Will This Be the End of the Legendary Egyptian Museum?

DeAgostini/Getty

With its most famed objects going to a fancy new site, this most iconic of museums is approaching a crossroads, and some worry Egypt isn’t facing up to the very real challenges.

Crossing the street around Cairo’s iconic Tahrir Square is a treacherous task. The cacophony of horns suggests peril from every conceivable angle, as if eyes are required not just in the back of one’s head, but on both sides as well. Despite this being the center of the city, cars move fast, speeding toward pedestrians before executing last-minute swerves. Observing locals effortlessly sashaying their way through the carnage only adds to the intimidation as you stand on the sidewalk, nervously contemplating that first step.

The prize is clearly in sight. The majestic Egyptian Museum sends out its siren song, a neoclassical vision in salmon pink that seems at odds with the madness that envelops it. This stately old dame has been attracting visitors since 1902, all of them enticed by its collection of treasures, from the sparkly equipage of pharaohs and their chilling mummified remains to ancient stoneware and everyday items used by the masses.

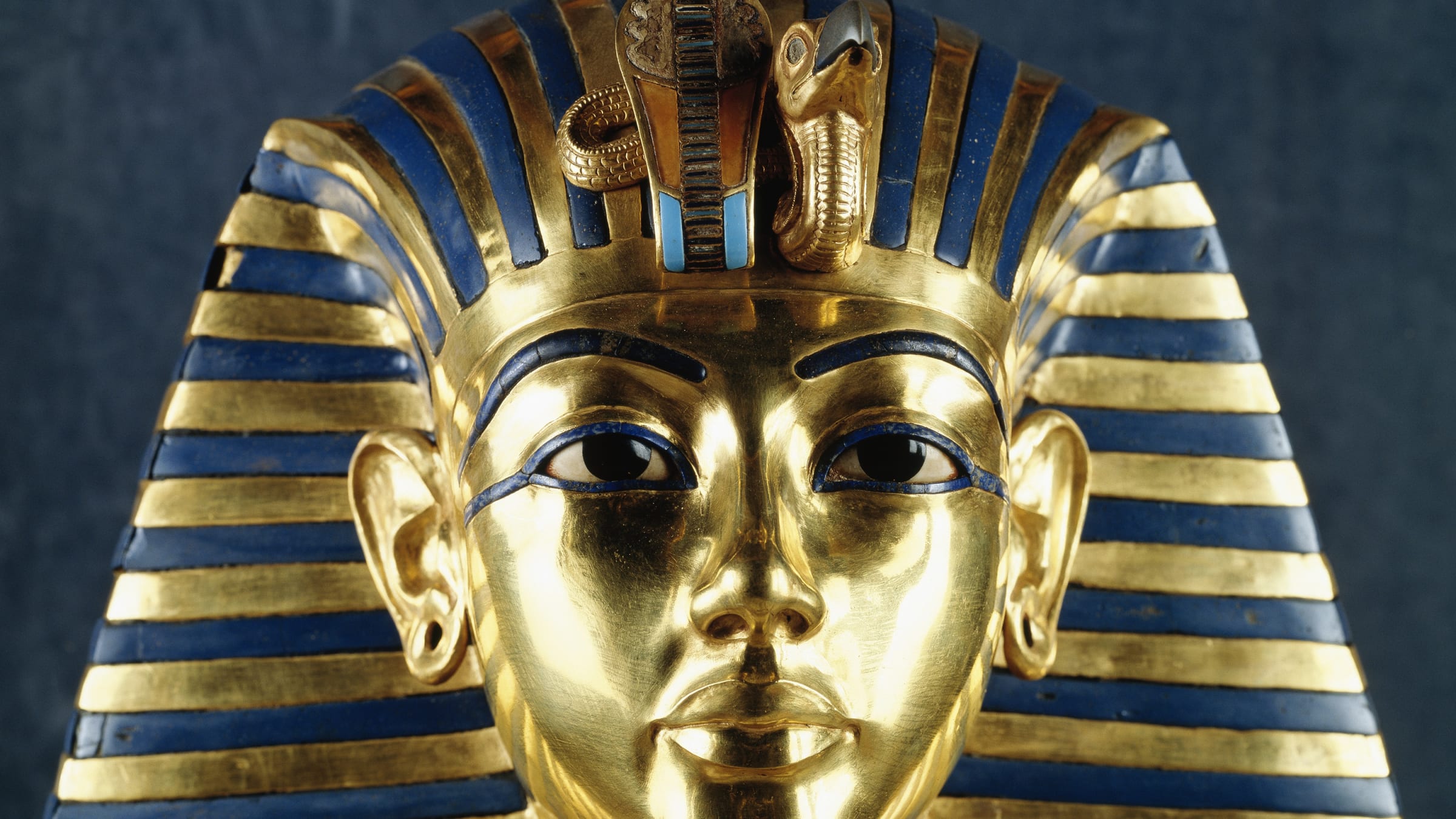

But this most iconic of museums is approaching a crossroads. Many of its items have already been shifted across town to the gigantic and modern Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM), which is slated to open next year at a cost of $1 billion and will offer visitors a state-of-the-art submersion into all things ancient Egypt. The old museum is set to lose its biggest draw, the magnificent Tutankhamun collection, to the GEM. The majority of its mummies, which many would rate as a close second, will also soon be on the move to another new competitor, the National Museum of Egyptian Civilisation, which partially opened in 2017.

The question on many a mind is whether the opening of the new GEM will see the storied Egyptian Museum revitalized or slowly descend into obscurity.

Sabah Abdel Razek, the Egyptian Museum’s director, is bullish about its future. Her office is the epitome of faded academic chic. Strip lighting saturates the room with its stark glare, a metal fan whirs agonizingly slowly overhead and pockmarked beige walls are decorated with dated gold picture frames displaying black-and-white photos of great ancient Egyptian discoveries.

