The Bloody and Tragic End of Scientology’s Biggest Pop Star

Photo Illustration by The Daily Beast / Photos Getty

His name was Kuba Ka, and he called himself the “God of Pop”—having allegedly been handpicked by Michael Jackson’s manager as his successor. Then his face began falling off.

On April 22, the day before he died, Jakub Stepniak recorded a phone message for one of his doctors.

He is barely audible in it. He thanks his doctor for calling him and, barely above a whisper, says that he is there with his uncle, and that “the inflammation is so bad.” He then says something about trying to reach another doctor. And he finishes the message with an ominous final utterance: “I don’t know if I’ll survive to the morning.”

The next day, on April 23, Stepniak’s uncle, Danny Maghen, who was staying at his apartment, found Jakub unresponsive. He had died in his sleep.

Five years earlier, Stepniak celebrated his 25th birthday in Santa Barbara, California, with his father Andrzej, a Polish economist, and two of his entertainment handlers, Vikki Lizzi and MJ Lord. The occasion was captured on video, and Andrzej, smiling, holds up a placard that proclaims his son, “Kuba Ka, the God.”

Originally from Poland, Kuba Stepniak (“Kuba” is a common shorthand for “Jakub” in Poland), achieved some local fame as an upstart child who made charity events happen with big international stars around the turn of the century. Then, after some sort of trouble in his home country, he reemerged in Hollywood years later as an “international pop star” by the name of Kuba Ka. He put out a song with Flavor Flav, appeared on the E! network in a short-lived reality series, and unironically began calling himself the “God of Pop.” After a brief flirtation with Scientology in 2017 ended in disaster, he rebranded himself Amen Ra, an Egyptian god.

He was a chiseled, tall, good-looking singer and dancer who was perpetually working on a new video or a new album, always chasing his dream of international fame. And then, in late 2020, he suddenly developed a strange skin condition that left him bleeding and in pain.

His family complains that his doctors were unable to diagnose what was wrong with him, and that they made mistakes prescribing him medicine. Stepniak’s mother, Tina Trozzo, a lawyer, is looking into filing a malpractice suit against Stepniak’s doctors, who took $400,000 out of him beyond what his insurance covered, she alleges.

It’s a shocking story of Hollywood striving gone wrong: Stepniak was killed by incompetent medical care in one of the wealthiest, most technologically advanced cities in the world, destroying the budding career of a future superstar who had just turned 30.

Except that’s not really the truth. The actual story is more interesting—and far more disturbing.

I got to know Kuba Ka and his mother Tina in 2017, when he announced on Twitter that he was ditching the Church of Scientology which, for a few months, had decided that Stepniak truly was about to become its new superstar celebrity.

Kuba Ka (everyone still calls him that, even after he changed it to Amen Ra) was much humbler and disarming than I expected him to be when we spent a couple of hours talking over Skype, and I came to like him much more than I expected to.

He had a childlike trust in other people, and seemed to genuinely believe that his art could help heal the world.

I also found it charming that he had run afoul of Scientology for asking impertinent questions. He was very impressed with David Miscavige, for example, the organization's ultimate leader. Most Scientologists, even those who are in the church for decades, never get a chance to meet Miscavige, but just weeks after Kuba Ka began his grooming as a church celebrity he met the man twice.

