Well, it would be a bit awkward if the New York City Center Encores! production of Stephen Sondheim’s Into the Woods, opening on Broadway tonight (St. James Theatre, to Aug. 21), was not as wonderful as the original production of only two months ago. Fortunately, with a few cast changes, this remains a shimmeringly gorgeous production, directed with such care and flair by Lear deBessonet—and the best tribute imaginable to the master himself, who died at age 91 last November.

The Encores! production commanded lines around the block for its May engagement, and the audience for its Broadway production is buzzing as it takes it seats, rapturously applauding throughout, and thunderously ecstatic, standing as one whooping and clapping, at the end. Do all you can to book a ticket. This is a theatrical event to see and to savor.

The show, packed with stars clearly having the times of their lives, is both extremely funny and profoundly moving, switching between both registers in a blink at certain moments, while in the second act letting its emotional power grow and coalesce until you should, if you have a functioning heart, be in snuffling streams of tears.

It is beautifully sung, witty, the orchestrations (by Jonathan Tunick; music director Rob Berman) are lush and precise. This critic’s only cavil is that it was wonderful to see the production on Encores’ bigger stage in May; it does not feel squashed at the St. James (the simplicity of David Rockwell’s design remains, distinctive for its descending tubular trees), but that larger stage helped open the text so expansively. It feels more polished now inevitably; that is to be expected.

This Into the Woods crystallizes the show’s larger political messages. It is absolutely impossible not to listen to Sondheim’s lyrics and watch these characters confronting a merciless giant and not feel the political desperation of this moment, around our degrading democracy and its wannabe despots, opportunists, and activist judges seeking to restrict the freedoms of others—whether it be attacking a woman’s right to control her own reproductive destiny, LGBTQ equality and trans youth, or the right itself to vote—or, well take your pick, they will all buzz around your mind as you sit, entranced by this magnificent show.

Sondheim doesn’t bang an obvious metaphorical drum; our minds do the mapping in the amazing spatial arena he creates for us in lyrics and book (by James Lapine). We really see why going “into the woods” is both terrifying and liberating to this gallery of familiar fairytale characters; why true bravery can be experienced in the strangest ways; what love means; what justice can look like; how community should behave; what grief is; and what “family” means. All of this is somehow lightly and deeply scored into text and lyrics, straight into our ears, hearts, and minds. And so comes all the laughter, and all the tears.

Aymee Garcia, Cole Thompson, with Kennedy Kanagawa operating Milky White.

Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman for MurphyMade

The repeated incantation “Children will listen” sounds like a lullaby and also—for this critic, considering the onslaught of anti-LGBTQ and other bigotries in this moment—also a furious caution to those stoking the fires of prejudice and social and cultural restriction. The other repeated incantation, “No one is alone,” is just as powerfully rendered. (Not that they would ever listen, but still—make Into the Woods compulsory viewing for the likes of Republican governors like Ron DeSantis and Greg Abbott, and, across the pond, every Tory candidate canvassing to succeed Boris Johnson, proudly and pathetically flying their anti-trans colors for votes.)