"The Egyptian Museum Is Situated At Tahrir Square In Cairo, Built During The Reign Of Khedive Abbass Helmi II In 1897, Opened 1902. Among The Exhibits In Its 107 Halls Are The Tutankhamon Treasures And The Mummies."

MyLoupe/UIG Via Getty

“We will have really unique objects here, you won’t be able to find similar objects anywhere else, so that will encourage people to visit,” she says, before rattling off a list of 20 masterpieces that will remain at the Egyptian Museum. These include the Narmer Palette, a 5,000-year-old ceremonial engraving; the statue of Khafre, builder of the second pyramid at Giza; and the Tanis collection, a huge selection of glittering objects unearthed from six tombs in 1939 that some say rivals the Tutankhamun find.

The problem, according to Chris Naunton, a famed Egyptologist and author of Searching for the Lost Tombs of Egypt, is not the quantity of masterpieces but convincing visitors that the Egyptian Museum, minus its biggest draws, remains worthy of their often-limited time.

“There’s absolutely no doubt there are enough antiquities of knockout quality to fill both the GEM and the Egyptian Museum,” he says. “I think the harder question for the museum authorities to answer is: How do you avoid, whether this is fair or not, people perceiving that there’s one really good museum and one not-quite-as-good museum?”

The stick used to beat the Egyptian Museum most regularly, though, is visitor experience. In the past, it has been unfavorably compared to a store room, and there is no doubt that it charms and frustrates in equal measure. Visit during the day and dust dances in the shards of light that cascade down from the skylights in the central atrium, casting a heavenly glow upon the wonders below. Display cases are often antiques in themselves, and wandering among them transports visitors back to a time of mustachioed, pith-helmeted adventurers posing for sepia photographs with their finds before packing them up for display. Indeed, peer around certain corners and there are unopened wooden crates that look like they may well have been in situ since the turn of the 20th century, challenging you to imagine what wonders can be found inside and where they came from.

