sitting on the sidelines. If they can do that, they can win these elections in November.”

Kemp cited the risk of voter fraud, but his own office’s investigation in 2014 found only a few dozen potentially fraudulent voter applications among tens of thousands that were investigated. While voter fraud is fake, voter suppression is very real.

With Georgia’s population of 10.4 million and an estimated 50 percent voting rate, those 53,000 purged votes represent a full percentage point of voters, enough to swing this close an election.

A second key instance of voter purge is Ohio, where a Supreme Court decision in June allowed a controversial voter-purge policy: If you fail to vote for two elections, you’re sent a notice; and if you don’t answer the notice, you’re purged from the rolls.

Once again, to get a sense of what that means, check the numbers. In 2016, 2.2 million Ohioans didn’t vote. In 2014, 4.6 million didn’t. If you assume that the 2016 non-voters probably sat out 2014 as well, that means 2.2 million people have now been sent a single mailed notice that they had to send back to get put back on the rolls in time for the 2018 election.

We don’t know how many sent back that notice. We do know that Trump won Ohio in 2016 by 446,821 votes, just one-fifth of those who could be purged. And, once again, the Ohio process disproportionately affects those at or near the poverty line, who may not understand the legalistic notice, or may not receive it because they moved, or may be suspicious of sending any such form back to the government.

One of the most impactful suppression tactics is a legacy of Jim Crow: barring felons from voting, even after their sentences are complete, as happens in Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia—all former Confederate states. As a result, in those states, more than 7 percent of the total voting-age population is disenfranchised because of criminal convictions. (The other states in the South allow felons to vote after completing their sentences, in addition to any probation or parole.)

Today, 6.1 million Americans are denied the right to vote because of current or past felony sentences.

There is ample historical evidence that this policy was racist from the start. In 1896, the Mississippi Supreme Court ruled that the limitations on voting were intended “to obstruct the exercise of suffrage by the negro race.” And yet, it remains legal.

As a result, according to a 2016 study by the Sentencing Project, in four states more than one in five black Americans is disenfranchised—Florida (21 percent), Kentucky (26 percent), Tennessee (21 percent), and Virginia (22 percent)—due to policies of mass incarceration, crime rates in communities struggling under economic and racial oppression, inequality of opportunity. No wonder it’s called the “New Jim Crow.”

Florida is now the test case for felon voting. In Florida, felons can only get their voting rights back if they personally petition the state. After his predecessors of both parties expedited the process of restoring voting rights, Republican Gov. Rick Scott (now running for U.S. Senate) implemented an arbitrary, mandatory five-year waiting period for those who have completed felony sentences to be able to vote again. This arbitrary rule was upheld in court last April.

Consider the numbers once again. As a result of the law and Scott’s extension of it, 1.5 million Florida voters are barred from the polls. Florida’s population is 21 million; its turnout rate in non-presidential elections is around 50 percent. And since the current polls in the Florida gubernatorial election have Democrat Andrew Gillum leading Republican Ron DeSantis by 3 percentage points, that means the margin between them is approximately 300,000 votes.

In other words, the number of disenfranchised voters is five times the current margin in the race.

Moreover, Florida’s policy hits black Americans twice as hard as white folks: In 2016, felon disenfranchisement excluded more than 10 percent of the voting-age population overall, but more than 20 percent of black Americans.

This fall, Florida has a constitutional amendment on the books that would do away with the petition process, and automatically restore voting rights once felons have completed their sentences. A recent poll indicates that 71 percent of Florida voters support the measure.

That is good news for democracy. Granted, to many people, barring felons from voting makes some degree of sense. But why? If you think about it, committing a crime doesn’t mean you’re no longer a citizen—you still have to pay taxes, for example. And crimes ought to be punished by the sentences imposed by juries and judges, not disenfranchisement rules put into place by racist state legislatures in the 19th-century post-Confederacy. It’s not by coincidence that felon voting bans hit minority communities more. It’s by design.

For many people, carrying photo identification is no big deal. I show my ID all the time: to get into the office, to board a plane, to get into a bar.

But that is just not true for everyone. In fact, 3 million Americans lack photo IDs, and because the most common photo ID is a driver’s license, the people least likely to have them are less affluent people in urban areas—disproportionately people of color. That’s why, for the last 40 years, polling places have matched signatures rather than photographs, enabling people to vote without an ID. But following President Obama’s two victories in 2008 and 2012, that began to change. Fifteen states enacted voter-ID laws, again with the false claim that voter fraud was a runaway problem.

In 2016, such laws were struck down by courts in Texas, North Carolina, and Wisconsin. But many other laws persist. And, the Commission on Civil Rights report found, “strict voter-ID laws typically produce the greatest burden for African-American and Latino-American communities” and “correlate with an increased turnout gap between white and minority citizens.”

This week, the Supreme Court allowed North Dakota’s onerous voter-ID law to remain on the books and enforced for the 2018 election cycle. That law requires specific forms of ID and proof of residence, both of which many Native Americans lack. In particular, many Native Americans do not have traditional residential street addresses, meaning they simply cannot comply with the new law.)

