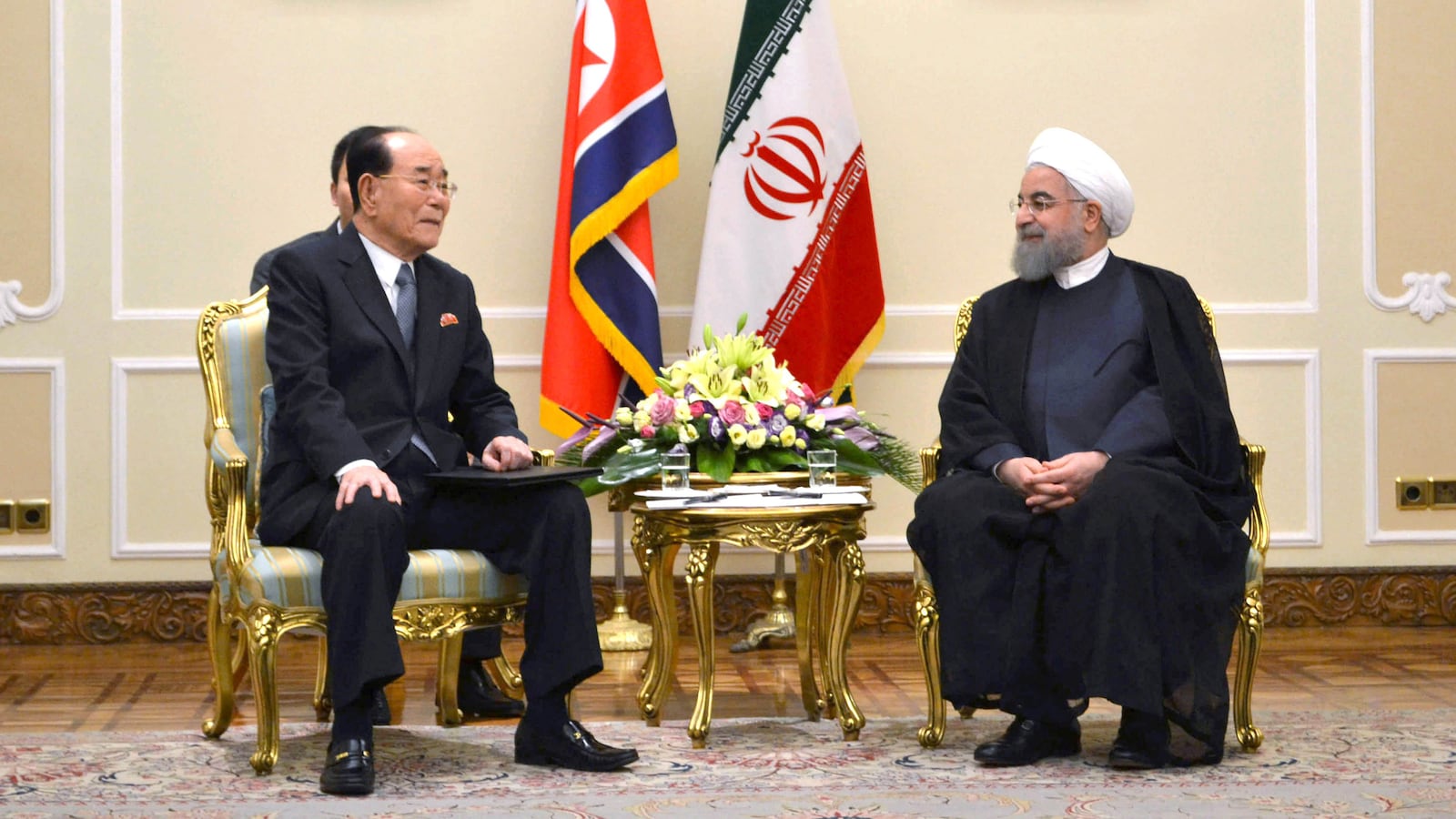

North Korea’s Kim Yong Nam was among the most mysterious, and most reported on, guests at the inauguration of Iran’s President Hassan Rouhani over the weekend. Some media, eager to boost the profile of foreign visitors to the ceremony that marked the beginning of Rouhani’s second term, cited Kim Yong Nam as the hermit kingdom’s second most powerful man.

That is slightly inaccurate, since no one is quite sure how the complex webs of power inside the North Korean regime are navigated—other than the fact that Kim Jong Un, the country’s leader and the grandson of its founder, reigns supreme. Kim Yong Nam’s most relevant title is President of the Presidium of the Supreme People’s Assembly of North Korea, which is a very long way of saying he is the speaker of the parliament.

On paper, he forms part of the executive triumvirate that includes Kim Jong Un, but his powers seem to be mostly ceremonial. Simply put, Yong Nam, who used to be the minister of foreign affairs from 1983 to 1998 under Kim Jong Un’s father, is the regime’s envoy to the world. It was he, for instance, who issued a message of congratulations to Emmanuel Macron after he was elected French president.

