Producing great cooking can be like a permanent pursuit of the unattainable. It’s an art that is perishable and depends on performances repeated daily that require instant acclaim from those who consume it. The slightest hint of imperfection can turn a chef’s mind and, in a state of aggravated obsession, he can kill himself.

That’s apparently what just happened to Benoit Violier, proclaimed the best cook in the world by the French, his Swiss restaurant voted first of 1,000 restaurants in 48 countries. A rumor that a French food guide, Gault Millau, had lowered his ranking by a small notch and that he might lose a Michelin star had, according to French newspapers, pushed Violier over the edge.

There are several sad elements to this story, apart from the death of somebody who was without doubt at the top of his craft.

One is that anonymous French critics like those employed by Michelin continue to hold such lethal influence. The truth is that the Michelin guides represent the death throes of the self-regarding French imperium in the realm of cooking—the rest of the world isn’t listening any more.

A second is an extension of the first: For too long French arrogance has implied that nobody else in Europe knew how to scale the heights of gastronomic ecstasy to a point of madness.

I have a tragic tale to tell that proves the point.

Maleo is a dull little agricultural town in Lombardy, about an hour’s drive south of Milan. For foodies, however, there was one compelling reason to go there: the restaurant at the Albergo del Sole, run by Franco Colombani.

Franco’s place still physically resembled the old coaching inn it had once been, plain on the outside and introverted around a courtyard that in the original included stables. The rooms were plain and somewhat dank.

The main dining room was in the original kitchen, which Franco’s grandfather Giacomo took over in 1893. Giacomo’s daily kitchen diary remained on display, and was the inspiration of the Colombani family’s art. At least 20 of Giacomo’s recipes were still in use, although in the course of a century or so the kitchen’s style had moved from its rustic roots to become far more refined—refined enough to attract serious eaters from afar, including Robert De Niro, Billy Joel, and the Californian wine baron, Robert Mondavi.

And me—I heard about Franco from a friend who lived in Verona.

Franco’s menus did not go in for the serial gluttony common in neighboring Piedmont. What he looked for, he told me, was “quality and lightness.” His pasta appetisers were controlled bursts of flavor in small, simple bowls; his main dishes were often sparse arrangements of impeccably cooked meats, like the baby lamb chops my wife and I had on our first night at the Albergo: lightly grilled, dressed with garlic and parsley and served with fava beans and small white onions with a condiment of pickled red cabbage.

As fine as these dishes were, it was on our final night that Franco produced an unforgettable experience.

“I have a surprise for you,” he said, allowing himself a flicker of a smile. He had been a generous host, but until that moment a solemn one, bound up in the perfectionism of his kitchen. “The eater must value and appreciate the chef’s work,” he told us, echoing a maxim of the great epicurean A.J. Liebling that great cooking requires great eaters.

The surprise was a dish so simple and yet so considered in its coloring that it seemed a pity to violate it with a fork. The new crop of porcini mushrooms had arrived. One large mushroom head had been sautéed in oil and then crowned with the yolk of a small egg. The yolk was of an intense ochre color, the like of which I had not seen since I grew up on a farm and had pulled eggs out from under my favorite hen. The yolk was in a state delicately suspended between the solid and the liquid, its cooking timed, I suspected, to the nanosecond.

The composition was not, however, yet complete.

Franco produced a small ceramic jug and from it allowed the most delicate drizzle of balsamic vinegar. The stain of the vinegar spread like a translucent veneer over the yolk, producing an even more intense shade of ochre, like the veneer on a Stradivarius violin.

It was a perfectly composed masterpiece. One note would have been excess, one fewer just short of perfect. The vinegar’s fusion with the egg drew out the rich oiliness of the yolk and capped it with its own sour plum fruitiness, a trick of such delicacy that it was a revelation.