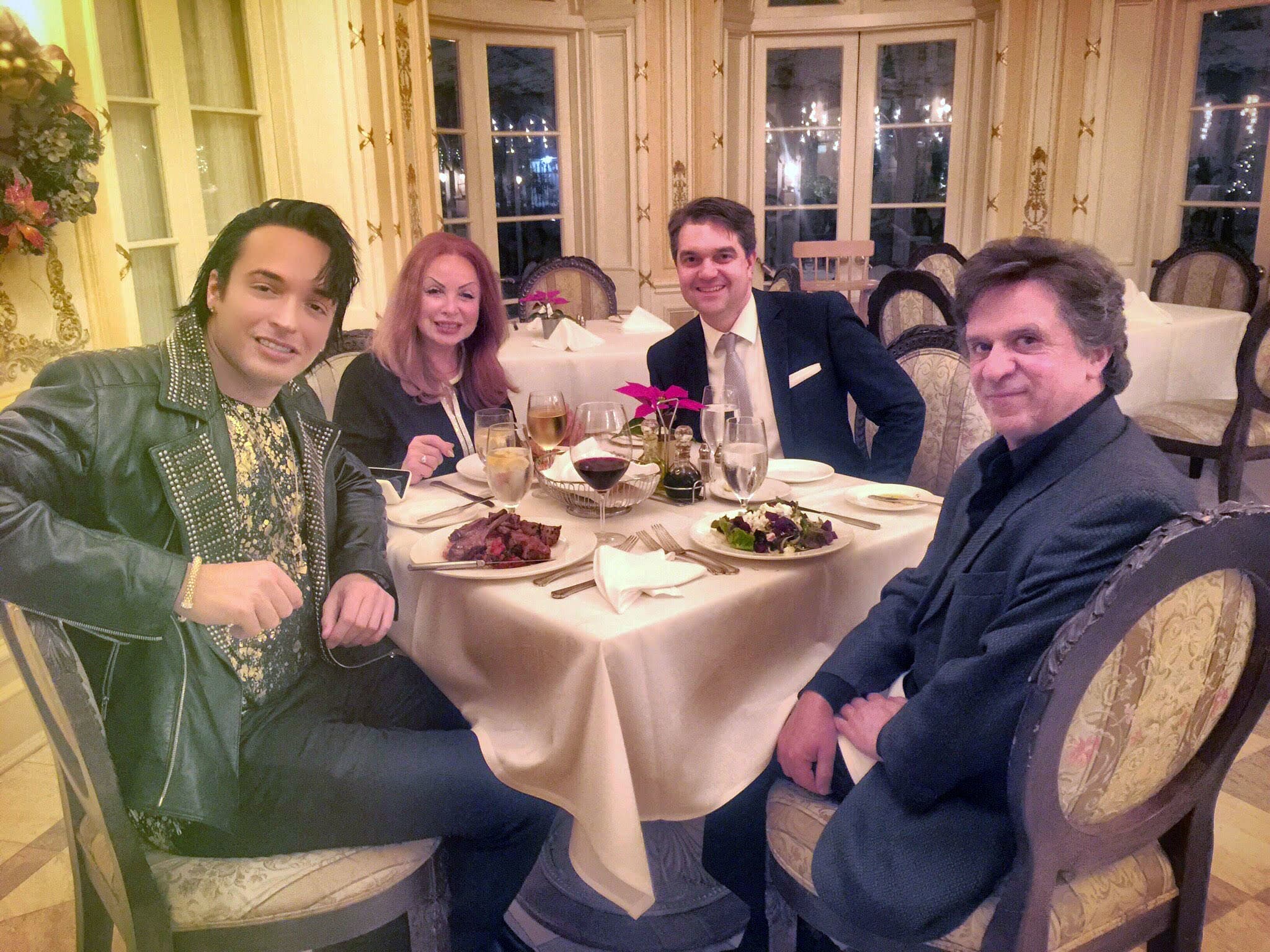

(L-R) Kuba Ka, his mother Tina Trozzo, Scientology handler Noah Bolduc, and Uncle Danny

Handout

When Kuba asked if he could read books written by Miscavige, he didn’t realize he’d committed a major faux pas. Scientology has millions of written words of books and policies, but it is all written by the founder, L. Ron Hubbard, who died in 1986. And although Miscavige has total control of the organization today, he would never dream of writing a new book of Scientology “technology” on his own.

For that and other transgressions, Kuba and the church found that they had irreconcilable differences. A big 26th birthday party for Kuba scheduled at the Hollywood Celebrity Centre for March 28, 2017, was canceled, and the singer took it so hard he was briefly hospitalized.

I mostly lost track of him at that point, but not before hearing that he’d decided he was now an Egyptian god named Amen Ra. His outfits became even more outlandish, his songs even more focused on his qualities as a deity.

But it was a shock to hear that he had died this past April, and so young. I reached out to Tina and was stunned by what she and Uncle Danny told me about Kuba’s final weeks.

And yet, what killed Kuba Ka was more chilling than even they seemed to realize. It wasn’t until I obtained the man’s medical records to confirm what the family only hinted at that I began to understand the true horror of Kuba’s end.

