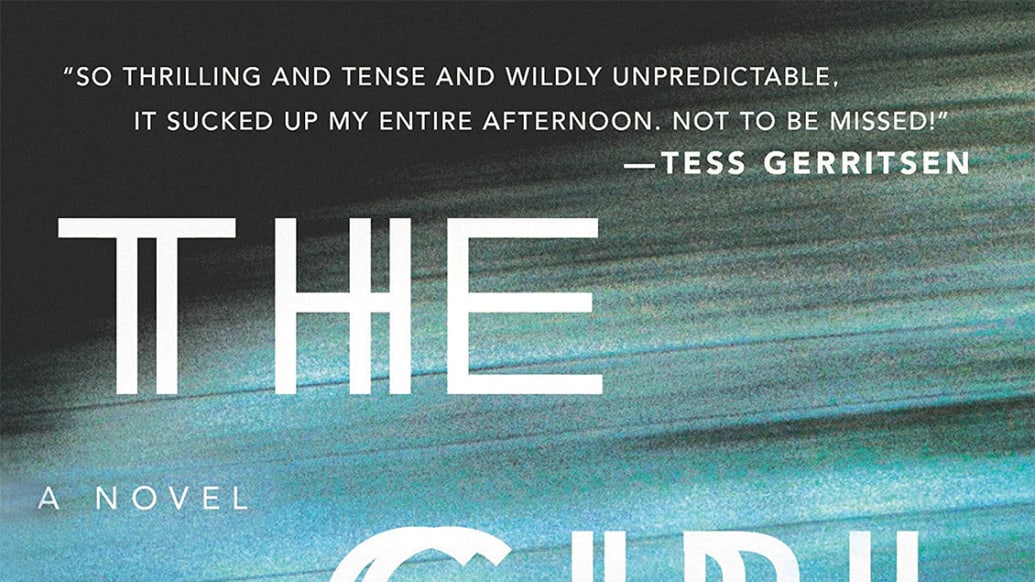

What do Gywneth Paltrow, Stephen King, and Reese Witherspoon have in common? They are all big fans of the newest thriller dominating bestseller lists, Paula Hawkins’s The Girl on the Train.

The novel tells the story of Rachel, an alcoholic divorcee who creates an imaginary life for the couple living in a house she passes every day on the train—a house in which she may or may not have seen something nefarious happen. It is a finely wrought tale as a thriller, but Hawkins also is adept at observing many of the silent tragedies of modern life—the permanence of drunk emails, the overbearing quality to our “understanding” of alcoholism.

There are thousands upon thousands of books published every year, and when a debut novel like The Girl on the Train breaks through, it’s always interesting to try to figure out why.

The thriller has dominated The New York Times bestseller list for nearly four months since its release. According to Riverhead, the book’s U.S. publisher, it recently passed 1.5 million copies sold, which might just make it the fastest selling hardcover adult novel ever.

“Honestly, it’s a constellation of a lot of different things,” explains Jynne Martin, the publicity director for Riverhead. There were rave reviews from critics (ranging from Us Weekly to The New York Times), spillover excitement from the Gone Girl movie, and a concerted push by the whole Penguin Random House operation.

What was most interesting was the power of Goodreads, the “social cataloging website” owned by Amazon. Throughout the fall, in the run-up to the books release, Riverhead did a significant number of giveaways, and strong word of mouth led to the book being added to people’s shelves on Goodreads at an astounding rate.

Of course, it doesn’t hurt to have good material to work with. We caught up with the book’s author, Paula Hawkins, and discussed everything from her newfound fame to being creepy as a writer and her literary journey.

The Daily Beast: Why do you think this book has resonated so much?

Paula Hawkins: It’s a difficult thing to say. There are certain things about the story that I think are universally recognizable. The sort of enjoyment that we all get from that voyeuristic impulse of looking into other people’s house as we pass them and the idea that there might be something sinister or strange going on in the houses we pass every day or in our neighborhood, is a very compelling idea. So I think that’s one thing people have latched on to. There are also some strong voices in there that readers have responded to. I also have to say that the publishers, both in the U.S. and U.K., did a fantastic job of getting people talking about it on social media and getting lots of reviewers interested.

I hesitate to call it this, but there has also been a “trend” of female thriller novelists, right?

I guess you have trends in publishing, don’t you? As you say, it’s insane to lump everyone together, but they do, and they talk about as though it were a genre of its own. There seem [to be] good female writers who are writing about this domestic noir type crime novel where it’s not about serial killers or spies, it’s very much the dangers that surround us in our homes, from our relationships. So it fits into that sort of trend, but I’m always at pains to point out that when you’re writing a book, when you’re starting a book, you’re not aware that you’re going to be writing within a particular bit. That’s just not how you think about it. You have a story that you want to tell, and it happens to fit into that area of the market. There are also, I like to think, echoes of Hitchcock and that paranoia and suspense. There are other cultural touchpoints that we can identify it with as well.

The chilling element is that the danger is in your home.

I think that for me that’s much more terrifying. Most of us aren’t likely to come across a spy or get ourselves involved in political intrigue or, hopefully, meet up with a psychopath. The dangers that are close to home are all the more terrifying.

