The Mafia is dead. A New York jury said so just this week. A trial in federal court of two men charged with racketeering and conspiracy to commit extortion ended in a verdict of not guilty. Defense attorneys for the two men had argued that the Mafia was destroyed decades ago and that their clients were being unfairly profiled as gangsters because of their Italian ethnicity. The defendants walked.

Long live the Mafia: the day after that jury verdict, a Gambino family mob boss was gunned down in his own driveway on Staten Island, in what history will record as the first gangland slaying ever recorded on video. So maybe the death of organized crime is slightly exaggerated.

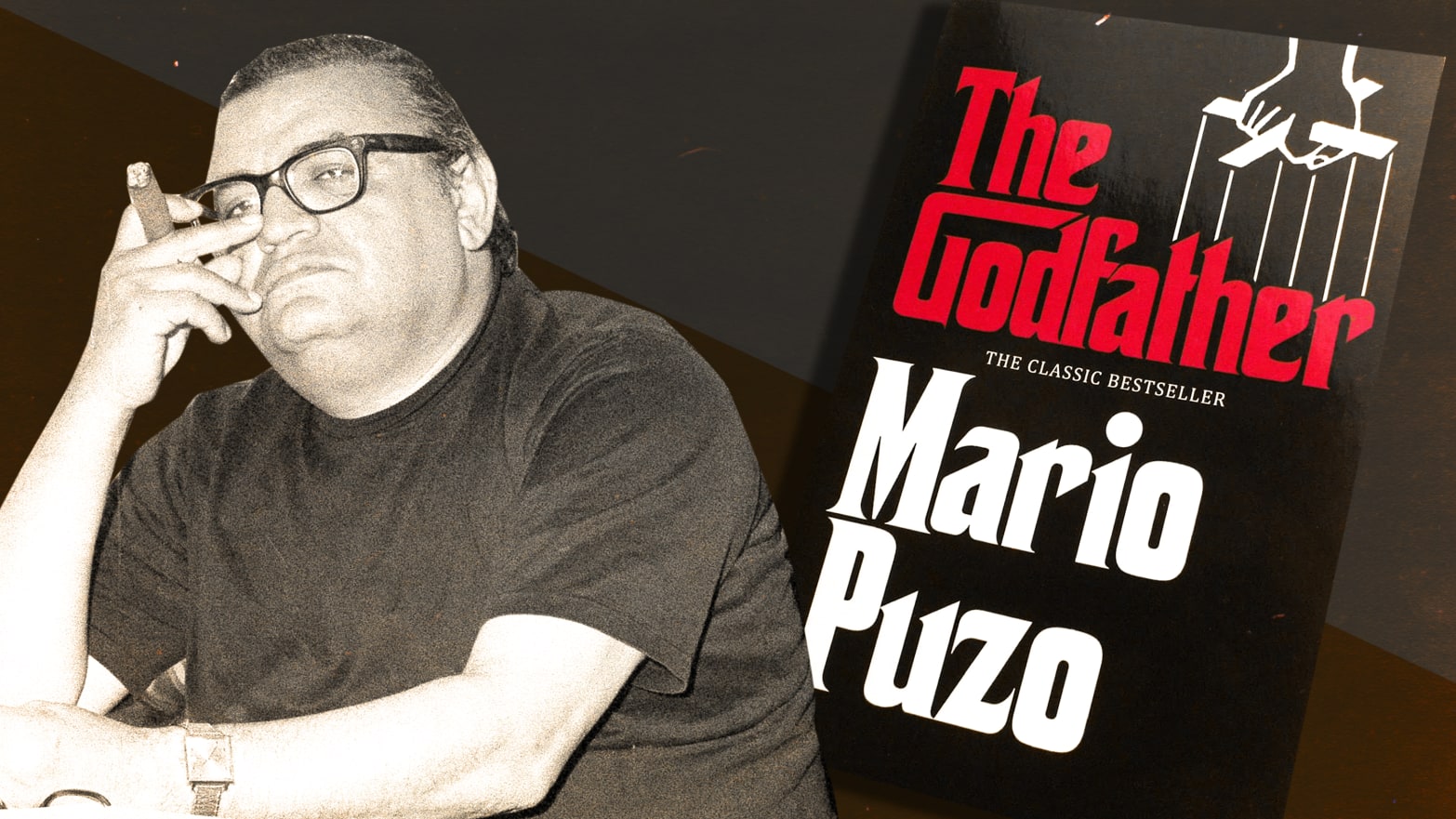

In a strange coincidence, amid all this fresh news about the Mafia splattered across the tabloids, Mario Puzo’s novel The Godfather turns 50 this month. And here’s a certainty: while we can debate the actual Mafia’s state of health all day long, it is still very much alive and well in the pages of Puzo’s novel—maybe because no one ever accused him of writing realism.