A walk through the Egyptian Museum is like walking through history itself, even before taking into account that it also houses one of the world’s most significant collections of ancient artifacts. But pervading this sense of wonder is the nagging feeling that this is a space in desperate need of some TLC.

The signage on the vast majority of artifacts is either too vague or, in many cases, non-existent. Given the sheer number of objects on display—currently about 50,000—this can result in an almost disorientating experience. Case after case of ancient marvels beg to be pored over, but with little to no information on offer, they can, tragically, end up blending into an indecipherable whole.

“The cases don’t always allow you to look at the objects properly, or at least allow you to enjoy them properly. The lighting isn’t great a lot of the time… There really is a lot to be done,” says Naunton.

Karim Shaboury, one of Egypt’s few professional museographers, agrees that the museum is primed for an update.

“It’s maybe not as practical as newer museums in terms of facilities, etc,” he says. “The space is very crowded with both objects and visitors… but it has its own style and the museum as a space is still very capable of being a great museum, especially with a program of renovation and adaptation.”

All of these issues, plus a much-needed upgrade of storage and research facilities for Egypt’s ever-growing collection of priceless antiquities, necessitated the construction of the GEM. In short, Egypt has more antiquities than it can deal with—more than most countries could deal with—and the need for huge, first-class facilities has been apparent for some time. The new museum will be located on the Giza plateau, walking distance from the pyramids and the Sphinx, thus providing an ancient Egypt one-stop-shop for visitors. This, in itself, could bring its own set of problems according to Naunton.

“The fear is that not only the Egyptian Museum on Tahrir, but almost the whole of downtown will be abandoned and forgotten about…” he says. “There are lots of things downtown that people should go and see, like the Coptic Museum, Old Cairo, the Roman Fortress of Babylon, the Mosque of Ibn Tulun—but people need to know about these things, and I think if the Egyptian tourist board presume that their very existence was enough to mean that people would go there, I think they’re kidding themselves.”

Egypt’s minister of antiquities, Khaled El-Anany, is adamant that even after the GEM’s long-awaited opening, the Egyptian Museum remains key to the country’s Egyptological offerings. “It’s an iconic museum all over the world. It’s always been the reference—and it will stay the reference,” he says.

At the turn of this year, the EU announced a project known as Transforming the Egyptian Museum of Cairo, a $3.5m collaboration between the museum, Egypt’s Ministry of Antiquities and a consortium of five European museums with expertise in museology, Egyptology, archaeology, archaeometry, and cultural heritage management.

Among them is the British Museum, and one of its curators, Ilona Regulski, will be working on the project. She says this will involve coming up with a masterplan, including a new mission statement and vision, as well as helping steer the Egyptian team towards new ways of thinking about running a museum, which has to include factors such as reaching out to visitors, marketing, press, licensing, exhibitions and loaning artifacts. She is also not shying away from the most pressing challenge: visitor experience.

“Our main strategy is display and interpretation… so that is thinking about which visitors come, what do visitors want to see, which story do you want to tell? It’s not enough to say: ‘This is a statue from the Old Kingdom.’ You have to say a bit more—who is this person, why is this person depicted like this, where does this person come from?” she says. “We’re going to write labels, banners, interpretations… I’m not at all concerned even if they take half of the objects away—there are still so many, all of which have great stories behind them that are not currently being told.”

The first phase of the project—the masterplan and redisplay of entrance galleries—is slated to take until March 2021, though the overall message seems to be evolution, not revolution. According to Abdel Razek, the museum’s director, the museum’s ground floor will host mainly artworks—an ancient art gallery of sorts—while the second floor will remain largely dedicated to collections, such as an expanded display of the incredible finds at Tanis.