You have the main character, Rachel, who sits on these trains and imagines these lives for a house that she passes by. Where is the line between imaginative and creepy?

Well, Rachel’s quite a particular sort of person isn’t she? She’s got her own problems. Because of the situation in which she finds herself, because her relationship with her husband has broken down, and she’s feeling very lonely, she’s desperate to make a connection. I think that’s where the line gets crossed. I think this happens to lonely people—you’re so desperate to make a connection you start imagining relationships where none exist. That’s where you become a creepy, stalker-ish person. She’s sort of conscious that she’s doing it, but she can’t quite stop herself because of her general loneliness and her depression.

I remember reading my first rape scene in a book, I think it was Ken Follett, and thinking he must have been embarrassed when writing this. Do you ever feel embarrassed by what you’re able to imagine?

There are often moments when you think, “Oh God, my mother is going to read this!” But you can’t censor yourself. But yes, I sometimes I do think, “Where did this come from? Why have I got such a horrible imagination?” Because I’ve had a good life, I shouldn’t be able to come up with these terrible things but I do. So yes, it is worrying.

In the stories about the success of this book, your early career as a writer has been brought up—your financial advice book Financial Goddess and the Amy Silver novels. How did that shape your writing?

The journalism, I was a financial journalist, it’s very good training as a writer. You have to write for deadlines, you have a certain economy of phrasing. As a training ground as a writer it’s fantastic. I also think it teaches you to be observant, to listen to people, and gives you an ear of dialogue from doing interviews. Then the Amy Silver novels were commissioned. I was given the idea by someone else. They were really fantastic as a learning experience for a fiction writer. I really got to flex my fiction muscles and try things out, play around with structures. So by the time I got to this book, which really came from me and was all my own ideas and what I wanted to do, I had an idea in my head how I wanted to structure things and how I was going to pace things, and what might work and what might not. It was a really good instruction into writing.

One of the issues the book raises is the difficulty of taking responsibility for things if you can’t remember them. How did you come to that idea?

I’ve had conversations with people who have had blackouts from drinking. There is a sense in which, while they feel remorse, it’s difficult to connect the remorse to the event if you don’t actually have a memory of the event. You know you’ve done something wrong, but I think you can’t quite feel the same level of responsibility if you don’t actually remember performing the action. So it’s a really weird situation in which you know that you were at fault, and you ought to apologize for it but there’s a gap, there’s a disconnect there which I think is really strange and fascinating.

Despite how much has changed over the past century, what also hangs over the novel is that women can’t escape the pressure to have children.

Absolutely. Some people have commented that the women in this book all seem to be focused on this. I think there’s a certain time in your life, your late 20s, early 30s, where suddenly lots of your friends have children, and it becomes an issue, an issue for your relationships, an issue in regards to you career. People start asking you about it. It suddenly seems to become all-encompassing. That’s something I don’t think we can get away from. That’s just the way our society is, and we are always going to have children, it’s always going to be an issue. I do think it becomes all-encompassing at one point in our life. Then obviously the pressure goes away and we make our choices. We make those choices and they are judged and interpreted in quite a public way, as though they belong to everyone and not just to you.

I’ve got to say as somebody who once lived directly above a subway stop, it was pretty interesting to see somebody romanticize living by the railroad tracks.

Well, that’s partly because I’ve not actually done that. I’ve never lived that close to the train like that. I can imagine that I would like it.

The book has been optioned by Dreamworks. I couldn’t help but see Rachel as this Bridget Jones gone wrong. Have you thought about who might play other characters in the novel?

I’m very bad at casting because I keep changing my mind about who would fit. I keep watching TV, and thinking, “Oh, she’d be all right, she’d be good.”

You’re also working on a new novel, correct?

I’m writing at the moment, and hoping to finish over the summer so that it hopefully will be out summer or autumn of next year. It’s also a psychological thriller. It also deals quite a lot with memory issues, but in a different way. It’s about the memories we have from childhood and how the stories that we tell about ourselves and our families shape who we are. It’s about how our memories from childhood can be quite flawed. What one sibling might remember in an incident is very different from another one. And yet those incidents go to make up your personality.

Do you feel pressure given the success of Girl on the Train?

Yes, when I wrote the last one nobody knew who I was, so you’ve got more freedom. Now that I know there are a lot of readers who’ve enjoyed this book and will be looking forward to it. So, yes, there is pressure. So I am quite nervous about it, but you’ve got to just put that aside. I don’t want to leave too big a gap between the first book and the second, because the longer that gap, the more terrifying the publication of the second book becomes.

You were unknown before the book come out, now with its success have you been recognized on the street yet?

No, no, nothing like that yet.

When did you realize that this book, and you, were going to become famous?

Well, obviously my name is known now, but I don’t think people generally tend to recognize authors very much. People like J.K Rowling maybe, Gillian Flynn might be recognized, but I reckon she could walk by me on the street and I wouldn’t know who she was. So I’m not sure it’s that kind of fame. I suppose when I realized it was doing really well in the States, that was terrifying because of the number of people you’re talking about because it’s such a big place, you’re suddenly talking millions. That’s probably the moment when I thought, “Oh God, this is sort of scary now.”