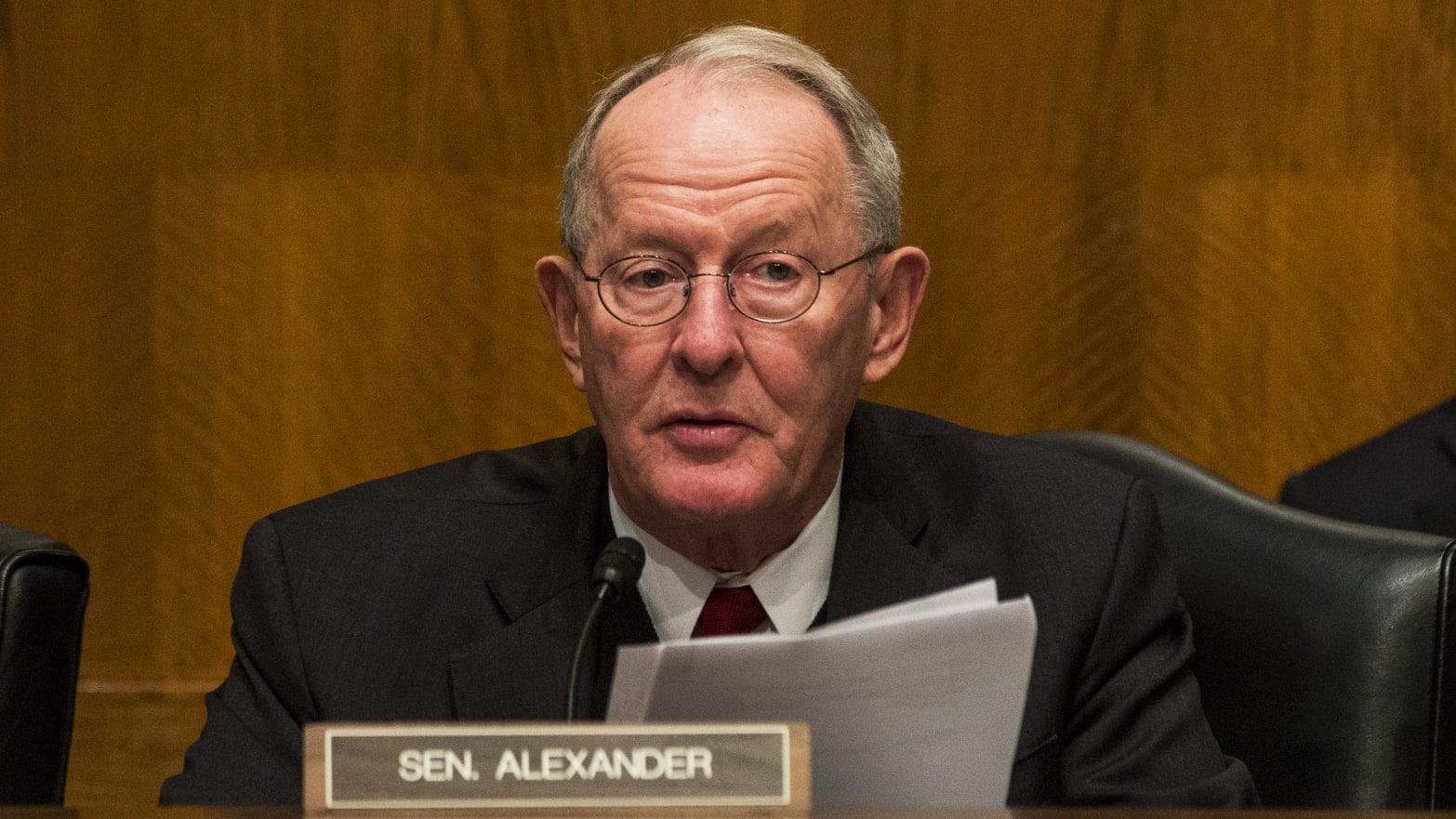

In 1967, Lamar Alexander came to Washington from his native Tennessee to serve as an aide to Howard Baker, the Republican senator from his home state who later helped to expose the White House tapes that sealed President Richard Nixon’s fate. Alexander is now concluding his career as Baker’s successor in the Senate by aiding President Donald Trump in hiding damning evidence of what the senator himself described as a scheme to “undermine” confidence in the principle of equal justice under law.

