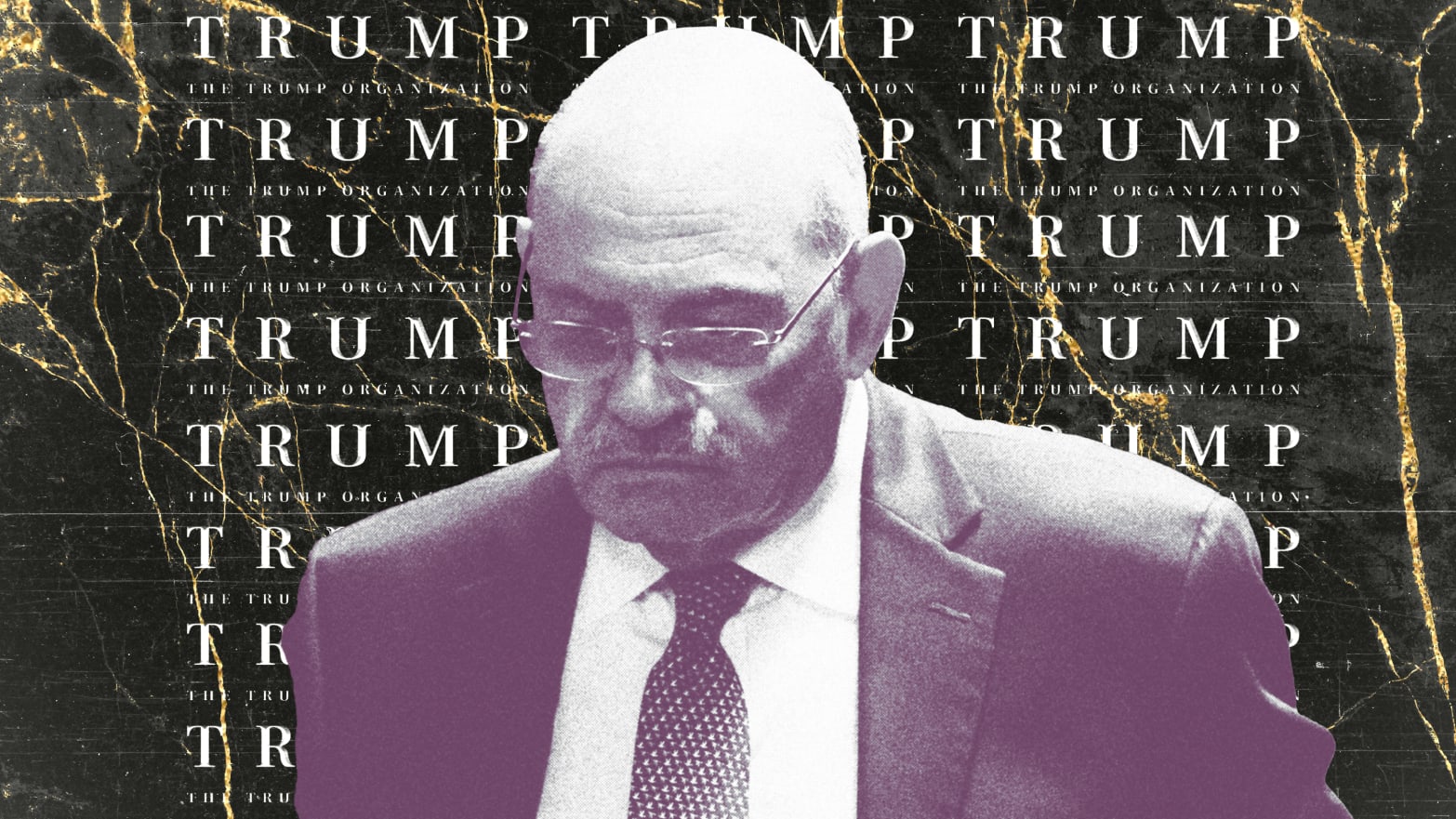

Disgraced Trump Organization executive Allen Weisselberg was nearly brought to tears on Thursday during his testimony at the company’s criminal trial, where he admitted to betraying the former president’s family and putting them at legal risk by dodging taxes and fudging the books.

And yet, he remains loyal.

Despite his plea deal with prosecutors to become their star witness, Weisselberg has made himself a fall guy. The Manhattan District Attorney’s Office, which has been frustratedly building a case against former President Donald Trump by trying to flip his lieutenants, has hit a wall.

Weisselberg spent his second day on the witness stand absorbing all the blame, saying he alone rearranged his pay and benefits to avoid taxes, blowing holes in the DA’s theory that the company as a whole engaged in tax fraud.

“It was my own personal greed that led to this,” he said in his gravelly voice.

Weisselberg is giving both sides what they want, agreeing to every question asked of him by prosecutors and company defense lawyers. As a result, jurors are seeing what appears to be a remorseful executive who committed crimes—all on his own.

