When Rayshard Brooks, a 27-year-old Black man, was shot and killed by police last summer after being woken up in the parking lot of an Atlanta Wendy’s, already raging protests over the murder of George Floyd hundreds of miles away reached new heights in the city.

Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms found herself thrust into the national spotlight, telling the Today show in June 2020 that Brooks “could have been any one of us.”

“It breaks my heart,” she said. “This went so terribly wrong.”

For a while there, it looked like the Democratic establishment in the mostly Black city might be determined to change the game. That July, the City Council went so far as to debate moving $70 million from its police budget and holding onto it to be used for policies intended to help reimagine policing.

In essence, the plan was an olive branch to the Defund the Police set. But the ordinance, dubbed by many in the community as the Rayshard Brooks Bill, failed.

Activists failing to get their way is not exactly a new tale in American municipal politics. But the blow to local community activists demanding reforms only hit harder when the city began to experience an increase in violent crime, several told The Daily Beast. In the span of the subsequent year, critics say, a once-promising conversation among local officials about reimagining policing has somehow morphed into a bizarre race to back the blue.

Now, city officials—who recently increased Atlanta’s police budget by 7 percent—are inching toward greenlighting what critics describe as a sort of new high temple to cops: an 85-acre public safety training center for police.

The facility, expected to cost $90 million and include state of the art explosive testing areas, firing ranges, and a mock city, has powerful backers. Chief among them: The Atlanta Police Foundation, an advocacy group with funding from local business and lots of political sway that has suggested the city’s “violent crime surge” underscores the “urgency” of the investment in the training center. In a June overview of the proposed project, the Police Foundation also suggested the center would increase morale and halt the exodus of officers.

But to local activists who once felt the promise of reform, the fight over the project—dubbed “Cop City” by community groups organizing in fierce opposition to it—shows how quickly national momentum toward reining in racist police violence has fallen to pieces.

Kamau Franklin, the founder of Community Movement Builders, which advocates against police brutality in the city, told The Daily Beast he never believed Atlanta would “seriously” consider defunding the police without pressure.

“But the idea of this training center is heading directly in opposition of where these conversations were going and starting to take place,” he said.

Spokespeople for the Atlanta Police Foundation and Mayor Bottoms did not respond to a request for comment for this story.

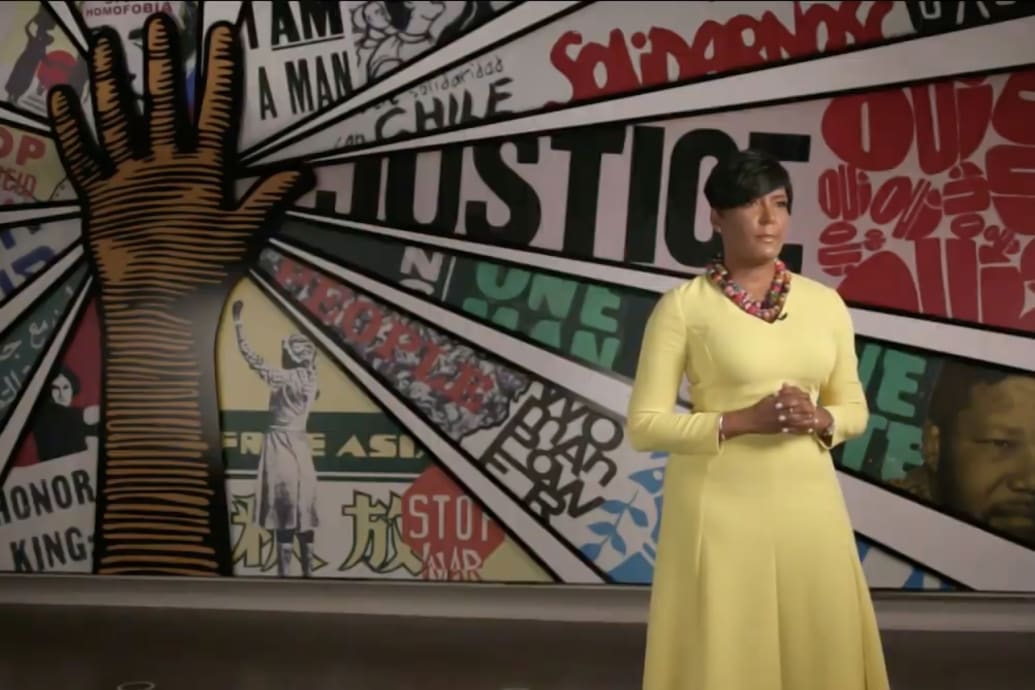

Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms addresses the virtual Democratic National Convention on August 20, 2020.

Getty

Although the training center was recently proposed to the public, Natalyn Archibong, a longtime city councilwoman, told The Daily Beast she first heard about it from the Police Foundation’s CEO Dave Wilkinson nearly four years ago. (Wilkinson did not respond to a request for comment.)

When the project was formally announced this June, it was fast-tracked with little public input, according to Archibong. Still, by the time the City Council voted on the proposal this past Monday, some opposition was beginning to crystalize, and the Council—originally expected to give it a green light—tabled the vote for a meeting in September.

Franklin, whose organization has been demonstrating against the center, called the turn of events a “small victory.”

Archibong, who made the motion to hold off on the vote, told The Daily Beast she did it because it was clear that after four hours of public input on the proposal, too few residents had been properly consulted. “To have pushed it forward,” she said, “would be patently disrespectful to the public.”