When I was originally researching Kuba Ka’s early life, finding it difficult to wade through the vast amount of mythology that Stepniak and his entertainment handlers had put out about him, I was fortunate to find that a Polish journalist, Borys Kossakowski, had written a thorough biography of Kuba for a Polish magazine in 2015.

Kossakowski is now finishing up a stint living in Seattle, and I called him to see if he had heard about Kuba’s death. He had, and was as stunned as I was.

In his 2015 magazine article, Kossakowski explained that Stepniak was from Gdansk and began making a name for himself in 2000, organizing charity concerts to benefit stray dogs and cats. (According to the claim in the Santa Barbara video that he was turning 25 in 2016, this would have made Stepniak only about 9 years old when he emerged as a party planner in Poland. It was Kossakowski’s article that first suggested Kuba Ka might not be as young as he claimed.)

Stepniak’s run of publicity in Poland ended in 2004, and he told Kossakowski, “I still feel pain. I cannot accept what happened in Poland.”

He explained that he had been inspired in part by Poland’s first lady at the time, attorney Jolanta Kwaśniewska, who had helped support his efforts. But then, he claimed, she had forced him to cancel a Christmas 2004 charity concert because it conflicted with one of her own events. She then supposedly told him, “You have no place in show business.”

That incident was so traumatizing, Stepniak said, he suffered from PTSD for years afterwards. In 2007, he moved to the U.S. and tried to start over, focusing on getting his body in shape as he grew into an adult. “To be honest, I still do not feel comfortable with myself,” he said. “I am constantly struggling with PTSD—fitness allows me not to invest energy in sadness, anger, and depression.”

Kossakowski asked him where the idea of declaring himself the “God of Pop” had come from. Stepniak replied that it had come from a conversation with Frank DiLeo, who had been Michael Jackson’s manager. (Kuba alleged that he had met Jackson himself in Poland, and that the singer had predicted big things for him.)

DiLeo managed Jackson from 1984 to 1989, through some of Jackson’s biggest successes. It was DiLeo, for example, who talked the Gloved One into making the Thriller video. DiLeo managed Jackson again briefly in 2009, just before the King of Pop’s death. But DiLeo may be even better remembered for his role as Tuddy Cicero in Martin Scorsese’s 1990 gangster classic GoodFellas, running the taxi stand for his older brother Paulie, played by Paul Sorvino. It’s DiLeo’s character Tuddy who, late in the film, shoots Joe Pesci.

Kuba Ka records his summer single “Sex In Rio” at EastWest Studios In Hollywood on July 7, 2015, in Los Angeles, California.

Araya Doheny/Getty

“It was like this: We were sitting with Frank DiLeo in the hotel. He said, ‘Kuba, I will make you a god.’ I liked it,” Stepniak told Kossakowski. Unfortunately for the Polish singer, DiLeo died in 2011 after that supposed conversation. But even so, most of the marketing of Kuba Ka tended to begin with the idea that he was chosen by DiLeo to be his next great project after Jackson.

In 2007, DiLeo was the subject of an artful profile by Nashville Scene writer Jack Silverman, himself a local musician. Silverman tells me today that in his later years, DiLeo was apt to take a run at unlikely projects.

“I can actually see him saying something like that,” Silverman says, when I asked him if DiLeo might actually have told an ambitious newcomer that he was going to make him a god.

But after DiLeo’s fatal heart attack, Kuba Ka would have to make it in Hollywood on his own.

Kuba’s career was supposedly saved by LaToya Jackson and then other managers as he crafted his Greek god persona and issued some records that got little notice.

His fame may have reached its high-water mark when he was featured on a short-lived reality series on the E! network called New Money that poked fun at people who had more ready cash than good taste. His episode aired on June 12, 2015, and featured him competing with two other “millionaires” for the title of that week’s tackiest spendthrift.

The opening lines of Kuba’s segment, showing him swimming in an indoor pool, capture the feel of it.

Show narrator: Behold, the eighth wonder of Vegas, Kuba Ka!

Kuba Ka: I’m Kuba Ka. I’m 17 and I live around the world. I’m a modern rock and roll gypsy.

Narrator: Seventeen? Hm. Math must be different in Poland.

Kuba: I’m like Poseidon, god of the seas.

Narrator: Whatever you say, you Greek, Polish, unusual person.