This isn’t Yong Nam’s first trip to Iran. He also visited in 2012 to attend the Non-Aligned Movement’s summit in Tehran. Then as now he was in the country for about 10 days, making many official visits and appearances, signing agreements for technical and educational cooperation between Iran and North Korea.

If he is forging deals to help Iran get the kind of nuclear and missile technology with which North Korea has surprised and frightened the world, but relations between the two governments go back a long way, and shared weaponry and technology has been key to their rapport.

[As The Daily Beast has reported, critics of the Iran nuclear deal with the West have gone so far as to raise the possibility that Iran continues to develop nuclear weapons and missiles inside North Korea.]

IranWire published background on the two pariah states in 2014 that helps put in perspective the curious relationship between the Islamic Republic and the world’s strangest hereditary non-monarchy.

Following are excerpts:

Iran and North Korea occupy overlapping territory in American perceptions, partly because President George W. Bush accused both countries, in his 2002 State of the Union speech, of pursuing weapons of mass destruction, mistreating their populations, and threatening world peace as members of an “axis of evil.”

Former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice has written that some people “over-interpreted” Bush’s speech to mean the axis is an alliance among the states he named (the third being Iraq), but it’s true that Iran and North Korea (which identifies itself as the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, or DPRK) have maintained an enduring relationship since 1979, based mainly on military trade and shared opposition to US interests.

A History of Shared Wounds

North Korea’s “Great Leader,” Kim Il Sung, first reached out to Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ruhollah Khomeini, in May 1979, sending him a congratulatory telegram on the “victory of the Islamic Revolution,” according to Steven Ditto, adjunct fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. On June 25th of that year, Khomeini met with DPRK Ambassador Chabeong Ouk in Qom on what Chabeong called “the 29th anniversary of the aggression of U.S. troops against the meek nation of Korea.” And Khomeini replied in kind, calling called for the expulsion of American troops from South Korea..

Bound together by anti-Americanism and a narrow foreign policy driven by resentment, Iran and the DPRK found a natural common ground from the outset. “This fit into a larger trend of Iran establishing diplomatic and trade relations with ‘non-hostile’ countries,” Ditto said. “That is, Khomeini envisioned that relations could be made with any country, regardless of ideological orientation.”

But despite both countries’ lurid expressions of hatred for the United States, the relationship was ultimately propelled by revolutionary Iran’s military needs in the early years of the Iran-Iraq War.

“The Khomeini regime was a pariah, desperate for military equipment and ammunition. They reached out to everyone they could, and few were willing to help. One of those was North Korea,” said Joseph Bermudez Jr., an analyst of the Korean People’s Army. “On the North Korean side, it’s likely that they just saw Iran as a paying customer. Iran had oil. Iran had cash. North Korea had weapons but no cash and no oil, so it was an ideal match.”

For other nations that wanted to profit from arms sales to Iran without any political cost, North Korea served as middleman. North Korea enjoyed excellent relations with the Soviet Union, and was well placed to act as a conduit for Soviet-made arms to Iran at a time when the Kremlin was wary of offending Iraq, the historian Dilip Hiro noted in The Longest War, his history of the Iran-Iraq conflict. North Korea, he wrote, also served a similar function for China, which was wary of upsetting Egypt and other Arab allies by selling Iran arms. Speedy arrival of “urgently needed” weapons from North Korea boosted the morale of Iran’s post-revolutionary forces.

A Military Relationship Forged in War

In return for Iranian financial assistance, North Korea provided Iran with the SCUD B ballistic missiles it used against Iraq in the “War of the Cities,” according to former U.S. intelligence officer Bruce Bechtol’s book Red Rogue. Even after the Iran-Iraq War ended, Iran’s military ties with North Korea deepened. Bechtol wrote that since the 1990s, North Korea has helped Iran to develop its Shahab missiles, based on North Korean models, and that “it is believed ” North Korean representatives attended Iran’s test of its Shahab-4 missile in 2006.

North Korea has had military observers in Iran since the 1980s, says analyst Bermudez, who has lectured U.S. Army and Naval intelligence staff on North Korean defense. “These people have watched U.S. operations in Iraq and the Persian Gulf, and have drawn lessons. It is likely that equipment Iran acquired from Iraq through defections or capture has been shared with North Korea.” More recently, he says, there have been persistent rumors about North Korea hosting Iranian technicians, scientists, and military officials at ballistic missile tests, and vice versa. “It’s likely,” he says, “but we can’t prove it.”

What remains unclear is whether Iran has benefited from North Korea’s longer-range missile testing. “We’d like to know whether progress being made in one country’s program is benefiting another,” said Jon Wolfsthal, deputy director of the James Martin Center for Non-Proliferation Studies. “One question that has never been adequately answered is how far does the missile cooperation go, and has it spilled over into the nuclear realm?”

Wolfsthal, who served in the White House for three years as special advisor on nuclear security to Vice President Joseph Biden, also pointed to U.S. concerns over whether the two countries share information about their nuclear programs, since North Korea has nuclear weapons. “We know that North Korea knows how to build a basic nuclear device, they’ve tested several. Is that information flowing? Iran has a very advanced centrifuge program based off the Pakistani network. We know North Korea has made some progress, but they’re not as technically skilled as some of the Iranian engineers, and so, have Iranians been helping the North Koreans perfect their uranium enrichment program?”