Furthermore, Alexander allowed other Republican Senators to borrow his own long-cherished reputation for probity and fairness as a cover for their near party-line vote in favor of a sham trial of Trump, without any witnesses.

Just weeks ago, Alexander promised that the Senate’s trial would meet a higher standard than the House impeachment proceedings, which he decried as a “circus.” He vowed to “study the record” to determine “whether we need additional evidence.” But at 11 p.m. last night, Alexander declared that the Senate did not need to obtain any additional testimony, because the House had actually done a phenomenal job.

Alexander insisted that it would be a waste of time for the Senate to hear John Bolton testify to Trump’s scheme to coerce Ukraine to manufacture defamations against Joe Biden, because the nation already knows that, as the senator bluntly put it, the “president did it.” We know this, Alexander continued, because the House managers came forward with a “mountain of overwhelming evidence” establishing that Trump engaged in the very conduct alleged in the House’s First Article of Impeachment, for abuse of power.

Indeed, Alexander echoed Chairman Adam Schiff by saying that the House managers had amply proved that Trump pursued a scheme to “pressure Ukraine to investigate the Bidens.” And Alexander scorned Trump’s conduct, stating that, “[w]hen elected officials inappropriately interfere with . . . investigations [of their political opponents], it undermines the principle of equal justice under the law.”

Yet while he made a compelling argument for Trump’s culpability, Alexander also unconvincingly asserted that Trump’s manifest culpability actually provided his reason to avoid hearing further evidence of his grievous misconduct. There’s “no need,” Alexander said, “for more evidence to prove something that has already been proven.”

Thus, in a matter of days, Alexander pivoted from claiming that the House had engaged in a deficient, “circus”-like investigation, to asserting that the House had assembled a case that was so ironclad it could not be improved by further evidence.

Alexander’s bizarre claim that the very success of the House inquiry mandated the rejection of the managers’ request to hear Bolton’s testimony was accompanied by an equally strange account of the constitutional standard for impeachment.

Even as he acknowledged that Trump’s coercion scheme “undermined” a foundational constitutional “principle,” Alexander asserted that such grave presidential misconduct somehow fails to meet the “United States Constitution’s high bar for an impeachable offense.” Alexander did not even attempt to explain what that supposed “bar” is, let alone why the grievous misconduct he said was proven by the House’s “mountain” of evidence failed to meet it.

While Alexander could not cogently explain why undermining the Constitution is not impeachable, he did indicate a personal preference for allowing voters to pass their own judgment on the President’s misconduct, stating that the “American people should decide what to do about what [Trump] did” in the upcoming election.

Other Republican senators seemed attracted by Alexander’s rhetoric, and echoed it today before joining him to vote in favor of a sham trial that will inevitably end with Trump’s acquittal. Florida Sen. Marco Rubio intoned that “voters themselves can hold the President accountable in an election,” while Ohio Sen. Rob Portman declaimed that the “American people will have the opportunity to have their say at the ballot box.”

Yet Alexander’s two weak arguments are directly at odds with one another. If Alexander and his fellow Republicans have chosen to abdicate their constitutional duty to pass judgment on Trump’s wrongdoing, and to hand that responsibility over to the voters, it then follows that they should have deferred to the demand of the overwhelming majority of voters to hear Bolton’s testimony, as reflected in poll after poll.

While Alexander is leaving the Senate, his Republican colleagues who will remain in the world’s greatest deliberative body will have to explain their conduct to the voters, many of them this November when they appear on the ballot together with the president in whose service they just undermined the Constitution. We will see what verdict the electorate issues.