The show’s skepticism and mocking tone established from the start, Kuba is followed around his large hotel suite so he can show off numerous ridiculous props, including a crown he supposedly kept on a pillow on his bed ($12,000), the suite itself ($15,000 a night), and a metal breastplate he planned to wear on stage ($50,000).

It all comes off like a put-on that the show is thoroughly in cahoots with, including the next segment, when Kuba shows off his $7,000 Versace spike-studded codpiece to his manager—his mother Tina—who seems genuinely horrified that he’s planning to go on stage in the leather bikini bottoms and chaps.

“But it is even not sexy!” she blurts out in her rather charming accented English.

The next time we see him, Kuba has swapped out the spiked underwear for red undies that have a definite Sean Connery-in-Zardoz flavor, and he’s being wired up for a stage show that will see him levitating above a collection of scantily clad dancers.

What follows is a performance that the word “cringe” only begins to describe, as Kuba “sings” the lyrics of a song which don’t seem to go much beyond “Here we go!” as he “dances” in the limited way one could while strapped to a wired harness. The camera also briefly captures the crowd, which is sparse.

At the climax of this train wreck, a small eruption of sparks emanates suddenly from the center of Kuba’s breastplate.

Narrator: Kuba’s fans go wild. Both of them.

Kuba Ka: Thank you so much!

At the end of the episode, the narrator announces that second place goes to the woman of sudden wealth whose shopping sprees clean out entire furniture stores, and this week’s first prize is won by a flamboyant Hollywood clothes designer who spends tens of thousands on attire for the family pooch and whose boyfriend proposes to him on camera.

Kuba Ka had placed third out of three.

By the time I talked with Kuba in 2017, he had spent a decade in Hollywood chasing immortality, but what drew me to him was that for a short time the Church of Scientology actually appeared to buy into his dream.

In a two-hour Skype session, I talked with Kuba, Tina, Uncle Danny, and two of Kuba’s entertainment handlers, Vikki Lizzi and MJ Lord.

The first thing I noticed was that Kuba turned out to be surprisingly humble for someone who referred to himself unironically as the God of Pop, and he was too polite to interrupt Tina, who kept jumping in to add details from her perspective not only as his mother but also as an attorney who was very protective of her only child.

We went over his background, his charity shows in Poland and his later encounter with DiLeo, and then I asked him how, after several years making records in Hollywood, he had gotten involved with Scientology.

He explained that he was becoming increasingly unhappy with the way young talent was treated in Hollywood. “They were selling me for photo shoots. I felt like a piece of meat,” he said. “They would say, if you won’t undress we’ll send you back home to Poland.”

He said he would hear things about Scientology, that it had a reputation for being drug-free and generally opposed to Hollywood’s seamier side.

Kuba Ka appears during the filming of E! Channel's New Money TV series at the Westgate Las Vegas Resort and Casino on June 12, 2015, in Las Vegas, Nevada.

Bryan Steffy/Getty

“When I finally went there, I was the happiest person,” he said. And at first, so much about it seemed to resonate with his own personal interests, as he was given an “amazing” welcome. “They told me they could help with all of my dreams.” And he described being treated like royalty right away.

But I wondered how Scientology would know to treat him like a celebrity when he wasn’t really well known. And he explained that there was a middleman, a film producer who worked at Variety magazine. (The producer, who worked on promotions at the magazine, didn’t respond to my inquiries about why he was funneling people to Scientology’s Celebrity Centre.)

After that introduction, a Scientology handler named Noah Bolduc was assigned to Kuba and became their constant companion at the church.

“I was a little bit surprised that Kuba wanted to be part of this church,” Tina said. “But he was no longer a little boy and deserves his freedom. My son’s dreams are bigger than life.”

But as the love-bombing went on, Kuba’s business partners became increasingly suspicious.

“I was suspicious that they were putting so much into him. I thought there had to be an ulterior motive,” said MJ Powers. And Vikki Lizzi had her own reasons for being wary of Scientology after the experiences of her boyfriend, actor Jeff Conaway, who had died in 2011.

“They need someone young,” Vikki piped up, and there was some truth to that. Some of Scientology’s celebrities are getting rather long in the tooth.

“They wanted to groom my stardom,” Kuba said.

The rest of them were also pressured to take courses along with Kuba, and to start paying large sums of money to the church, which they resisted.

