The image of a dead man with his hands tied up behind his back on the ground in the Ukrainian town of Bucha has become a horrific symbol of Russia’s war. He was photographed bloodied, wearing jeans, sneakers and a brown hooded jacket, his hands bound by white cloth.

Days after that photo went viral, that same figure reappeared all over Moscow, where an unknown performance artist photographed himself laying on the ground, wearing similar clothes with his hands tied in front of the city’s most famous landmarks in a street art protest he called Moscow-Bucha.

Like him, hundreds of Russian artists have taken to the streets to paint anti-war graffiti in Moscow, Saint-Petersburg, Yekaterinburg, Tver, Kaliningrad, Nizhny Novgorod and other cities. Many of them are tracked down and arrested, but some get away with it. Even now, a naked mannequin covered in fake blood is lying inside a half-demolished old building in downtown Nizhny Novgorod. The word “Gruz” is written on its back, a reference to the Russian code word for soldiers killed in action. The graffiti above the mannequin reads: “Stop the War.”

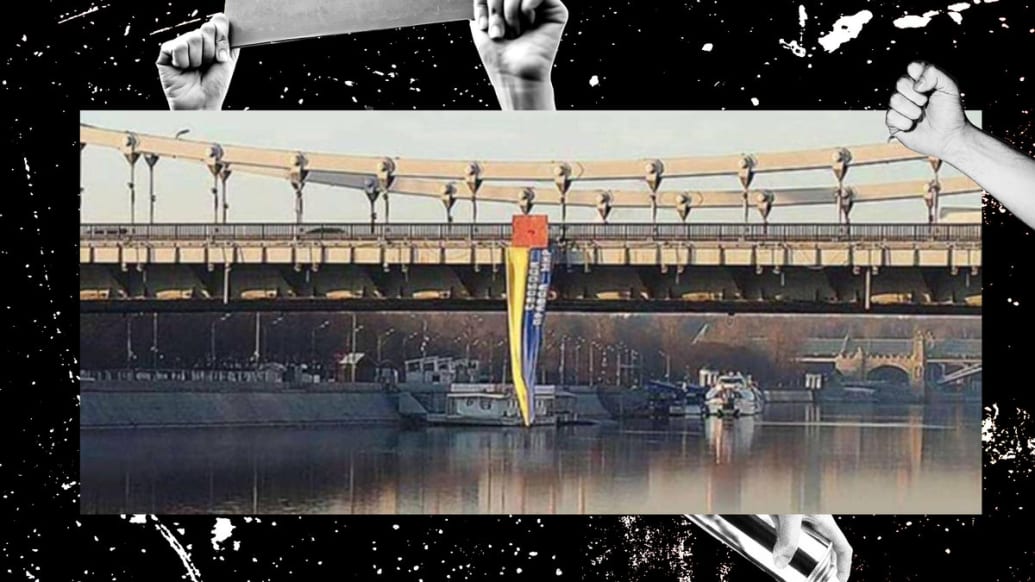

A pro-Ukrainian banner hangs off the Crimean Bridge in central Moscow. Sergei Sitar, who hung the banner, was sentenced to 15 days in prison.

Photo Illustration by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/Getty/Twitter

