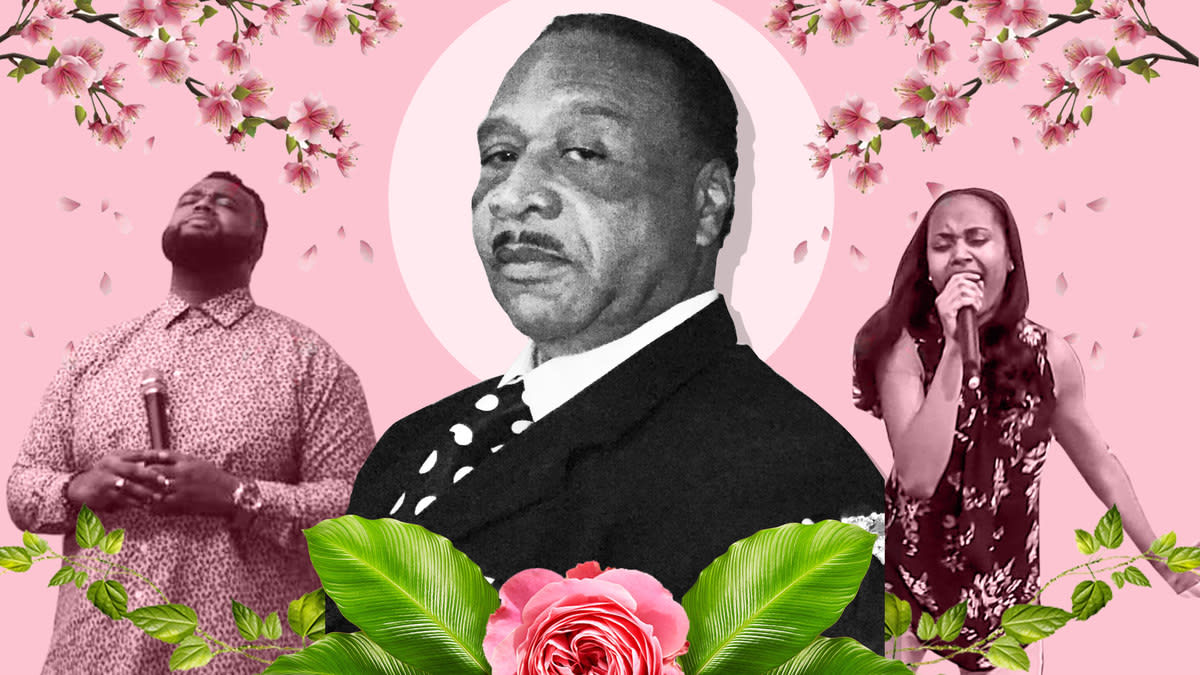

John Richardson Jr. was a storyteller who loved his coffee and his cars.

At 65, he was at the dawn of retirement from an asphalt plant, maintaining his passion to see the country beyond his hometown of Albany, Georgia. When he wasn’t thinking of the next trip, Richardson—who saved meticulously—devoted his time to six grandchildren and caring for a six-car collection that included a two-door Mercedes, an Infiniti and, perhaps his favorite, a 1990 Lexus.

In an interview, his son-in-law, Orson Burton Jr., chuckled as he recalled an animated Richardson describing the car’s bright future just a few weeks ago.

“He has 220,000 miles on it, and he was like, ‘Yeah, I'm 'bout to go change the alternator and I'm gonna run it until it's about 500,000 miles on it,’” Burton told The Daily Beast.

Then, on April 4, Richardson succumbed to the novel coronavirus ravaging America.

“It was unreal.” said Burton, who serves as pastor of Harvest Time Fresh Start, a predominantly black, nondenominational church in Albany. “That's the best way to describe it. Like, we were just in the yard, talking about fixing his Lexus. And three days later, four days later, he made it to the hospital, and we never had an opportunity to see him again.”

Burton has seen the crisis in painfully personal ways—and how it can test institutions at the heart of a community in need.

After all, Richardson’s case reflects the painful reality of Albany, seat of Dougherty County. African-Americans make up 68 percent of the county’s population, but a far greater majority of local deaths from the coronavirus, according to County Commissioner Vince Edwards, who said he knew 16 people himself—all black—who have died in the last three weeks. “The impact is tremendous,” he said, “and feels like it is growing.”

