Their Husbands Were Pedophiles. So They Took Their Kids and Disappeared.

FX

Faye Yager’s underground railroad for abused children and wives is the subject of a new FX docuseries. Two women who vanished into the secret network tell their stories.

When Michelle was around 1 year old, her mother walked in on her father forcing her to fondle his penis.

“She completely came unhinged,” Michelle recalls. “She threw out all his stuff.”

With few options available—it was the 1970s—her father, Roger Jones, managed to convince her mother that he would get therapy to fix his problem. He also claimed that their doctor had prescribed her a double dose of valium (they had not). When the drugs didn’t take, Jones had her mother locked up in a mental hospital, where he signed off on the administering of 13 shock treatments over a two-week period in an effort, Michelle believes, to erase her memory.

“Pedophiles have a forked tongue,” says Michelle. “They can tell you the sky is black, and over time you start to believe it. Even though you know it’s inherently still blue, you start to think, well, maybe it might be black.”

Jones gained custody of young Michelle. The moment her mother emerged from the institution, however, she scooped up her daughter and went on the run.

“The next thing you know, I’ve got gonorrhea,” Michelle tells me. “And she thought, surely the court’s going to give my daughter over to me now because she’s tested positive, and he’s tested positive as well. But no. The court gave me back to my father.”

Over the next decade, Michelle’s mother fought in the courts to win back custody, to no avail. Meanwhile, her daughter took matters into her own hands.

“I stopped the abuse when I was 12, 13 years old. I tell this story because I want other children to know that you can stop it,” she maintains. “I felt that typical shame, but I was extremely angry. Everything had been taken from me. One day, I grabbed a .38, pointed it at him, and said, ‘I’m not gonna kill you because I want you to suffer.’”

She pauses. “You have to be stronger than they are to be able to make it.”

During her teen years, Michelle turned to drugs to help cope with her trauma, prompting her father to have her locked up in juvenile detention. Then, a miracle happened; an acquaintance informed her that they were headed down to the coast of Florida by motorcycle, so she hopped on the back and took off. She didn’t even know their last name.

While Michelle was on the run the authorities closed in on her father, who’d been accused of child sexual abuse by a number of people and became the first person on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list for child sexual assault. At 16, she returned to her mother, Faye Yager, who took the two underground. They would be the first of many.

Children of the Underground, a new five-part FX docuseries from directors Gabriela Cowperthwaite and Ted Gesing, chronicles Yager’s saga and subsequent formation of Children of the Underground, a network of off-the-grid safe houses for molested children and abused wives. The disappeared would assume new identities taken from the dead.

“It certainly wouldn’t work today with cellphones and social media,” offers Michelle. “It was a remove of clause on a second generation. So, I’m the first generation and I meet you, but I wouldn’t meet your friend, who’s the third generation, and they also have a safe house. That way, there’s deniability to where you have no idea. That’s how it worked. There was a disconnect from one to the other to the other.”

April was another mother who felt she had no other choice than to take her baby daughter, Mandy, underground.

“Mandy came home from a visit with her father and was in the bathtub and kept telling me that it hurt down there,” she tells The Daily Beast. “I pulled her out of the bathtub, and she showed me an injury, and this is pretty graphic, but it was a slit cut from her vaginal area to her anal area. I said, ‘What happened?’ And she said, ‘That’s where daddy cut me with a knife.’”

That was the first time April, who’d already split from her ex, had heard of the abuse. So, she took Mandy to the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department’s Crimes Against Children division, and they told her it was likely a crime had been committed. But because she was in the midst of a custody battle, the matter was handled in family court, where she says “the preponderance of evidence is quite different than in criminal court.”

According to April, she fought in the courts for two years, from the time Mandy was 2 to 4, trying like hell to protect her daughter.

“And there were numerous incidents. Numerous police reports. There were times where they put her in foster care, and in supervised visits with his mother where she didn’t believe anything was going on,” she remembers.

She took the two to Oregon, where Mandy was examined by a doctor who found that she had an STD.

“I got an attorney in Oregon, he sent all the documentation down to San Bernardino to arrest him, and what came back was a warrant for my arrest and a pickup order for her arrest,” April says. “That’s when I left Oregon and went up to Washington.”

It was in Washington that April crossed paths with Amy Neustein, a doctor who’d made front-page headlines when she lost custody of her daughter after an eyewitness caught her ex-husband abusing them. Neustein gave her Yager’s number, who told her she had housing and people that would help.

“A lot of the people that were hiding were survivors of sexual abuse or physical abuse, and a lot of the people [helping] were church people,” shares April. “Sometimes we would stay in people’s houses for a couple days; other times, people would pay for a hotel room for us for a week. Sometimes, it was showing up and people are throwing money and groceries at us through the car door, before I’m given another number and city to go to.”

April’s story eventually attracted media attention of its own, including “Run, Mommy, Run,” a 1988 WWOR-TV investigative report about women around the country who go on the run with their daughters, and a cover story in U.S. News & World Report. In an effort to protect the anonymity of Yager’s network, she decided to vanish from it.

“Something needs to be changed so that moms don’t have to go on the run and become criminals. It’s horrible,” says April. “I got an alias. I was a different person. You’re in social settings where you’re always on guard to make sure you’re protecting yourself. It’s like a government-witness program, only we created our own.”

Born and raised in West Virginia, Yager was the fourth of 11 children to a coal miner-father. A Southern belle with an affinity for old-fashioned dresses, she married Roger Jones at just 17, and discovered his pedophilia soon after.