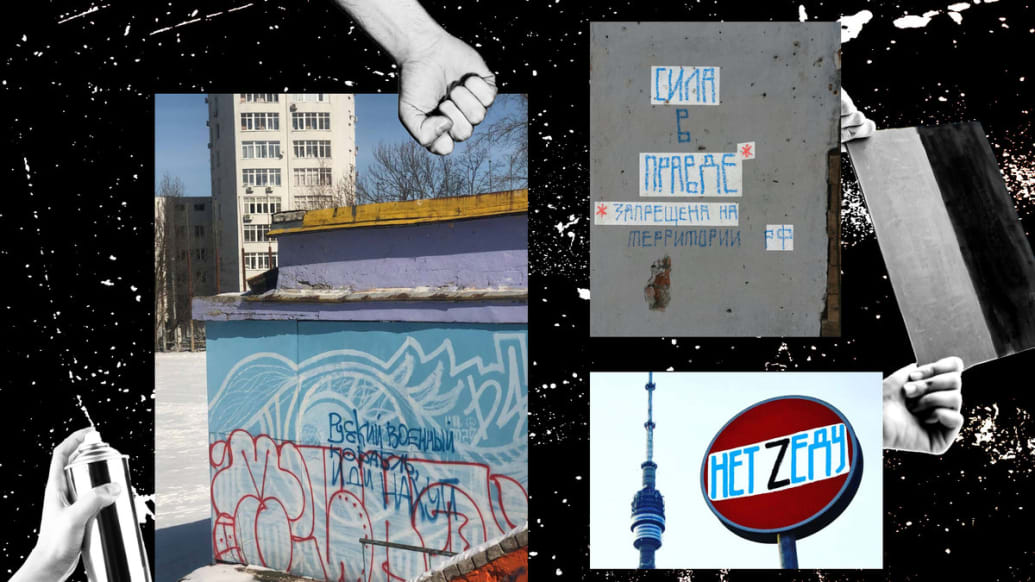

A well-known Russian architect, Sergei Sitar, hung a 10-meter Ukrainian flag painted with the words “Freedom. Truth. Peace.” on the Crimean Bridge in the center of Moscow last month. He was later sentenced to 15 days in prison over the protest by a Moscow court. Another street artist, known as the Blue Pencil, painted words on a wall in Nizhny Novgorod: “The power is in truth. It is banned on the territory of the Russian federation,” it read. Nearby, he drew a long black rectangle resembling censored text ending in an exclamation mark. “Russian authorities, because they do not change have become rotten, they turn Russia into a totalitarian state,” the Blue Pencil artist told The Daily Beast in an interview.

The tradition of political street art has deep roots in Russia. Back in 1976, the Soviet Union’s first non-conformist artist, Yuliy Rybakov, and his friends painted a 40-meter long statement on the wall of the Peter and Paul fortress in Leningrad, which read: “You crucify freedom but the human soul knows no fetters!”

Today, Russian artists stand together with Ukraine, and despite efforts to quash their protests, more anti-war art keeps appearing on the walls of Russian cities in a country where almost all opposition to the Kremlin has been silenced. Street art remains one of the only places where free expression is possible.

Tagging by Blue Pencil, a Russian street artist. In part, it reads: “Death isn’t fake.”

Photo Illustration by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/Getty/Anna Nistratova/Blue Pencil

A young Saint Petersburg artist, Zhenya Isayeva, followed Rybakov’s example earlier this month. Wearing a light white dress, she poured red paint all over herself in a protest against the bloodshed in Ukraine. “My heart is bleeding!,” she shouted, while standing on the steps of a historical building in central Nevsky Prospect until police detained her and a court sentenced her to eight days in jail.

“We see many anti-war artists and poets in Russia today because there is no free media left for expressing the horror that people feel,” Galina Artemenko, an art observer from Saint Petersburg, told The Daily Beast. “Isayeva is a serious artist from a family of artists, who have lived in Saint Petersburg for 200 years, she follows a long tradition of political art protests.”

Almost every day, Anna Nistratova, a Russian street art expert, finds new anti-war murals on the walls of Nizhny Novgorod. “Young street artists feel frustrated and angry, their statements on the walls play almost a therapeutic role for many people who disagree with what is happening,” Nistratova told The Daily Beast. “People walk along a giant wall, see a tiny ‘Stop the War’ graffiti and realize they are not alone.”

An internationally recognized Russian contemporary artist, Pavel Otdelnov, recently created a series of snow-themed paintings called A Field for Experiments. Snow is a Russian folk symbol for death. One of his paintings, called Geopolitician, depicted President Vladimir Putin’s head sticking out of a field covered in snow. “This is the image of a man who is controlling vast territories of land but he is totally lonely and half-buried in snow,” Otdelnov told The Daily Beast. “I have never felt as bad as I feel now, I cannot find a place for myself, so I try to paint so as not to fall into depression,” Otdelnov said.

Geopolitician, one of Pavel Otdelnov's snow-themed paintings featuring President Putin. “This is the image of a man who is controlling vast territories of land but he is totally lonely and half-buried in snow.”

Photo Illustration by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/Getty/Pavel Otdelnov

Other Russian artists, like the “The Party of the Dead Souls” group are turning to more direct forms of protests. Last month, they gathered in a Moscow cemetery wearing skull masks and holding banners highlighting the deaths of Russian soldiers in Ukraine. Their protest was viewed as a challenge to Russian propaganda, the lack of information about the war, and the Kremlin’s official dubious death toll when it comes to reporting Russian casualties. “This is a time for art actionism, for direct statements, like the recent performance by the Party of the Dead Souls,” Otdelnov told The Daily Beast.

At a time when citizens are arrested just for reciting classical poems with the word “war” in Russian public squares, it takes an unbelievable amount of courage for artists to take a stand against Putin’s increasingly oppressive regime.

The Party of the Dead Souls, an artist group, gather in a Moscow cemetery wearing skull masks and holding banners highlighting the deaths of Russian soldiers in Ukraine.

Photo Illustration by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/Getty/Party of Dead

“Some artists see the war as a challenge, as the time when we need to use art methods in the city environment,” the Blue Pencil told The Daily Beast. “As a street artist, I try to say that the war and murders should be stopped on the territory of Ukraine right now, I try to find [a way] to describe the horrors of the war.”