Never out of print for half a century, The Godfather is a durable novel. Which is not to say it’s flawless. Far from it. To put it as politely as possible—who wants to throw shade on a birthday party?—Puzo wrote a good novel, and somewhere inside that novel is a magnificent story.

Anyone who knows the movie and then reads the book is going to become impatient because the movie is the greater work. The plot is more focused, the characters more crisply drawn, the dialogue sharper. When Puzo and movie director Francis Ford Coppola wrote the screenplay, they cut away everything extraneous, paring the story to its essence: a majestic, timeless tale of an aging king with three sons.

You can credit Coppola with this, if you like. But that slights Puzo twice over. First of all, the original story, flawed or not, is all his. The novel rode the bestseller lists for months because Puzo wrote a page-turner about the Mafia. Second, Puzo’s contributions to the screenplay were considerable.

In a short foreword to his father’s novel, Anthony Puzo points out that in an early version of the screenplay, Coppola refers to Clemenza browning meat in a skillet. Mario Puzo scribbled on the draft, “Gangsters don’t brown. Gangsters fry.” Now, if you compare the novel to the screenplay, you discover something else. There’s no dialogue in that moment in the book. Clemenza is cooking spaghetti for his crew in the Corleone kitchen. In the screenplay, he invites Michael to learn how to cook for 20 men, and then proceeds to do a running commentary on his actions, right down to “frying” meatballs. So the scene becomes much more vivid and funny in the movie because of what he says—but both creators had a hand in that.

I’m sure they teach The Godfather screenplay in film schools, but I hope they teach it—specifically, a novel to screenplay comparison—in fiction writing workshops as well. There is no better lesson in how to find the heart of a story.

The novel’s Johnny Fontane subplot disappears almost entirely from the movie script, and rightly. It adds nothing to the core story. (For that matter, it not only adds nothing to the novel but actually detracts—the chapter about a woman getting her vagina surgically tightened is so extraneous that you wonder what editor dozed through this section when readying the original manuscript for publication.) Other scenes are combined or compressed, and much of Vito Corleone’s back story is excised (though revived for The Godfather Part II). Some of the catchphrases appear in both book and movie, but the movie highlights them better—the jewels get better settings. Maybe this is Coppola’s doing, but it’s worth noting that the memorable quotes originated, according to Puzo, with his mother. Vito Corleone may have been loosely based on mobster Frank Costello, but “Keep your friends close and your enemies closer” and all the rest were household refrains Puzo heard growing up.

Nearly every scene in the movie can be found in the book in one shape or another. The big exception, and it’s very big, is the scene near the end of the film where Vito and Michael are alone together in the backyard, when the father warns his son that he will be killed at a supposed peace conference and that the person who brings the message will be a close associate turned traitor. That entire scene was ghosted by an uncredited Robert Towne, and it crystallizes the tragedy of Michael’s inexorable involvement in the family business. Another crucial little addition: after Michael tells Kay about Luca Brasi at the wedding of his sister near the beginning of the movie, he says, “That’s my family, Kay. It’s not me.” That’s not in the novel either.

In his brief but very generous introduction to the 50th anniversary edition of the book, Coppola compares the making of the movie to capturing “lightning in a bottle.” Exactly. There are great directors, Coppola among them, who make movies that only they could make, but goodness knows he had lots of help with this one. Try imagining The Godfather without Nino Rota’s soundtrack, or Gordon Willis’ photography, or anyone else playing those characters (the fact that they considered Ernest Borgnine for Brando’s role still makes my flesh creep). Everything and everyone came together perfectly.

But before all that could happen, there had to be a story first, and so we pay homage to Mario Puzo. Without him, the gangster story would not, as many have observed, replace the western as America’s go-to myth. We would not have, “Make him an offer he can’t refuse,” and all those other catchphrases that litter our conversation and discourse. We might never have known that a Sicilian cannot refuse a request on his daughter’s wedding day, and we surely would never look at our families and wonder, who’s the Fredo?

Ultimately it does not matter that The Godfather was a big mess of a book, or that Puzo had grandiloquent notions of his own greatness as an artist (the novelist Joy Williams nailed his pretensions good and hard in Esquire). What matters is that the book exists at all. And that Puzo, when he had the chance to collaborate with Coppola and retell his novel as a movie that was better in almost every way, accepted the challenge, not once but twice. OK, the third time was not at all charming, but nobody’s perfect.