Meanwhile, even at only an introductory level, Kuba Ka was getting some pretty amazing treatment and special access. Within only a few weeks, for example, he got to meet someone most Scientologists never do: church leader David Miscavige.

“It was the closest thing that came to meeting Michael Jackson,” he said. “I never met someone who was so powerful. It was like meeting an emperor or the Pope.”

I asked Kuba about what Vikki had said—that he had also had a chance to meet John Travolta, but he had been told it would only be in private in a secret room at the Celebrity Centre. Kuba smiled, but said he probably shouldn’t say anything publicly. So we moved on.

Kuba said things started to get a little uncomfortable as his 26th birthday was approaching in March 2017, and he and his family and friends began planning their big charity event at the Celebrity Centre that was to become his big coming-out as Scientology’s new star.

The invitation for Kuba Ka’s 26th birthday party at Scientology’s Celebrity Centre

Handout

Kuba, it turned out, had ideas about how Scientology might make some improvements, and it didn’t go over well.

“I told him that some of the courses should be free, or people could donate what they wanted, even if it was only a dollar. That’s how you bring in the homeless and other people who are in need,” he said. “And that’s when they started not to like what I was saying. I thought it should be like bringing people to a temple where everyone is welcome. I could see that wasn’t the case, and it was very painful for me. It’s not what I believe in. I want to do things for other people.” (The Church of Scientology did not respond to requests for comment.)

Meanwhile, he said, the early honeymoon was over and he was being told about more and more rules that he had to abide by if he wanted to move up Scientology’s ranks.

“I told them I loved their mythology, but I wasn’t really doing this for spiritual reasons. I think they misunderstood that. They wanted access to my bank account and my medical records. They said I needed to trust them.”

“I tried to warn him,” Uncle Danny interjected. “I took one course from them 33 years ago. I knew who they were and I tried to warn Kuba. They’re still sending me fliers 33 years later!”

Kuba also had ideas about how to counter Scientology’s terrible reputation in the media. “I told them, you can’t just reject Leah Remini, you should talk to her. I wanted to invite her to the event.”

Invite Leah Remini? To the Celebrity Centre?

“I said to Noah, please arrange a meeting with David Miscavige so I could give him suggestions for these changes,” he said. And that’s when he started to hear that he was becoming a problem.

“Noah said that Joy Villa had made a report on me, and that she said I was trying to be a Trojan Horse to destroy the church,” he said.

Joy Villa was also an aspiring performer who had been working her way through Scientology for a few years. At some point, she introduced herself to Kuba at the Celebrity Centre and took a selfie with him.

Kuba Ka and Joy Villa

Handout

Later, he said he met with Joy and her publicist, and Kuba suggested that to expand Scientology’s reach, they should go to Washington, D.C. and try to meet the new president. (“I don’t actually support Trump. I just mean we should try to meet with him because he’s the president. I don’t support anybody. I only support the United Nations and Queen Elizabeth,” Kuba added with a laugh.)

“I had told her and her publicist that Scientology was too much behind closed gates. Let’s show the love and bring in the media, bring in Leah Remini. And after I told them that, Joy and her publicist told me they couldn’t be around me because I was too controversial and was talking about reaching out to Trump. Then she turned around and supported Trump!”

Kuba believed that his suggestion was the seed that motivated Joy to wear a “Make America Great Again” dress to the 2017 Grammy Awards ceremony, which instantly made her famous with Trump supporters. She turned it into multiple trips to the White House, an exploratory look at running for Congress, and she continues to work her fame with conservatives on the book and lecture circuit. (She didn’t respond when I tried to ask her about Kuba’s claim that he gave her the idea of supporting Trump for attention to benefit Scientology.)

As the March 2017 party approached, Kuba and Joy were talking about writing a song together that would benefit human rights, he said. And for the charity ball itself, Kuba had talked to Joy about performing one of the songs from his new album with him.

But then he learned from Bolduc that she had submitted a “Knowledge Report” on him. “Joy opened our eyes on who you are, they said.”

“They put him through lie-detector tests. It was awful,” Vikki alleged.

After months of planning, the Scientologists shocked them by saying that such events didn’t take place at the Celebrity Centre, and it was canceled.