Two weeks ago, blacks comprised 90 percent of COVID-19-related deaths in the county, according to Michael Fowler, Dougherty County Coroner. With a recent surge in white fatalities, that percentage has declined some, to the high 70s, he said Wednesday. Nationally, African-Americans have likewise been hit disproportionately hard by the coronavirus, including in Louisiana, where despite making up about about 32 percent of the population, they accounted for roughly 70 percent of deaths.

On the surface, Albany, a city of 75,000 a few dozen miles from the nearest interstate, might seem like a misfit in news media coverage when listed among other hot spots for the virus like New York, Seattle, New Orleans, and Detroit. However, with 1,310 cases and 83 deaths as of late Wednesday, it has attracted national attention for the volume of suffering, and for two funerals that helped set off a local outbreak in late February and early March.

“We're a Southern community,” Burton told The Daily Beast. “We're big on family, big on church and everybody kind of knows everybody. So, um, people were just paying their respects.”

The pastor has lost his father-in-law, but also seen neighbors and members of his flock continue to be hit hard.

In response, the church has launched a series of street prayers throughout the community with leaders speaking through a bullhorn—walking six feet apart—to demonstrate social distancing.

But the coronavirus has thrown uncertainty into some of the church’s projects at a time of renewed hardship. For example, the church’s research concluded that 70 percent of city residents were renters, and most of them African-American. So the church had launched a project to renovate houses and sell them at affordable prices.

This project is now stalled because Joey Harris Sr. a developer helping direct the effort, died of coronavirus, as did his daughter, Santayana Harris, an active member of the church, according to Burton.

Other members of the congregation have tested positive and recovered.

Charlee James, a member of the church and graduate student studying social work at Albany State, describes herself as a homebody. She did not attend either of the two funerals that gained so much outside attention, nor a local marathon that some in the area suspect contributed to the spread. By the time her symptoms appeared, her classes had moved to Zoom, and church services were remote, she said.

“All I had at first was a slight sore throat,” said James, who works as a counselor at a local juvenile detention center. “I was like, ‘I’ll be fine, I’ll take some time off. I’ll be back to work in a week, but that’s not what happened.”

She spent a week in the hospital, and is now recovering in quarantine.

Unlike James, John Richardson, Jr attended one of the funerals, according to his daughter, Somika Carr. Of his four children, Carr said she was the closest to him and the one he first called in late March, when he became sick with what he thought was just a bad cold.

By that time, the spread of the virus in Albany had made national news. So, to be on the safe side, he went to the hospital and was treated for an upper respiratory infection, Carr recalled. He was tested for COVID-19, and returned home to wait for results.

Five days later, the normally energetic Richardson was tired and had trouble breathing. He returned to the hospital. Several days after that, the results came in: positive.

In his final days, Somika Carr was so close yet felt so far away from her dad. A nurse at Albany’s Phoebe Putney Memorial Hospital—where ICU beds, personal protective equipment (PPE), and other resources have been severely strained due to the outbreak—she suffers from an auto-immune condition. That meant she was assigned to areas of the hospital that were not devoted to coronavirus patients, but also that she was not allowed to visit her father.

There were times she considered breaking the rules and using her badge to enter the unit where her father suffered during the last days of his life, but resisted.

“It’s very difficult because you cannot see your family members and they’re dying alone,” she told The Daily Beast.

During the first two days of his second hospital visit, Richardson was on an oxygen machine and Carr could talk to him by phone, she recalled. It was on that second day that she had her last conversation with him.

“He was just telling me he was tired,” she said. “It was about ten something at night, and he wanted to get him some rest. He said how strong the oxygen was blowing in his nose, and he didn’t like that feeling. And I said, ‘OK, daddy, just get you some rest, We’ll talk tomorrow.’ And tomorrow never got here, because I never spoke to him again.”

The next day, Carr received a call from Linda, her stepmother and Richardson’s wife, who told her he was moved to the critical care unit. The plan was to put him on a ventilator because he was having trouble breathing. But his condition worsened, his blood pressure dropped to dangerously low levels, and his kidneys were failing, she said.

Three days later, he was gone.

“And I just was numb, it was just like I was in a movie. I just didn’t know what to do,” she said. Richardson was buried in a graveside service with 10 people practicing social distancing.

For Reverend Burton, Richardson’s death was so sudden—yet also reflective of the sorrow that has come to define the black experience in Albany.

“I don't know an African-American family who has not been impacted directly, that is in immediate family or in circles of influence,” Burton said. “We have been disproportionately dying here.”