Diplomatic Exchanges, Friendship Farms

It is in the long history of diplomatic and cultural exchanges that the symbolic bond between Iran and North Korea can be charted. Iranian delegations traveled to the DPRK in the early 1980s and one visit included Iran’s current president, Hassan Rouhani, who traveled as a representative of Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting, meeting Kim Il Sung and counterparts from North Korea’s Radio and Television Broadcasting Committee, said Ditto.

In 1989, Iran’s current Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei visited North Korea as Iran’s president. Khamenei’s official biography quotes Ruhollah Khomeini’s son Ahmad’s claim that his father chose Khamenei as his successor based on the success of that trip.

In 1996 Iran and North Korea inaugurated “friendship farms” in each country. Every year, the farms hold cultural exchanges, commemorations of Khamenei’s visit to North Korea, and commemorations of Kim Il-Sung and Kim Jong-Il.

By the 2000s, some Iranian officials, many reformists, and “pragmatic” conservatives concerned with Iran’s integration into the global economy expressed alarm, declaring North Korea to be a negative example. In 2006, Mohsen Rezaee, Secretary of the Expediency Council and former chief of the Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), who himself led an official IRGC delegation to Pyongyang in 1993, cautioned that, should Iran follow “a reactionary stance internationally and a policy of developmental stagnation domestically,” it would fare no better than North Korea, Ditto says.

Curious details about cultural exchange emerge regularly, although rarely with much context, given the closed nature of the North Korean state.

In early 2013, the Iranian parliament approved as communications minister a former military official, Mohamed Hasan Nami, who holds a degree in “state management” from Pyongyang’s Kim Il Sung University, although there is no evidence that many Iranian officials study there.

Also in 2013, satellite images showed that Iran maintains a seven-building embassy compound in Pyongyang, at the center of which stands the first mosque in North Korea—one of only five places of religious worship in the country’s capital. In May 2009, North Korea held “Iranian Cultural Week” in Pyongyang. Details surrounding such events remain sparse.

Once Passionate, Ties Now Tepid

While both countries support each other rhetorically, by 2014 there was evidence of growing distance and diverging trajectories that may eventually cause Iran to see its friendship with North Korea as a liability.

Although there has been extensive cooperation between Iran and North Korea, and they are partners in the military realm, Alireza Nader of the Rand Corporation argued [in 2014] that they are not strictly allies. “It’s really a transactional relationship based on mutual opposition to U.S. interests, and Iran’s inability to find other military partners outside the Middle East—with the exception of, maybe, Belarus—and North Korea’s economic isolation.”

“There isn’t a common ideology there,” said Nader. “The two societies are completely different. Iran has a relatively sophisticated society, it has a sizeable middle class, it’s a merchant country [that is] susceptible to economic pressure. The government in Iran, while authoritarian, has to take public sentiment into consideration when making decisions. North Korea is a totalitarian state that lets its citizens starve.”

Diverging Trajectories

Nader suggested, however, that while North Korea is likely to maintain close links with the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps, it has little to offer the Rouhani government, which wants to improve Iran’s economy and international standing. “Rouhani,” Nader said, “is focused on improving relations with regional Arab states and European countries and potentially the United States, but also other Asian countries like China, Japan, India and South Korea. North Korea is at the bottom of that list.”

“Isolation makes strange bedfellows,” Jon Wolfsthal observes. “There’s no particular affinity between the cult of personality in North Korea and the Islamic Republic of Iran, but they have some common interests in terms of accessing hard-to-access materials, currency, luxury items [and] military equipment. Iran produces a lot of oil, North Korea needs a lot. North Korea produces a lot of ballistic missiles, Iran likes them, so they’ve been able to work out what most people believe is a pretty sophisticated barter arrangement to keep this relationship going.”

Perhaps the largest outstanding question [in 2014] was whether the two counties could maintain a relationship as Iran pursued a nuclear pact with the West. Should Iran improve its relationship with the world, association with North Korea may become an embarrassment.

“If you’re looking at the ‘brands’ of North Korea and Iran, both are pretty low in the western world, but at least Iran has something that other countries want in terms of international engagement, economic capabilities, and location,” Wolfsthal says. “So you could say that [for] Iran, being associated with North Korea, which is recognized as just a police state, could be seen as hurting their ‘brand.’”

A relationship that once thrived on friendship farms and mutually admiring founding leaders looked, in the twenty-first century, like a relic of an era that one party, at least, may hope to leave behind.

Editor’s Note: The body of this story was written before Donald Trump was elected president of the United States, and before he threatened “fire and fury” to stop North Korea’s nuclear and missile program. He may hope his rhetoric will shock and awe Iran as well. More likely, it will drive the two countries closer together once again.

—

Adapted from IranWire. The body of this article was originally written by Roland Elliott Brown in 2014. The introduction was written by Arash Azizi.