In 1992, prosecutors in Marietta, Georgia, charged her with kidnapping and emotional cruelty, alleging that Yager had coerced false statements from children about their sexual abuse. She faced 60 years in prison, but was ultimately proven innocent. Six years later, a multimillionaire electronics magnate named Bipin Shah sued her in federal court for $100 million after his estranged wife took their two daughters into Children of the Underground. Time magazine placed him on their cover, and the barrage of negative media coverage led Yager to step away from the organization she’d created.

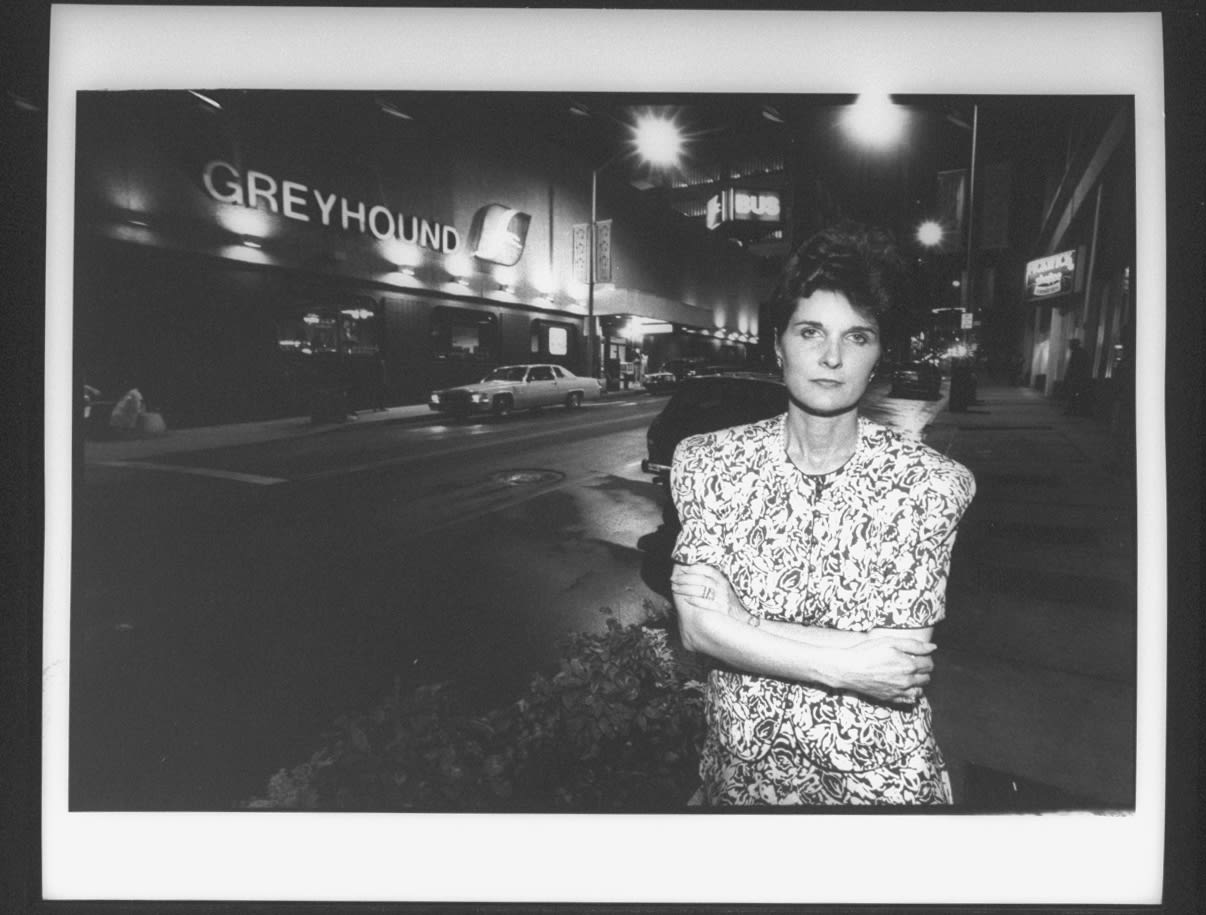

Faye Yager

Taro Yamasaki/FX

“Up until that point, she was invincible,” says her daughter Michelle. “But then she began receiving calls from people saying they were going to rape her. And my mom had to bring in the FBI at one point because she thought Bipin Shah was going to have her kidnapped. It was really ugly.”

Seven years ago, the Minneapolis Star Tribune was investigating the disappearances of Gianna and Samantha Rucki, two teenage girls who fled their homes in 2013 after accusing their father of abuse and being placed in his custody. The girls were thought to be in Children of the Underground, so the paper managed to track down Yager at her bed and breakfast in North Carolina.

“I hope they go on missing,” she said of the Rucki girls. When asked whether she knew of their whereabouts, she replied, “If I did, I wouldn’t tell you.”

According to Michelle, Yager has since ceased her involvement in Children of the Underground.

“She’s stepped away,” she says. “She has grandchildren and great-grandchildren, and she’s enjoying her life now. But the way she formed it means it can run on its own. It doesn’t need her to facilitate it. It can continue to move on.”

Experts believe that Children of the Underground has protected up to 1,000 children from their abusers, though the exact number is unknown.

“I don’t think anybody will ever know, because she’ll go to her grave with that,” says Michelle. “But she’s immensely proud of it.”