The next morning I asked Franco about the balsamic vinegar and discovered that it was of his own making. For that reason it did not qualify—technically—as the real stuff because it had originated there, in Maleo, not in Modena, the only certified official source for aceto balsamico tradizionale di Modena.

Franco explained what had prompted him to make his own balsamic vinegar. He had been feasting with the elders of the balsamic priesthood, the Consorteria di Aceto Balsamico Naturale of Spilamberto, a village near Modena and reckoned to be, in vinegar, the seat of the Holy Grail. The elders had all eaten at Franco’s Albergo, and invited him to dine with them to honor his kitchen’s craft.

For his part, Franco acknowledged that the aceto balsamico they had that day, in a salad of hare loin from a recipe dating from 1600, was indeed the finest. Perhaps swept away in the ecstasies of the moment, he purchased six barrels of that year’s new vinegar from Spilamberto and said he would prove, given the passage of enough years, that he could make aceto balsamico in Lombardy to equal theirs. They were graciously dismissive.

The greatest of the balsamicos all begin as a barrel of the new vinegar, which must be made by taking the unfermented musts of crushed grapes. The grapes have to be of specific varieties: the whites Trebbiano (which Franco chose), Occhio di Gatta and Spergola, the reds Lambrusco and Berzemino.

The grapes are harvested late, toward the end of October, when the musts are sweet. They are then condensed by heating and by aging. A great vinegar takes years to emerge because producing it is an extended (and expensive) reductive process, involving mysterious atmospheric influences said to be present only in the prescribed area, like the fogs that drift up from the Po River.

Franco took us across his courtyard and led us up a shaky ladder to the third floor of the old stables. Even though it was a chill autumn morning, I could detect as we climbed the signature sweet and sour aromas of the vinegar.

Franco explained that the height of the stables was a factor in the maturing of the vinegar. Lombardy’s temperature swings, from high summer heat to the damp, clinging fog-borne cold in winter, provide thermal shocks that the vinegar likes. At the top of the stables, Franco’s barrels had only a ramshackle roof between them and the sky.

There were three rows, each with the largest barrel in the middle. As it aged and became more concentrated the vinegar was transferred to progressively smaller barrels, the smallest barrels holding the final and most intense concentrate. (The sizes ranged from 100 liters to 10.)

Instead of bungs, the hole in the top of each barrel was plugged with a small cloth held in place by a stone, allowing the vinegar a controlled interaction with the air.

I lifted a stone and sniffed it, and it was strongly impregnated with aroma. I noticed that a little seepage on the floor had become like molasses that had dried to a hard, black glaze.

And so, drip by drip, the precious condiment sat there waiting for Franco’s word that it was ready to be bottled. I asked him how much a bottle would cost, if he sold it at a price that represented what it had cost him. We did a quick computation and arrived at around $500 for half a liter (and that was 20 years ago).

I gaped, he shrugged. It was an absurdity, and inconsequential to him. He had already received the ultimate compliment. He had invited the elders of Spilamberto to Maleo to taste his first batch of finished balsamico. Telling the story, he permitted himself another weak smile.

“The president of the Consorteria had to sadly note that the balsamic vinegar of Maleo was identical to that of Modena.”

