Walter Hill Made ‘The Warriors.’ Now He’s Back—Guns Blazing—With the Western ‘Dead for a Dollar.’

Photo Illustration by Luis G. Rendon/The Daily Beast/Getty

The filmmaker who produced “Alien” and pioneered the buddy-cop film with “48 Hours” talks to Nick Schager about his new Western and why he’s not ready to hang it up yet.

At last month’s Venice Film Festival, Walter Hill received the Cartier Glory to the Filmmaker Award for his illustrious writing and directing career. Nonetheless, 50 years since his screenplay for The Getaway propelled him on his celebrated professional path, the artist remains a maestro of modern genre storytelling, as evidenced by his newest feature, Dead for a Dollar.

A 19th-century Western about a bounty hunter (Christoph Waltz) who’s hired by a businessman (Hamish Linklater) to track down his wife (Rachel Brosnahan) and the Black army deserter (Brandon Scott) responsible for supposedly kidnapping her—a mission that eventually leads to confrontation with an old bandit nemesis (Willem Dafoe)—Hill’s film is a throwback to the classic oaters of Hollywood’s heyday, except with a particularly contemporary interest in racial and gender dynamics. It’s also, per Hill trademark, a rugged and rousing action affair of no-nonsense performances and robust set pieces, culminating with a shootout that’s as vigorous as anything in the director’s canon.

Though Dead for a Dollar is Hill’s first big-screen desperado saga since 1995’s Wild Bill, much of his cinema is indebted to the Western, from 1975’s Charles Bronson brawler Hard Times and 1987’s cartel drama Extreme Prejudice to 1996’s Akira Kurosawa remake Last Man Standing. Hill crafts moral films full of characters who adhere to (or defy, at their peril) personal codes of conduct, all while delivering a steady stream of breakneck thrills and suspense. Whether pioneering the buddy-cop genre with 1982’s 48 Hours, critiquing Vietnam with 1981’s Southern Comfort, staging a gangland epic with 1979’s The Warriors, or inspiring numerous crime works (Drive, Baby Driver, even Grand Theft Auto) with 1978’s The Driver, Hill infuses his varied projects with distinctive muscularity. That once again proves true with his latest, which reunites him with his Streets of Fire star Dafoe, and which is marked by a toughness and economy that’s rarely found in today’s domestic multiplex fare.

Hill is, quite simply, an under-sung American legend, and thus it was our great honor—ahead of Dead for Dollar’s Sept. 30 theatrical premiere—to speak with him about his fondness for Westerns, the moral foundations of his movies, and the secret to shooting great action.

Many of your films are Westerns, even if they’re not literally set in the Old West. Dead for a Dollar, however, is your first feature return to the genre since 1995’s Wild Bill. What brought you back?

Well, I did the Deadwood pilot and then I did Broken Trail [on TV]. I’m always open to making them. One of the biggest thrills I ever had as a filmmaker was, after my third film, which turned out to be something of a success, I got an offer to do a Western. I couldn’t believe it. I thought, Lord, this is heaven. It was The Long Riders. Of course, after I was signed, sealed and delivered, I got the shakes. I said to myself, Lord, this is the fortieth rendition of the Jesse James story and the James-Younger gang, and a lot of them were very good. How the hell am I going to do this in a fresh way? [Laughs] Films have their problems.

But to get to your question, I had been playing around with some ideas for a Western, none of which panned out. Then a couple years back, I was doing some reading on certain aspects of the history of the West, and I ran across a man named Chris Madsen. Chris Madsen was born in Denmark, he fought in the Danish Army against the Prussians in the war of 1864, and when that war ended a couple of years later, he joined the French Foreign Legion and did a tour of duty. Then he got on a boat, went to America, went West, joined the Army, became an Army scout. Then he left the Army and became a lawman and a bounty man. He lived a long life and had an extraordinarily honorable reputation, and I thought, this would be a good starting point for a Western, because we’re so used to the traditional Anglo figure as the bounty man, and the truth about the West is, half the people out there were immigrants.