In the morning, Weisselberg acknowledged how he avoided paying some of his taxes by diverting it into untaxed luxury apartment rent, utilities, and a parking garage worth more than $100,000 a year.

“I was guilty of those crimes,” he said.

Then in the afternoon, Weisselberg clarified that he did all of that on his own—and if anyone knew about what was going on, it was only his underling, company controller Jeffrey S. McConney, who conveniently has already struck an immunity deal with the DA’s office. Weisselberg insisted that the scheme operated criminally without the knowledge of Donald Trump or the offspring he appointed as executives there: Don Jr., Ivanka, and Eric Trump.

Alan Futerfas, the company’s defense lawyer, scolded Weisselberg.

"The individuals who own this company relied on you… to do the right thing… you had a history going back almost 50 years,” he said, pointing out that Weisselberg joined the Trump Organization when Trump’s oldest child, Don Jr., was just 5 years old. The patriarch’s right hand moneyman witnessed Trump’s children grow up and was there to guide them when they returned after college to work at the family firm.

“You were among the most trusted people they knew?” Futerfas jabbed.

“Correct,” says Weisselberg, his voice now shaky, eyes turning red.

“Did you honor the trust that was placed in you?”

“No.”

“Did you betray the trust that was placed in you?”

“Yes,” he said, on the verge of tears.

“And you did it for your own personal gain, correct?”

“Correct.”

“Are you embarrassed because of what you did?"

“More than you can imagine.”

Weisselberg was hunched over now, his voice cracking.

“Are you ashamed?” Futerfas asked.

“Very much so,” Weisselberg said.

Despite his reluctance to implicate the Trumps, Weisselberg did, however, show the jury what a rats' nest of criminality the Trump Organization has been over the decades. The financial executive admitted that a huge proportion of his salary was paid as if he were an “independent contractor,” never mind the fact that he was working at the Trump Organization as a salaried employee. Companies don’t withhold taxes from income or submit payroll tax to the government for independent contractors, so this fix allowed both Weisselberg and the Trump Organization to dodge taxes.

Weisselberg revealed that a bunch of “senior executives got paid this way.”

“It started back in the ’80s, before I even began to work in New York,” he said, without naming anyone who may have been responsible for the arrangement at the time.

Weisselberg also laid out how he and other executives extended this charade into their future retirement. Although the company already offered a 401k, they nevertheless spun up tax-deferred “Keogh” plans, which are meant for the self-employed—allowing them to retire from independent contractor jobs they never had.

Weisselberg revealed that Donald Bender, the outside accountant at MazarsUSA who had prepared the company’s taxes for decades, was fully aware that executives were splitting their pay between legitimate W2 forms meant for salaries and 1099 forms meant for independent contractors.

“He didn’t love the idea,” Weisselberg said.

Meanwhile, the Trump Organization kept this up even as Trump declared his first presidential run and eventual success. Weisselberg said the cleanup only started in 2017, “when Mr. Trump became president... to make sure that we correct everything.”

The public finally got to hear for the first time how exactly it came to be that Trump ended up paying for his CFO’s grandchildren’s tuition at the exclusive Manhattan academy known as the Columbia Grammar & Preparatory School—in a way that was also not taxed. Weisselberg recalled how a decade ago, he and the boss were discussing business in the future president’s office on the 26th floor when suddenly Don Jr. walked in with paper copies of his children’s private school tuition bills.

"I might as well pay for your grandkids too," the now-former president joked. Weisselberg chuckled and left.

Days later, Weisselberg showed up at Trump’s office holding the bill for his grandkids’ private school. After all, they weren’t too removed from the company. Their father—Weisselberg’s son—is Barry Weisselberg, who was running the company’s operations of the Central Park ice rink.

“Here I am. Here’s the bill,” Weisselberg told him. Trump drew his initials on the form.

“Don't forget, I’m going to pay you back for this,” Weisselberg said on his way out.

But the payback came in the form of diverted income. Weisselberg reduced his yearly income by tens of thousands of dollars to cover the cost of the private school, saving the company and himself from paying taxes. Does that implicate Trump? Weisselberg wouldn’t have you think so.

Futerfas grilled him on what he called a “totally spontaneous gesture.”

“You’re the one who decided how you’re going to pay it back, right?” the lawyer asked.

“Correct,” Weisselberg said.

“You never told Trump you’re deducting it from your compensation, did you?”

“No,” he said.

But it’s not like Weisselberg is testifying about this under duress. Earlier this week, he revealed that while he’s no longer CFO, he still does much of the same work he did before. He even earns the same pay. And he’s still expecting a handsome $500,000 yearly bonus as usual on Jan. 2, 2023, he said in court.

“Hopefully,” he answered Tuesday when asked if he still planned to get his bonus.