But Archibong, who voted in favor of the Rayshard Brooks Bill last year, said she, too, believes the police department needs a new training center. Her beef isn’t with the facility, but the way the Police Foundation was allowed to take the lead on selling the project, calling it a “mistake” in hindsight. Their argument—that supporting the site equated with supporting law enforcement—was “offensive and inaccurate,” she said.

Nonetheless, Archibong isn’t necessarily opposed to it, either—and said she hopes the city can take the next couple weeks to address “disinformation” that she believes has been communicated to the public about the project.

What counts as disinformation when it comes to cops in the United States in 2021 is, of course, up for some debate.

Joe Peery, an organizer with Save the Atlanta Prison Farm, said his group has been rallying to make use of the sprawling terrain where the training center would be erected. The land once served as a farm for a federal prison in the early 1900s, and later for everything from burying large zoo animals to a site for target practice for police and a place for them to safely detonate bombs.

In 2017, the city released a plan to turn the area into a public greenspace that would anchor new, future developments, Peery said. But the emerging plan for “Cop City” was an about-face from that plan, which he said had infuriated many residents, some of them concerned about the environmental effects of a training center.

“For the Atlanta Police Foundation to decide they’re going to bulldoze the center of this greenspace,” he said, “it’s just really audacious.”

Peery said he supports police having a training center in another location—unlike Franklin and other community members who oppose more funding and resources being poured into law enforcement, period. But he argued that the “hamfisted” process has effectively created a broad coalition of opponents, albeit not necessarily powerful ones.

The chief backers, besides the foundation? Rich people scared of high crime, critics say.

“It’s not fair the way this whole thing has gone down and the way they are pitting our communities against each other,” Peery said. “That’s not how you win community support. That’s how you get more and more disenfranchised with the community.”

Michael Bond, a city councilman who supports the training center, told The Daily Beast there needs to be more “community education” around the site to ease the concerns of critics like Peery. He added that although the training center was set to take up about 85 acres on the nearly 350-acre parcel of land, a big chunk of the rest of it is still planned to be left alone as preserved space, while another chunk will be developed into a public park.

He also said that concerns about the funding of the project should be allayed by the fact that the Police Foundation has committed to developing the project with its own funds, while the city leases the land to the foundation for $10 a year.

Eventually, the project, once complete, would also be turned over to the control of the city.

While Bond believes there is some convincing to be done, he said that activists like Franklin who are calling for the entire project to be scrapped—and for a move back toward defunding cops—are dreaming.

“Everybody says that sort of stuff until they have to call 911,” he said.

Do you know something we should about police or protests over police violence? Email Andrew.Boryga@thedailybeast.com or reach him securely via Signal at 978-464-1291.

Bond voted against the Rayshard Brooks Bill last year, and said he’s never regretted his vote, particularly after looking at Minneapolis, where Floyd was killed. He argued—not entirely without basis—that that city was the “genesis” of the defund the police movement, and that officials there have nonetheless scrambled to try and give more funding to police and hire more officers.

“It is really a disaster there,” Bond said.

The councilman added that if his city had gone through with their own defund proposals, they’d likely be regretting it by now.

“Atlanta would be in the very same position or worse,” Bond told The Daily Beast.

Bond conceded that the training center won’t serve to magically reduce crime once it opens up—which will take three to five years anyway. But he believes it will make a lot of progress toward recruiting and retaining higher quality officers, which he said will go a long way toward improving the situation.

“Ultimately, policing will get better,” he said. “Will it have an instantaneous effect on the crime rate? No. Probably not. But I’m sure it will help boost the morale of the people who are currently policing in the city.”

Some residents think a focus on the morale of law enforcement even as people of color say they’re being systematically targeted by cops is, well, puzzling.

The shooting death of Rayshard Brooks prompted protests and the resignation of Atlanta’s police chief.

Wes Bruer/Getty

Nolan Huber-Rhoades, an organizer with a group called Defund APD Refund Communities, said Bond’s argument is fallacy. “More policing does not keep neighborhoods safe,” he said. Instead, he argued, it will keep giving money and incentive to protect property and harm Black communities.

Cop City, he said, would only encourage the sort of “urban military tactics” that he said the city resorted to during protests last summer. “They’re going to be trained to suppress working class, multi-racial movements that challenge the status quo,” he told The Daily Beast.

Like other activists in the area, Huber-Rhoades said he was crushed when the Rayshard Brooks Bill failed last summer. “Where do we even go from here?” he remembers thinking.

But he said the training center has “reactivated” a lot of people and created a “bigger tent” of groups, including environmentalists, who are opposed to it.

Whether that means the project will be halted is an open question.

Antonio Brown, a city councilman who proposed the Rayshard Brooks Bill and has been adamant in his opposition to the training center, said he wouldn’t be surprised if it still sails through come September.

“I think that the proposal is pretty much going to remain what it is right now,” Brown told The Daily Beast.

While he’s sure more community engagement efforts will be made, he doesn’t think activists will change the minds of the majority of the council. “It’s not going to keep them from moving this training facility forward,” he told The Daily Beast.

Huber-Rhoades took a more uplifting perspective.

“We won 8 to 7 on Monday,” he said, referencing the vote to hold off on advancing the project. “At the end of last summer,” he said, alluding to the failed vote for the Rayshard Brooks Bill, “we lost 8-7.”

The change, he said, was a good sign. “But we still have more work to do.”