Rachel Brosnahan, Christoph Waltz and Warren Burke in Dead for a Dollar.

Myriad Pictures

That’s fascinating.

I happened to already be friends with Christoph Waltz, so I began writing. I shaped it up and, if I may throw myself on the side of the Gods here, I wanted to use a kind of Homeric set-up where the corrupt power figure hires a professional mercenary to bring back a woman that seems like she’s abducted. Homer beat me to this idea by 2,600 years, I think. But I did tell Christoph, in instructing the writing, that he was going to be more Odysseus than Achilles. I thought that would work better. Then I just began to think, who’s a worthy antagonist? And at the same time, what are some modern issues that I can get into this? But that sounds more mechanical than it really was. A lot of it just seemed to come in the wee hours of the night, and I certainly wasn’t saying to myself, let’s be properly contemporary or something like that.

I did want to touch the traditional bases of the Western. I wanted to valorize those. I think it’s a sign of respect, beyond anything else, and also I think the audience, if it’s well-done, likes that. But I wanted to get in these contemporary issues of race and the proto-feminist movement. This is where I really had to have the overview as well as writing on automatic pilot, because I had to keep the arguments about race and about feminism contemporary within 1897. I knew that, if I turned it into a dialogue that’s totally contemporary, it would not work. It would just be a tract.

Dead for a Dollar pairs Christoph Waltz with Warren Burke, which results in a white-Black, taciturn-talkative dynamic that’s been present in a lot of your work. Is there something fundamentally American about the tension between a white and Black character, charged with figuring out how to coexist while on a joint mission? What draws you to it?

I don’t know—how’s that for an answer? We’re drawn to things that we don’t really quite understand why we are, but we find them fascinating. I think you can make a very strong case that the most consistent secondary issue in the history of America is race and race relations, and immigration, and the special place that Black people have in our country. As is often pointed out, they are the only ones who came here against their will. That’s a very salient point for trying to understand the relationships, and the nuances underpinning the relationships.

The movie, as you’ve seen, is very ensemble; it’s not just simple protagonist-antagonist. The Warren Burke character, Poe, he’s a Buffalo Soldier, and in a way, I always thought Warren had probably the hardest part to play, because he has to be one thing to the Army—“Yip yip, right sir!”, that stuff—and he’s another way with Max, Christoph Waltz’s character. He has to seem to be bending to Max’s will, but at the same time he stands up for his own position and tells Max things he doesn’t particularly want to hear. And he does it with a sense of humor and irony. Then, most critically, in dealing with his estranged friend who’s also a Black man, he has a much different kind of attitude—he’s both a good friend and a harsh critic of what Elijah’s behavior has been in the film. Warren did a great job. Listen, I was blessed with a wonderful cast, and the longer I do this, we try to be storytellers, but the way you tell the stories is through the actors. As I say, I was very fortunate with the cast that was put together.

This film, as with many of your others, is populated by characters who have moral codes, which they either stick to or resist. Do you consider yourself a moral filmmaker?

I think you have to. You do say, this is proper behavior, and this is improper behavior. I think the trick is, you have to nuance it in ways that these attitudes are complicated. Max Borlund, the Christoph character, finally has to break his own code of professionalism, and he goes over to the other side. I don’t want to spoil the drama here, but everybody finds themselves in a position where they have to pretty much renounce who they have been for what is proper action in the circumstances they now find themselves in. That goes to the local constabulary in the Mexican town; it goes to the antagonist, Joe Cribbens, played by Willem Dafoe; and it goes to the woman who ran away, Rachel Kidd, played by Rachel Brosnahan.

Dead for a Dollar, like Extreme Prejudice, ends with a grand gunfight that demonstrates your gift for shooting action. What’s the secret to giving such sequences their Hill-ian muscularity and hard-edged punch?

I think your description is possibly a little too kind, but I’m quite willing to accept it. You know, I’m a great believer that you must stay within the characters that are in the drama. In other words, they can’t suddenly get out of character in the way they conduct themselves when they’re in physical jeopardy and have to resist. So that’s the first principle, I think.

