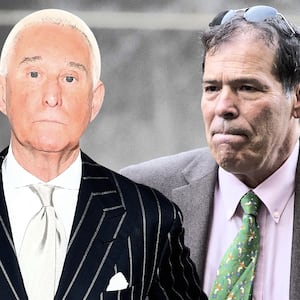

The long-anticipated indictment of Roger Stone finally dropped on Friday, and it landed on Stone like the proverbial ton of bricks. As someone who prosecuted Scooter Libby and others on similar charges and defended white-collar cases involving similar charges as those alleged here—false statements, obstruction of justice and witness tampering—my takeaway is that Stone should begin getting his affairs in order. Barring a presidential pardon (always the wild-card possibility with a POTUS like Trump) Stone will be convicted and receive a very substantial prison sentence. This is as close to a slam-dunk case as a prosecutor will ever bring.

There are several types of defenses that are typically employed when defending a case like this, and none of them are viable here.

“I didn’t actually say what the government alleges I said/the government didn’t understand what I said.”

This defense can often work when the false statements are based on an interview conducted by field agents who simply take notes of the interview and do not record it. In these instances, defendants can plausibly argue that either they did not understand the agents’ questions, or the agents either did not understand or did not memorialize their response accurately. Any ambiguity in the question or the answer can be exploited. But that won’t work for Stone, because the entire congressional hearing was transcribed, verbatim. The questions, and the answers, were under oath and were not at all ambiguous or open to interpretation.

“You can’t prove that my answer was false.”

In other words, cast doubt about the government’s version of what it alleges is the truth. Typically, this can be done by attacking the credibility of the government’s witnesses who are called to establish what the government contends actually happened. So, for example, if the government were reliant on Randy Credico or Jerome Corsi to tell the jury the “truth,” then Stone’s counsel could attack their credibility. Even the most straight-arrow witnesses can get tripped up on cross-examination on occasion. (If you doubt this, just dig up the descriptions of how Tim Russert, perhaps America’s most trusted journalist at the time, was tied up in knots on cross-examination when he testified in the Libby trial. Not pretty.)

Unfortunately for Stone, and what makes fighting this case futile, is that the government will not need to rely on the credibility of any individuals to make its case. The email and text evidence laid out in excruciating detail in the indictment is not open to interpretation. Just one example: On the very day that Stone testified that he had never sent or received emails or text messages from Credico, the two men had exchanged more than 30 text messages. Good luck spinning that.

And if that were not enough—and believe me, it is—the case will be tried in D.C. There is a facile critique that liberals are soft on crime. That can be true where the defendants are perceived to be from a disadvantaged minority. But have pity on an arrogant, white-collar defendant who is in cahoots with a despised Republican president; you will witness righteous fury. The venire in D.C. reviles Trump, and they will find Stone loathsome. The only contentiousness will be during jury selection, as the potential jurors all fight to be chosen so they can “do justice.”

Finally, do not expect to see Special Counsel Robert Mueller make any attempt to flip Stone and have him cooperate. A defendant like Stone is far more trouble than he is worth to a prosecutor. Stone is too untrustworthy for a prosecutor to ever rely upon. He has told so many documented lies, and bragged so often about his dirty tricks, that he simply has too much baggage to deal with even if here to want to cooperate—which seems unlikely in any event. Mueller, I suspect, would not even be willing to engage in a preliminary debrief with Stone to just test the possibility of cooperation out of concern that Stone would immediately go on television with his pals at Fox News to decry Mueller’s Gestapo tactics.

In short, Mueller does not need Stone to get to someone else and, even if he did, he could not rely on whatever Stone told him. Stone has nothing to sell that Mueller would be interested in buying.

Stone is clearly enjoying being in the spotlight now. He should enjoy it while he can. His remaining years won’t be nearly as pleasant.

Peter Zeidenberg is a former federal prosecutor and was a deputy special counsel in the prosecution of Scooter Libby. He is currently a white-collar partner at Arent Fox, in Washington, D.C. Follow him @przeidenberg.