In terms of attracting visitors to not one but two museums—three when including the National Museum of Egyptian Civilisation (NMEC)—El-Anany says the ministry’s plans have this covered. With Tutankhamun at the GEM, the mummies at the NMEC and “all the other iconic figures staying” at the Egyptian Museum, “tourists will be ‘obliged’ to visit all three museums to see all the masterpieces, because they will not be gathered in one museum only… GEM and NMEC will not kill the Egyptian Museum, rather they will complete each other”.

Marvelous in theory, but there is a general acceptance that the Egyptian Museum will lose some of its more casual visitors, especially those bigger tour groups that tick off the pyramids, the mummies and Tutankhamun before packing up their long lenses and heading to the souqs to engorge themselves on mass-produced miniatures of what they’ve just seen.

"An Egyptian worker cleans some of the archeological pieces inside the Egyptian Museum on February 16, 2011. Looters broke into the museum in Cairo's Tahrir Square on January 28 when anti-Mubarak protesters drove his despised police from the streets in a series of clashes, shattering 13 display cases and at least 70 artifacts, some of which have been recovered and repaired according to Hawwas. Tutankhamun's mask was not taken or damaged by looters."

Pedro Ugarte/Getty

“I think there are some things in museums that don’t need any explanation. If you put the Mona Lisa in a museum, people will go and look at it. If you put the death mask of Tutankhamun in a museum, people will go and look at it. If you put the Ashmolean Ostracon of Sinuhe in a museum, people are not necessarily going to look at it,” says Naunton. “But if you tell the story of that object: ‘This is an ancient Egyptian poem... it’s 4,000 years old and one of the earliest examples of literature from any society anywhere in the world…’ and you put an Instagram picture up saying: ‘You have to go and see this,’ all of a sudden people will go and see it.”

El-Anany, though, says that the ministry does not have specific plans to get out the message of what will be on offer in future at the Egyptian Museum. “I don’t think the Egyptian Museum needs any message, because it’s known to all tourists who have visited Egypt for decades,” he says.

Those that do stick around downtown for the Egyptian Museum, clearly should not expect sweeping changes. There has been criticism in the past of the lack of interactivity on offer—and Abdel Razek did make vague mention of touchscreens and the museum’s app—but Regulski feels that a modern museum need not necessarily embrace technology.

“I’m not such a fan of that to be honest. What we experienced in the British Museum is that it works but it requires a lot of maintenance. We have many examples where you put up a screen or something interactive and it breaks down, so here we’re actually moving back from this. I’m not excluding it, but we’re a bit hesitant,” she explains. “Often, people want to stand in front of the object and look at this marvelous thing without being distracted. And that’s especially the case for Egypt, which has the most amazing collection. Why would you fly all the way to Egypt to then look at your phone or fiddle with an app? Maybe I’m too old fashioned, but that sounds stupid, right?”

This is not to mention that excessive gadgetry might feel conspicuous in such a historic space. Much of the joy of the Egyptian Museum is mined from the fact it is more than just a showcase for its exquisite contents, this fusty old space is not only about the objects inside, it is the history of archaeology and Egyptology in physical form. There is absolute agreement from all parties that this is its key strength as the museum steps tentatively into the future.

Back in Abdel Razek’s office, with its volumes of timeworn burgundy books lining the walls and two fabulously ornate clocks rescued from Cairo’s Bulaq Museum in the 1860s, the splendor of the past looms large.

“When the museum was built it was 1902,” she says. “I’m sorry, but the GEM, of course it’s a fantastic work and it’s very big, but the Egyptian Museum has a history. And money can’t buy that.”

Any wander around the Egyptian Museum’s uncommonly charming galleries is testament to Abdel Razek’s words. The importance of its objects and of how the collection came into being is in little doubt but, for Naunton, the entire operation comes back to one key issue: engagement.

“I think Egypt does have the problem that most people have a limited appetite for ancient Egyptian stuff,” he says. “There’s no question that, even with the best will in the world, it’s going to be a challenge to put 100,000 ancient Egyptian objects in the GEM and then 50,000 objects in the Egyptian Museum and say to somebody they need to go and look at them all.”