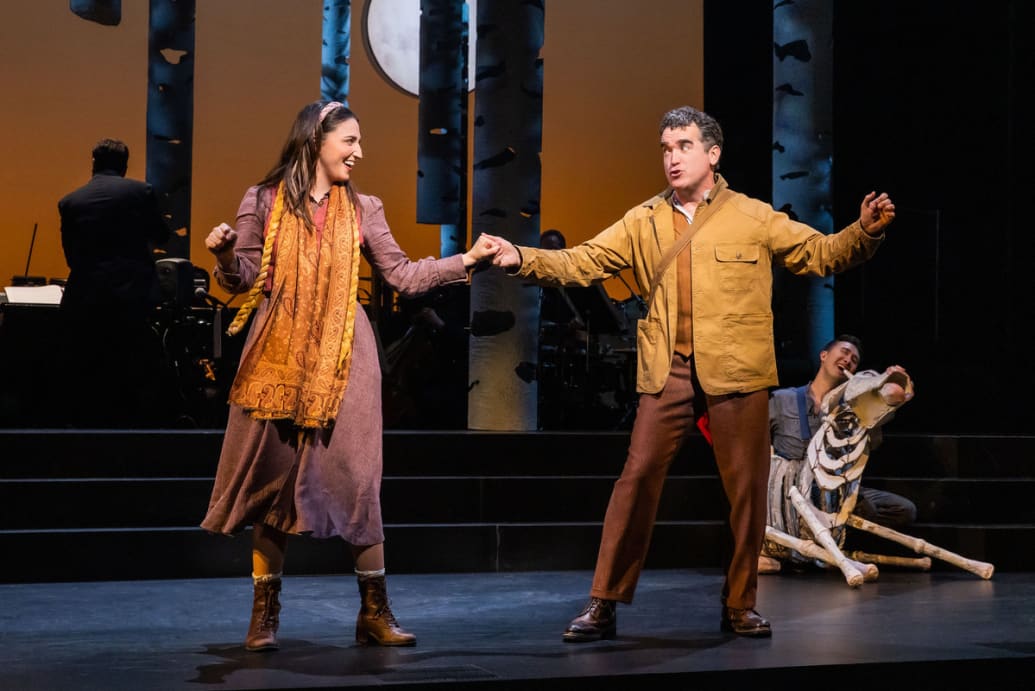

Brian d’Arcy James replaces Neil Patrick Harris as the Baker and Sara Bareilles his wife, desperate to have a baby and set an impossible set of tasks by the Witch (Patina Miller replacing Heather Headley) in order to have their wish granted. Miller begins the show hunched and threatening, stabbing her stick toward d’Arcy James’ groin and Bareilles’ womb, a cloud of gray curls obscuring her face, and then, ta-da, just wait for her glamorous transformation and her powerhouse renditions of “Stay With Me,” “Witch’s Lament,” and finally “Last Midnight,” when Tyler Micoleau’s lighting—a beautiful palette throughout—becomes its own stunning rainbow-hued micro-performance.

Against her, or indeed anyone, d’Arcy James is a furrow-browed squirrel in headlights, and then a hero despite himself. He has a lovely comic and moving chemistry with Bareilles, who refuses to stay home and wait for him to collect all of the Witch’s demands from the woods. Bareilles’ command of this role was evident in May, and now has an even smoother and winning authority with it.

Sara Bareilles as the Baker's Wife and Brian d'Arcy James as the Baker.

Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman for MurphyMade

Her final song, after an unexpected, passionate wooing, “Moments in the Woods,” is a meditation on what her life is, what possibilities there could be, and the power of “and” rather than “or”—an argument for the expansion of possibility in life to always bear in mind even when life restricts us. The song makes you appreciate the genius of Sondheim’s lyrics, so open to the strangeness of human hearts and motivations. The roof-raising round of applause that follows is down to Bareilles’ formidable interpretive skills, making sense of them.

The production laughs at itself and its absurdities when it needs to, and also takes itself absolutely seriously. Phillipa Soo replaces Denée Benton as a canny Cinderella, faced with a prince-related decision to make. One has to feel for Cinderella; she has the least amount of fun on stage, and must play the straightest—and all credit to Soo making as much of tumbling over and talking birds to make us laugh.

The entire stage-stealing Julia Lester, who made a winning New York theater debut as Little Red Ridinghood at Encores!, returns to the role on Broadway, rolling her eyes and not buying anything anyone is saying, and taking the air and mystery out of anything crazy happening around her. Cole Thompson is a sweetly off-kilter Jack, frustrated at having to face the giant, when really he just wants to be reunited with Milky White, his cow, designed by James Ortiz and operated as a puppet by Cameron Johnson—for this performance, covering for Kennedy Kanagawa—with such impressive dexterity that we follow his every movement and expression. The audience adores Milky White, even the physical comedy involved when he “dies.”

Gavin Creel plays both the wolf foolish enough to torment Little Red Ridinghood, and then Cinderella’s vain and extremely hot prince, who is a catch and isn’t a catch, and despite the leaping flourish he appears with—just like Rapunzel’s prince (Joshua Henry)—is shown as sadly lacking. (And he knows it, as Creel wittily shows.) The price of admission is worth seeing Creel and the equally excellent Henry sing “Agony” as a dueling, overblown diva duet flinging shoulders and pouts at each other. There’s a welcome reprise of their over-expressive feast in Act Two.

Gavin Creel as the Wolf and Julia Lester as Little Red Ridinghood.

Matthew Murphy and Evan Zimmerman for MurphyMade

Aymee Garcia plays Jack’s long-suffering mother, despairing of his innocence and then just movingly despairing. David Patrick Kelly is our narrator and a mysterious man, eventually drawn against his will from his safe perch of apparent omniscience; and David Turner is a stone-faced steward who stands for all those who myopically dispense and abuse the power they are given.

After the various fairytales are resolved at the end of Act One, Sondheim takes the audience beyond the traditional happy-ending fruition of the stories in Act Two, with more laughter and even more tears as everyone heads back into the woods, to face a none-too-happy giant. Here, all the show’s larger messages around revenge, justice, and love come into sharper focus. Some things seem untenable, others impossible to come back from. Again, Sondheim and this company don’t wrench things into a happy ending, but it is an ending that points to futures being shaped from tragedy by determination, wit, circumstance, a belief in mutual care and responsibility, and sheer force of will.

The final three songs of the show, “No More,” “No One Is Alone,” and “Children Will Listen,” take you through a landscape of emotions—and the entire philosophical terrain of the show. How do we confront grief and hopelessness? How can we stand up against utter tyranny and malevolence? How can we keep doing it? And when nothing is left, what can and what should we build for ourselves? How large and embracing can a new notion of “family” be?

Sondheim does not offer clear answers, but instead guides his characters and us through mazes of lyrical possibility toward a clearing of somewhere refreshingly simple and stark. Life will be messy and painful, but it can and must continue, and here we are. There is, of course, an element of catharsis to it all; but there is also something more urgent—a call to action, a call to standing up against tyrants and those who seek to destroy and dominate—and from that, if one is still alive, gaining not just a sense of comfort but also of vital and sustaining community, and fighting proudly for that.