One year ago last month, a Chinese robot touched down on the dark side of the moon.

It was the first probe to land on the side of the moon that permanently faces away from Earth as both bodies circle around the sun. And if Beijing realizes its ambitions in coming years, it won’t be the last time it makes history—and threatens U.S. dominance in space.

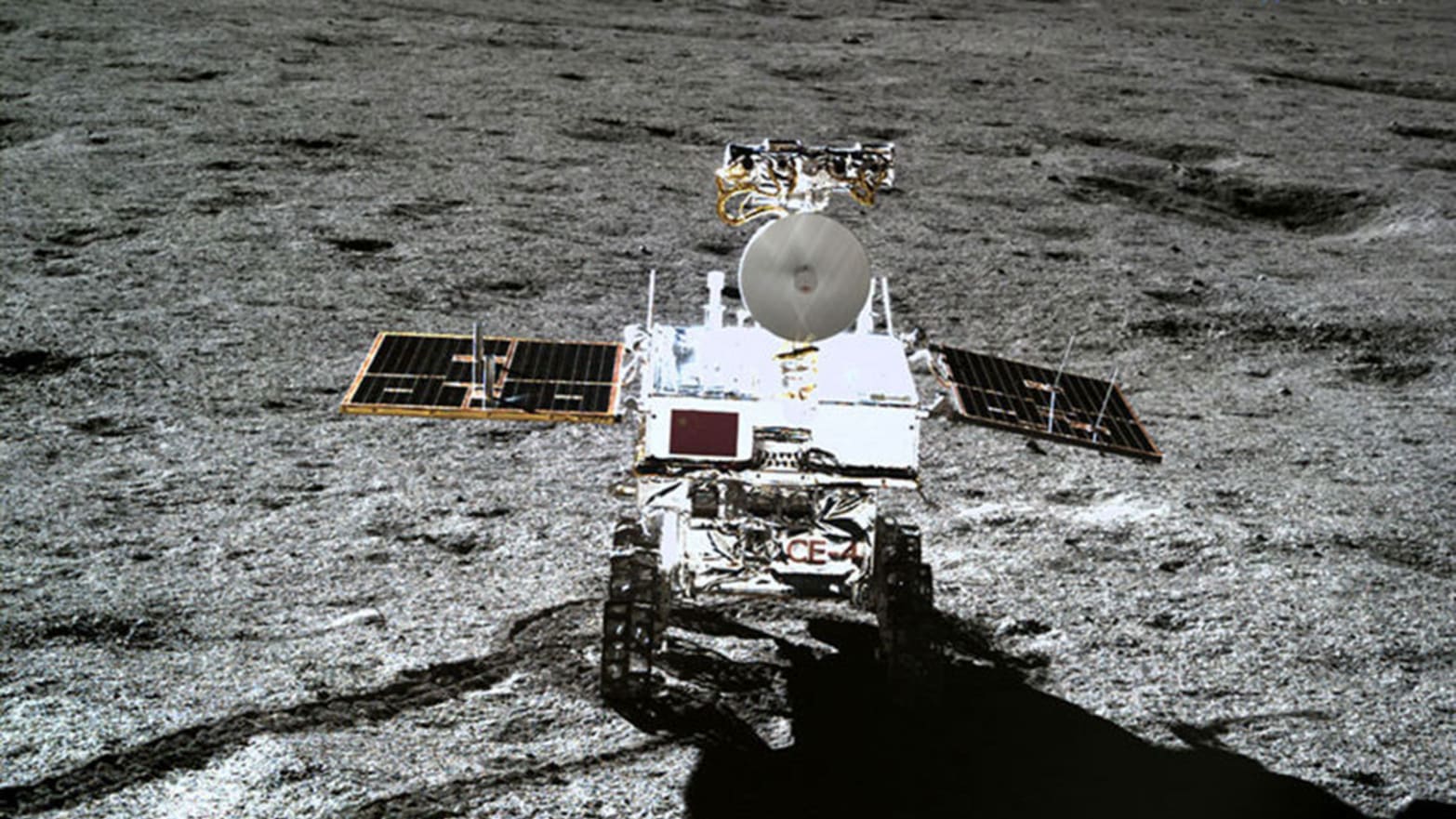

The Chang’e 4 probe and the Yutu 2 rover it carried have stayed busy photographing and scanning minerals, cultivating cotton, potato and rapeseeds, growing yeast, and hatching fruit-fly eggs in the moon’s low gravity.

