Does Jeremy Corbyn’s victory as the new leader of the Labour Party have anything to do with our election here in the United States? Yes, it does, and Hillary Clinton and her people need to reflect on his smashing victory if she wants to win her party’s nomination and the presidency.

Economically, we may have moved on from the 2008 meltdown. Actually that’s highly debatable, or it depends on for whom. But politically, it’s practically as if it’s still 2010. People are still furious.

They’re furious, of course, about vastly different things. On the left, people are incensed about the banks and Wall Street and the 1 percent. On the right, they’re angry at the so-called moocher class and the big-spending government. But both kinds of anger go directly back to the meltdown, and the success of Bernie Sanders on the left and Donald Trump and Ben Carson on the right tell us that the two angers are very much alive.

More mainstream candidates need to wrap their heads around just what an unusual historical moment this is. E.J. Dionne put the matter really well last Friday in his little weekly joust with David Brooks on NPR. In normal economic times, he explained, conservative parties can limn the glories of capitalism and persuade people that the free-enterprise system delivers for them. Liberal parties, meanwhile, can take the wealth that system generates, or as much of it as the public will tolerate being played with, and redistribute it. This is how it works, and thus, elections are on some basic level usually about whether 51 percent of the people are feeling a little generous or a little selfish.

But post-meltdown, everything has changed. The parties of the right can’t brag about capitalism, and the parties of left have no surplus wealth to spread around. The normal conservative and liberal responses thus mooted by grim facts, people turn toward more extreme answers. Thus, Syriza in Greece, Podemos in Spain, and so on—and their counterparts, from the hard-line austerians like Angela Merkel to the revived parties of the far right like Greece's Golden Dawn and Britain's UKIP.