This is no longer true about so many films, which have gone a different way in the action field, but I used to always think, and I would say it to the actors and crew: the jokes are funny but the bullets are real. When we’re telling this story, that’s the truth that we’re going to live by. I usually try to get humor into the films, but the bullets are real. Now, we have lots of films where the action is really spectacular—I was going to say unbelievably spectacular, and that’s probably part of it right there [Laughs]—and those films are very popular. The audience chooses what it wants. They make the decision about what pleases them. And the action film has changed into something where the bullets are not real. The jokes may still be funny—I’m not sure, I don’t see a lot of them anymore—but nobody really seems to get killed, or even slowed down much.

You dedicate Dead for a Dollar to Budd Boetticher. Was that a nod to a particular film of his, or to the general spirit of his Westerns?

Budd and I were quite friendly toward the end of his life. We had lunch together a number of times. We weren’t best friends—I don’t want to overstate it—but he came to several of my movies, and he was a very gregarious guy and a lot of fun to be around. Of course, I was a great admirer of the Westerns that he had done with Randall Scott. But my “In Memory of Budd Boetticher” is not really about our friendship. It was that when I finished shooting the movie and got a basic cut, the first thing I said to the editor was that Budd would have liked this movie. The editor said, why? And I said, well, it’s kind of like one of his [Laughs]. It’s a small budget, most of it is out in the middle of nowhere, and it’s all about moral codes and whether or not you defy them. It’s really more of a salute to his films, I think, than even him. But of course you can’t separate the two, so I decided to do it, and I’m happy I did it.