“Could this organization really have no empathy?” Kuba asked me. Both he and Vikki said they had been followed in the last few days—Kuba recognized his stalker, who he had seen working security at the Celebrity Centre. They asked us what Scientology was capable of. Were they in danger?

Soon after our conversation, Kuba Ka was briefly hospitalized for nervous exhaustion. The Scientology episode had left him an emotional wreck.

I then heard from his cousin Patrick, who sent out emails for the family “empire,” that the Kuba Ka name had been retired, and that we should now refer to him as Amen Ra.

Amen Ra

Handout

Stepniak had traded in one pantheon for another.

Tina Trozzo says that the pandemic was especially hard on her son. His career, which included collaborating with musicians and making appearances at public events, came to a standstill, as it did for so many other people.

But the pandemic had also arrived just a few months after another shock in their lives: The death of Kuba’s father Andrzej of a heart attack on Dec. 19, 2019, at the age of 67.

Kuba, an only child, had been particularly close with his parents, and Andrzej often showed up in his videos. His sudden death was an unexpected blow.

As the pandemic dragged on through 2020, Kuba, now restyled Amen Ra, focused on a new album that would, once and for all, give him the success he craved. He called it Creation, and put together several different teaser videos that were posted to his YouTube channel in June.

Then, postings to the channel stopped. And on Oct. 17, Tina says, the illness arrived.

There was something wrong with Kuba’s skin—particularly his face, but also on his arms, legs, and torso.

It frightened and confused them, Tina and Uncle Danny tell me, and doctors seemed unable to figure out what was causing it.

Kuba's face, which had been, along with his washboard stomach, his trademark feature, was suddenly erupting in open, bleeding sores.

After years of trading on his looks (and complaining that it was all that Hollywood cared about), Kuba’s beauty was suddenly under attack from a horrifying, mysterious ailment.

Sores opened up on other sores until Kuba’s cheeks became one large black mass of scab, blood, and pus. Similar patches of open gore were appearing on his arms and legs.

Uncle Danny, who was staying with Kuba at his Olive Street apartment in Downtown L.A., said that it wasn’t just that his skin was under attack, but that he was suffering from prolonged infections and inflammation. Bleeding and in intense pain, Kuba was weakening as his doctors tried to find out what was happening.

“He did five different biopsies, and no diagnosis. But he was bleeding a lot and discharge was coming out of his face and body,” Uncle Danny says.

“Uncle,” I learned, was an honorific. Maghen had met the family in 2011 and had quickly become very close.

“He was thanking me and his mother all the time for helping him. I spent five and a half months at his apartment. He was the kindest person I had ever known. I never heard him use any bad words,” Danny says. “Tina was in Europe. His friends had left. I was driving him to the doctor’s and taking care of him. He was very kind to me always. COVID was terrible around us those days. He was alone.”

Then, in February, Kuba made another video.

He titled it “Face Jihad,” and even at just a little more than a minute it’s extremely difficult to watch. It features blood spurting from his face, flashes of his huge scabs, and pools of blood on the tiles by his feet.

WARNING: Incredibly Graphic Footage

In the video, Kuba claims that he is the victim of Neglected Tropical Disease, and that he is producing a documentary about it. Uncle Danny, who also ascribed to the NTD diagnosis, told me that they believed that when Kuba was in his teens, he had gone to Africa to produce charity shows, and that he must have been infected with a parasite there.

Kuba then squeezes his nose with his fingers and a river of blood spurts out on the camera lens. But it was parasites that were causing it, his family believes.

It certainly seemed, in a strange way, to fit the Kuba Ka mythology. He had chased immortality as a god of entertainment in Hollywood with his beauty and talent, but there was always something from back there—whether in Poland or, in this new version, in Africa—that was stealing from him what he was due.

Tina, describing her son’s ordeal, then told me something that startled me, and Uncle Danny confirmed it. They both said that Kuba was angry when his primary treating physician revealed his diagnosis: mental illness.

The family still refuses to believe it, insisting that Kuba must have been suffering from a tropical disease he picked up in Africa.

But the horrific truth was all too obvious, given his doctor’s diagnosis.

Kuba Ka was finally and forever ending his exhausting chase of fame by ripping apart his own face.

As the spring arrived, Kuba was losing his battle to the thing consuming his skin.

“He became very weak. He wasn’t able to walk in his last days. He suffered from a huge amount of pain. The inflammation was in all of his body,” Kuba’s mother, Tina Trozzo, says.