The experiments are intriguing in their own right, but China’s real agenda is more than scientific. For decades, Beijing has been building the infrastructure for an eventual manned mission to the moon, effectively duplicating what the United States achieved in 1969 and hopes to achieve again before 2024.

The reasons for this latter-day space race are clear, experts said, even if the real-world pay-off isn’t.

“Space has always been symbolic of leadership, through prestige, that translates into strategic influence,” Joan Johnson-Freese, a space expert at the Naval War College in Rhode Island, told The Daily Beast. “China seeks to be acknowledged as the technology leader in Asia, and there is no more visible place to do that than space.”

While the current, high-profile U.S. moon mission is mired in Trump-era politics, China’s keeps plodding forward with fewer bold pronouncements and more actual accomplishments.

As Chang’e 4 and Yutu 2 work away, the China National Space Administration is quietly planning a follow-up probe. Chang’e 5 could blast off this year. Unlike the one-way Chang’e 4, which is limited to bouncing back data via a relay satellite, its successor is designed to collect samples and bring them back to Earth.

Meanwhile, the Chinese space agency has resumed work on its Tiangong 3 space station and is also testing a new manned capsule for deep-space missions.

When the 22-year-old, U.S.-led International Space Station finally craps out some time in the late 2020s or early 2030s, Tiangong could become the only permanent habitat in low Earth orbit. If the United States wants to maintain a significant human presence over Earth after the ISS, it might have no choice but to ask China for permission to embark.

That would make Tiangong the “de facto international space station,” Johnson-Freese argued. Neither NASA nor the Chinese space agency responded to requests for comment.

“China is in a no-lose situation,” Johnson-Freese added via email. “It can ‘beat’ the U.S. (back) to the Moon—or not—but soon thereafter be able to say anything the U.S. can do, we can do, too.”

To be clear, the United States isn’t standing still in space. NASA still leads the International Space Station and in recent years convinced Congress to keep the station in service as long as its basic components were safe and economical.

The U.S. space agency is also deploying a new space telescope and sending probes across the solar system as part of an ever-expanding search for extraterrestrial life.

And then there’s the moon. NASA for years has mulled returning human explorers to the lunar surface for the first time since 1972. Not only is there plenty of science to be done, but the moon could also function as a staging base for astronauts heading to Mars. To say nothing of the commercial value of the moon’s minerals.

Last year, the Trump administration slapped an arbitrary 2024 deadline on a new manned lunar landing. That year, of course, represents the close of a possible second term for Trump. Experts actually tend to agree 2024 is possible, but only if Congress coughs up $30 billion—and if there are zero problems developing all the hardware a moon landing requires. Tools like a new heavy rocket, a manned capsule, and a lander.

Rather than flying astronauts directly to the moon, NASA wants to build a lunar space station that could support both moon landings and future Mars missions. That complicates an American return to the moon and underscores the difference between the U.S. and Chinese approaches to space exploration.

“What China has that the U.S. has not, is long-term program-sustainability,” Johnson-Freese said. “The U.S. human exploration program has been operating in fits and starts because each new administration wants to put its stamp on whatever exploration program is announced, with a timetable, but often missing the necessary budget to make it actually feasible.”

Trump’s Moon shot has already shown signs of falling apart. Developing the manned lander was always the riskiest part, according to John Logsdon, a professor emeritus of political science and international affairs at George Washington University and a former NASA adviser. NASA hasn’t built one in nearly half a century.

Wary of throwing good money after bad, Congress approved only half of the billion dollars NASA wanted for the mission in 2020. “Our appetite doesn’t match our allocations,” Logsdon told The Daily Beast.

China’s more deliberate journey into space could be an attractive model for other, smaller space-faring countries. For decades, the United States has been the world leader in space, organizing other nations—including rivals like Russia—to explore the galaxy for the benefit of all humankind.

That could change as the competing moon missions—and the geopolitical fault lines they reflect—come into clearer focus.

“As U.S. leadership continues to erode under President Trump, other nations, especially Japan and the E.U., may begin to consider acting more independently and join China in more substantial cooperative space projects,” Gregory Kulacki, a space expert with the Massachusetts-based Union of Concerned Scientists, told The Daily Beast.

It could be decades before the end-game is clear, Christopher Impey, a University of Arizona astronomer, told The Daily Beast. “If you take the long view, which the Chinese always do, in 50 to 100 years we will be living in the solar system and there will be a substantial economic activity off-Earth,” he said.

“They want to be first,” Impey added of the Chinese, “and they want to be in the driver’s seat for that future.”