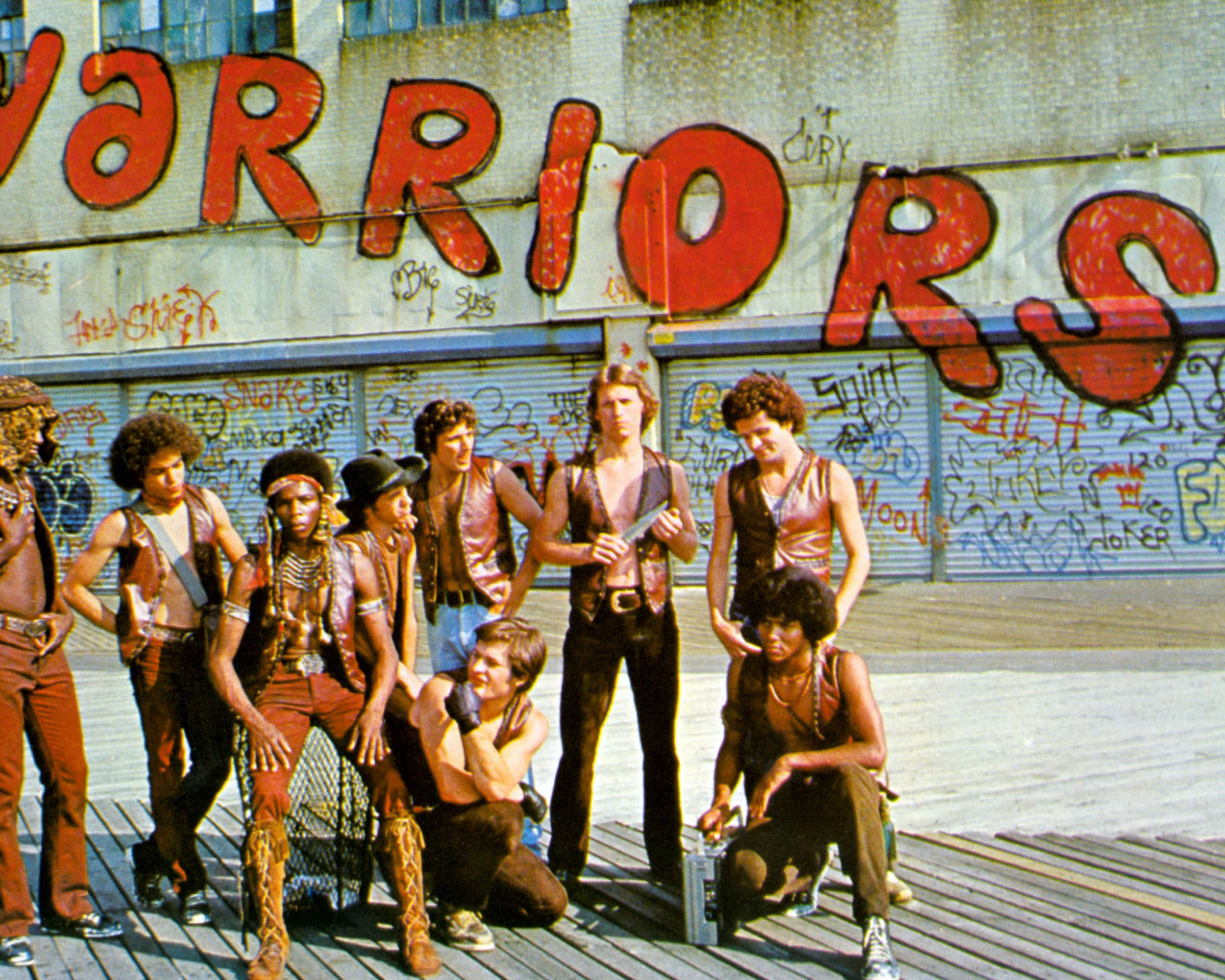

The cast of Walter Hill’s 1979 film The Warriors

Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images

After 50 years, do you hear about one of your movies more than the others?

The film that I’ve done that I get asked about more than any other by people that you run into—strangers—upon introduction, or people that come up to you, is still The Warriors. The Warriors got through to a lot of people. This last summer, I was in Italy, in Bologna, and they showed The Warriors in the Piazza Maggiore on one of those giant football screens, and they had like 8,000 people show up to watch it. I was a little apprehensive—God, this is something I did forty-plus years ago, and I wonder how the hell it holds up and I wonder how it’s going to look. It was digital, but the presentation was terrific. The film still had a nice look, and the audience was with it all the way. I don’t know what the hell to say about it. I always thought it was halfway a musical, and not as violent as its reputation somehow got to be. But I’m asked about that more than any other film.

On the flip side, are there any films of yours that you think deserve reappraisal?

That’s a hard question, and it leads to what nobody wants to hear, which is self-glorification. But I was very disappointed that Wild Bill didn’t get greater recognition for Jeff Bridges’ performance. I understood that it was a difficult film because I made it in a way that had a really fractured time structure. And the story about a man who chooses to be the legend rather than be the warm human being probably is not the most commercial idea. But I did think Jeff’s performance was staggeringly good, and I’m afraid that everything about the movie, and especially Jeff—who’s such an accomplished actor, and a lovely guy to work with—got overlooked.

Director Walter Hill speaks on stage as he is awarded with the Cartier Glory To the Filmmaker Award during the 79th Venice Film Festival on Sept. 6, 2022, in Venice, Italy.

Vittorio Zunino Celotto/Getty

You’ve worked in various genres. Is there one that you’d still like to tackle—or, at least, revisit?

There’s a certain point where you realize there’s a lot more in the rearview mirror than there is through the windshield, so I don’t know. I hope I get to do a couple more, but there aren’t a lot of directors that are operating at my age. But I’m a lucky fellow. I feel good and I seem to be in good health, knock on wood, so maybe I can go out a couple more times.

I’m trying to develop a script that Larry Gross and I have been working on called The Last Chance, which is about a saloon owner in New York in the 1970s, and it’s a drama but with lots of music attached. I’m also working on another Western. In this game, you never quite know what’s going to come together and what isn’t, so you take your chances.

You just received a lifetime achievement award at the Venice Film Festival, but here you are with a new film and with additional plans for the near future. It sounds like you have no intention of hanging it up just yet.

They always say, “Are you going to retire?” Directors, I’ve never known one who retired. You’re like a ballplayer—at some point, they come in and take your uniform away, and you go home. So far, I guess I still got my uniform.