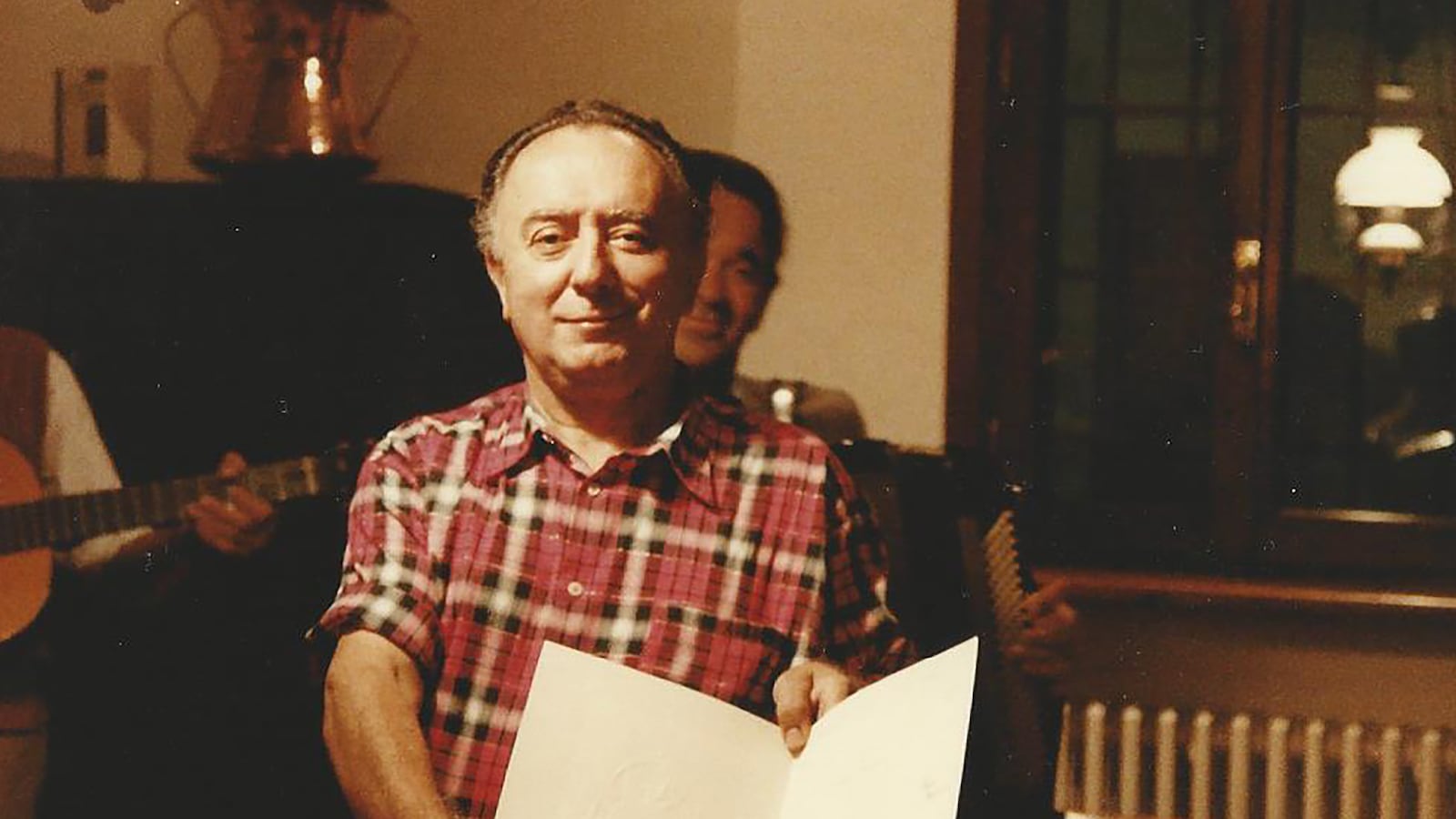

My last memory of Franco is composed like a great Dutch still life. It was on the one evening of the week that the restaurant was closed. Franco himself is missing, yet imminent. There was a single light on the big communal table that ran the length of the main dining room. Through the window we glimpsed, under the light, a table set for two.

There was a half wheel of gorgonzola so ripe that its cut face was like dripping wax veined with blue. There was a bottle and two glasses, a bowl of salad—and the little jug of balsamic vinegar. Franco and his wife were dining alone.

A year or so later I heard that Franco was dead. It had been evident while we were there that there was some deep sadness in his heart. I was told that his wife had left him, complaining that she took second place to his kitchen—and his balsamic vinegar. To be pulled between two such loves was, in the end, apparently too much. He committed suicide and the Albergo closed.