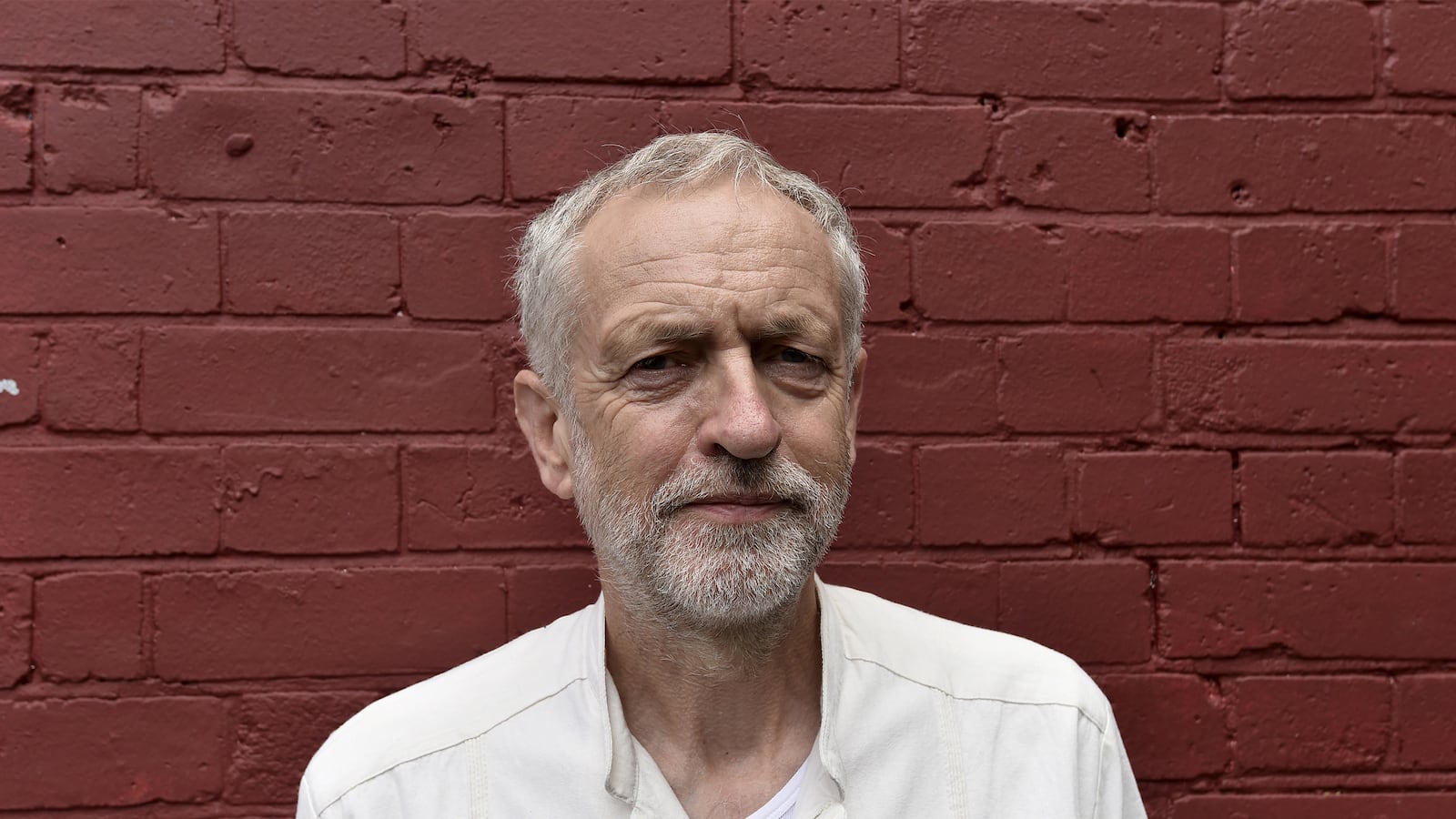

In Britain, the left-wing Corbyn demolished the competition in last week’s voting because he was the only candidate who said he’d fight against austerity. He’s a highly problematic figure in a lot of ways, especially with regard to foreign policy. But he was the only one saying what a leader of the party that supposedly represents workers ought to be saying on the fundamental economic question of our time: What is the right path back to economic health—public investments and policies that fight inequality, or their opposites?

Back now to the United States. I feel it’s a little glib and facile to say things like “Sanders is our Corbyn,” because the two men arise out of such different systems and reflect such different histories. But clearly, both are responding to and representing similar yearnings. Sanders is definitely anti-austerity, and that’s exactly what people on the broad left want to hear.

Now on to Clinton, setting aside her other problems, which I would still guess will be sorted out over time such that she’ll continue running. Clinton has embraced loads of populist positions, as I’ve written. People like me who pay attention to these things have been generally impressed. But people like me are about 2 percent of the population. What Clinton hasn’t done, at least to my hearing, is make a basic and bold and emotional pitch against austerity. She sort of does it. Her policies—public investment, paid family leave, higher capital gains tax rates—imply it. But to tap into the zeitgeist more firmly than she’s managed to so far, she has to make sure voters know that she’s in the right place on this most fundamental post-2008 question.

This doesn’t come naturally to her, to put it mildly. Her instinct to placate the establishment is strong. We saw it in her Iran speech last week. It was not, as some sniffed, a neocon speech; the neocons are anti-deal, after all. At least she’s for it. Her defense of it was as smart as any the White House has made. But then she took some more hawkish positions, with respect to future relations with Iran and as regards Russia. I don’t doubt she believes them, but there was something about the way she talked that just made it sound like she was worrying a little too much about how the speech was going to be received at the Council on Foreign Relations.

And this overabundance of prudence animates her populism, too. Compare her remarks on Greece last month to Sanders’s:

Clinton: “I think it is imperative that there be an agreement worked out with Greece. And I urge the Europeans to exert every effort to find one. Greece is a NATO ally, it is a member of the European Union. The United States has a great, active, successful Greek-American community. So I want to see a resolution.”

Sanders: “I applaud the people of Greece for saying ‘no’ to more austerity for the poor, the children, the sick and the elderly. In a world of massive wealth and income inequality, Europe must support Greece's efforts to build an economy which creates more jobs and income, not more unemployment and suffering.” He’s also, unsurprisingly, a big Corbyn cheerleader, saying over the weekend that he was “delighted” by the new pick for Labour leader.

OK, I wouldn’t expect Clinton to talk like that, but she could use a couple dashes of that vinegar. Clinton’s remarks were directed to the people who run the world; Sanders’s, to those who are run by it. Democratic primary voters are mostly the latter. Small wonder he’s connecting with them.

We’re still firmly in a post-meltdown political reality. To voters, it isn’t yet time to move on. It’s time to take sides. No one thinks Clinton should be Corbyn, since he’s almost certainly unelectable (the Scots voting nationalist in the numbers they are make it tough for any Labour candidate), but there is one big lesson she can learn from him. On the one great economic issue of the day, be loud and clear, and reassure the powerless first.