“He was trying till the end of his life to be a fighter. He was getting ready to fly to Mass General Hospital in Boston,” she adds.

Her husband had worked there as a visiting professor a few years before his death, and she still had connections there. Kuba was scheduled to fly on Sunday, April 25.

“He wanted to live and be safe. Kuba was fighting for his life with true power. He had big plans for his life,” Danny explains.

Kuba Ka poses at The Plaza Hotel on July 24, 2015, in New York City.

Robin Marchant/Getty

Kuba’s family continues to insist that his doctors could never properly diagnose his skin problem, and that their medications killed him.

That second assertion may certainly be the case. Tina not only turned over Kuba’s detailed autopsy report to me, but also the final pain medicine prescription that he received on April 22, the day before he died.

The autopsy revealed that Jakub Stepniak, aged not 23 (according to his E! network claim) or 30 (based on what he told me in 2017) but actually 35, had died of “methadone toxicity.” There was no evidence of a parasite or other neglected tropical disease.

He’d simply overdosed on pain medicine in what the medical examiner determined to be an accident.

I sent both documents to Andrew Kolodny, a national expert on the opioid crisis and the medical director of Opioid Policy Research at the Heller School for Social Policy and Management at Brandeis University.

(The prescription listed Kuba’s age as 41, but his mother Tina assures me that’s a mistake and that he was born in 1986, not 1980.)

Kolodny examined the prescription and explained to me that Stepniak had received both methadone and another powerful opioid for pain, a combination of hydrocodone and acetaminophen known commonly as “Norco.”

I described to him what the family had told me about the doctor’s diagnosis, and Kolodny said that “neurotic excoriation” was not an uncommon affliction, particularly for drug abusers who picked at their skin. (Kuba, however, had never been a drug abuser or a drinker, as far as I knew.)

As for the doses of pain medicine, he said they were surprisingly strong.

“Unless he was someone with a very high tolerance for opioids, these are very high doses,” he says. “Opioids are not good drugs for chronic pain.”

In the era of opioid overprescribing, it was an all-too-common death—a 35-year-old taking too much pain medicine he had legally been given.

Kuba Ka, the God of Pop, was a mere mortal.

Tina Trozzo held a funeral for her son at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Hollywood Hills on May 13.

Since then, she has continued to post images to her Facebook account of her husband who died in 2019, Andrzej, and her son Jakub from the various stages of his career, from the young Polish charity fundraiser, to Kuba Ka the God of Pop, to his final manifestation, Amen Ra.

“Forever alive in my heart,” she says about the both of them.

When I called Borys Kossakowski last week, he said that in retrospect, he didn’t believe Kuba’s story about the wife of the Polish president supposedly causing his PTSD. “It’s hard to believe that she could actually be an enemy for him, or act like that. But who knows what happened. And who knows what happened with the money,” he says, referring to the charity events in Poland that made Kuba briefly famous.

“People there had started to realize that it wasn’t about the charity work, but about the creation of the persona of Kuba Stepniak,” he says. “My feeling was that he was very narcissistic, very focused on himself. And he considered any kind of criticism as an open act of aggression on him. It was him against the world. You could be his follower or his enemy. There was nothing in between.”

But he added that Stepniak really was very well known in Poland. He had become a big star there as a very young man.

Kossakowski says he isn’t sure why Kuba decided to grant him the 2015 interview. He was the first Polish journalist Kuba talked to after moving to the U.S. “He said how badly he had been treated, how the journalists in Poland hated him. But that wasn’t realistic.”

In a video he made last year lauding the Black Lives Matter movement, Kuba said that BLM’s struggles reminded him of his own in Poland, and he briefly flashed on the screen a description of a criminal incident.

Kossakowski said it was a reference to a mugging. Kuba had been attacked in 2001 by three men who roughed him up. In the video, Kuba says this is the source of his PTSD, not the incident with the president’s wife.

Either way, Kossakowski believes that Kuba’s mythmaking about whatever had wrecked his life in Poland was a story to cover up how his real struggles were in the U.S.

“I think he’s a victim of this American thinking that you can be whoever you want. He really pushed this to the limit. He really wanted to be the God of Pop, and he didn’t want to have any contact with reality.”