The requirements were put into place by Republicans after Democratic Sen. Heidi Heitkamp’s razor-thin victory in 2012, together with a host of other rule changes that make it harder for Native Americans—who make up about 5 percent of the state—to vote. This year, Heitkamp is facing a tough re-election race against a Republican challenger.

America is one of the few democracies where Election Day takes place on a workday, which makes it very hard for parents who have to juggle work and childcare to vote. That, in itself, is a kind of voter suppression.

To compensate, most states have implemented early voting, opening the polls days before Election Day to enable people to vote. After 2008 and 2012, that trend was reversed. In North Carolina, for example, the Republican-controlled legislature and Republican governor eliminated early voting days in 2013, even though in 2012, 900,000 voters cast their ballots during the early-voting window.

Why? Take a look at the numbers. In 2012, 48 percent of North Carolina’s early voters were registered Democrats and 32 percent were registered Republicans; that means that 140,000 more early-voters were Democrats. In 2012, Mitt Romney won the state by 92,004 votes; in 2016, Donald Trump won by just 173,315 votes.

In other words, had early voting not been eliminated, Trump’s victory margin would’ve been just one-fifth of what it was. It would practically have been a tie—and that’s not counting North Carolina’s other voter-suppression efforts.

Another example is Florida, where Gov. Scott rolled back early voting at university campuses, where voters tend to be younger and more liberal. This policy was halted in July by a federal judge, who noted that 830,000 students were enrolled at state colleges and universities. Even so, three Florida universities announced they still would not enable early voting at their campus polling places.

Now, these five voter-suppression policies don’t even include some of the most insidious disenfranchisement practices happening today: extreme gerrymanders that benefit one party over another, or redistricting efforts that “crack” minority communities into multiple districts or “pack” them all into one, diluting their power. These practices, both of which have recently been allowed to proceed by the conservative-led Supreme Court, arguably weaken the power of minority voters more than voter-suppression campaigns do.

But voter suppression is unique in that it directly blocks voters from voting. It is a direct affront to their citizenship. And it is all based on a lie: that voter fraud is a crisis.

In fact, there simply is no voter-fraud crisis. An exhaustive study by a Loyola law professor found that between 2000 and 2014, there were all of 31 reported instances of in-person voter impersonation. Out of more than a billion votes cast. In other words, the odds are 1 in 32 million that a vote is fraudulent—certainly not enough to swing any election. And by way of comparison, you are 237 times more likely to be struck by lightning.

In the fact-free universe of Fox News, Sinclair, Breitbart, the Murdoch-owned Wall Street Journal, and the rest, it doesn’t matter that there is no voter-fraud crisis. They’ll just make one up. Remember, the president of the United States has alleged, without a scintilla of evidence, that between 3 and 5 million people voted illegally, a claim that every expert in the field has said is implausible to the point of absurdity.

As a result, three-quarters of Republicans said that voter fraud happens “somewhat” or “very often,” including 68 percent of Republicans said that millions of illegal immigrants had voted in 2016. Both completely, unequivocally false.

Likewise, one would think that the career of Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach, a Republican, would be harmed by his humiliating, devastating losses on the “voter fraud” issue. First, Kobach lost in federal court, when it was found that his anti-fraud crusades, which suspended 36,000 Kansas voters (once again, disproportionately people of color), was totally unjustified. (It found exactly three cases of possible fraud, all of which were mistakes, in which senior citizens voted in two states by accident.) And if that weren’t enough, Kobach was humiliated again on the national stage, when the voter-fraud commission he chaired folded without finding a single case of fraud.

And yet, Kobach is now running for governor of Kansas, and might just win.

If there is a silver lining, it’s that this year there are efforts to turn back the tide. Dale Ho, director of the ACLU Voting Rights Project, told The Daily Beast that “there are more pro-voter ballot initiatives this year than perhaps any election in recent history. These include the restoration of voting rights to people who have served their time in Florida, wholesale modernization of the elections system in Michigan, automatic registration in Nevada, Election Day registration in Maryland, and nonpartisan redistricting in Utah. Voters have a chance to take matters into their own hands.”

Ultimately, the Republican voter-suppression scam is just about math. There are too many black and brown people in the country for the Republican Party to retain power with a narrow base of white support. If there weren’t systemic voter suppression, the states of Texas, Ohio, Florida, North Carolina, and Georgia would likely be Democrat-led today or in the very near future. So what choice to Republicans have but to forestall the inevitable and prevent people of color from voting for as long as they can?

As Ho put it, “the techniques of voter suppression change, but the constant is a continuing push by elected officials whose power is threatened by demographic shifts in the voting populace to try to curate the electorate and boost their chances of retaining power.”

Republican strategist Paul Weyrich said it best in 1980, when he stood beside Ronald Reagan at an evangelical gathering. “I don’t want everyone to vote,” he said then. “Elections are not won by a majority of the people… As a matter of fact, our leverage in the election quite candidly goes up as the voting population goes down. We have no responsibility, moral or otherwise, to turn out our opposition. It’s important to turn out those who are with us.”