Herniated spinal discs, jaw bone fractures, broken toes, and concussions.

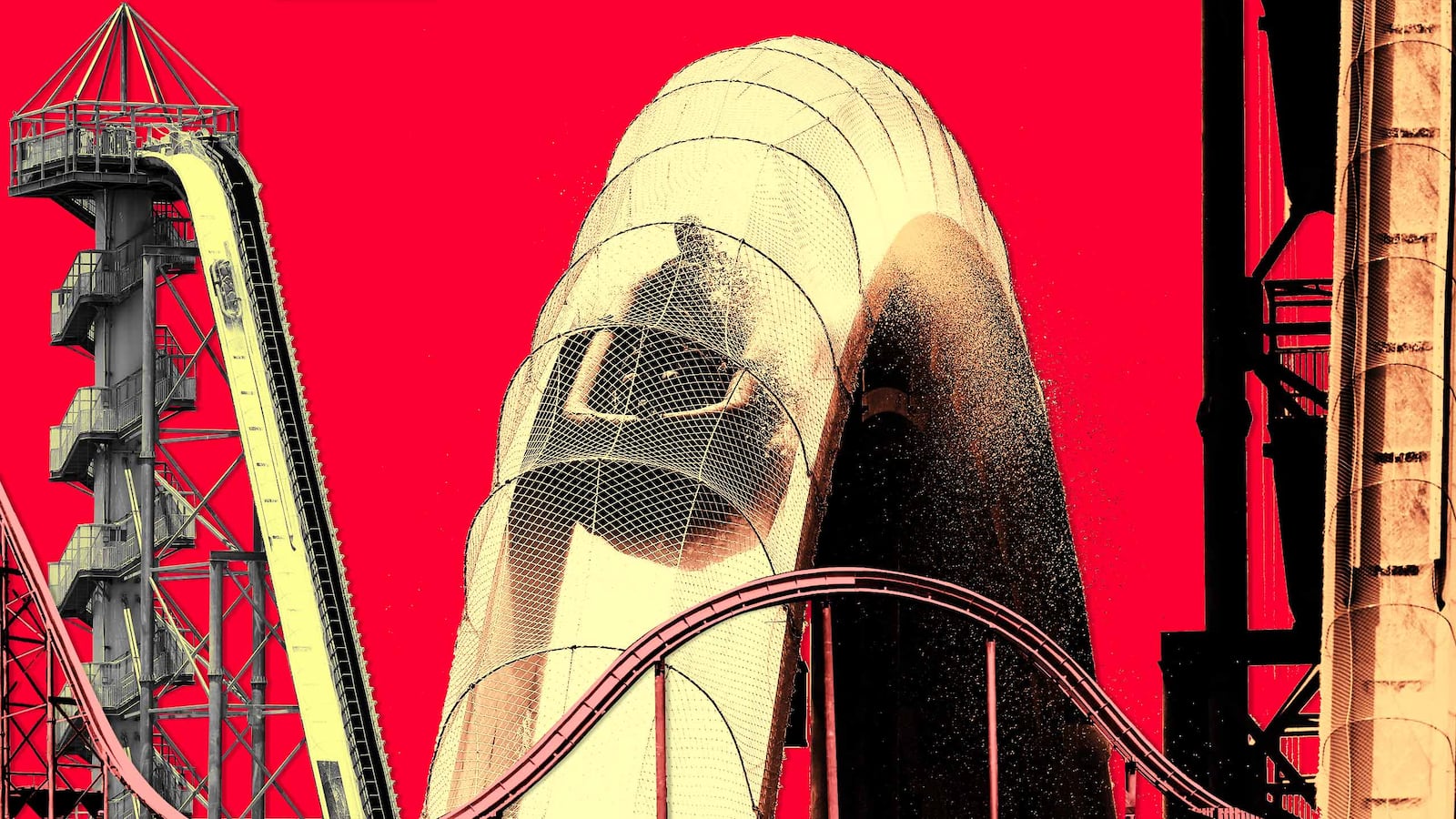

These injuries and others were suffered on the world’s tallest waterslide at Schlitterbahn Waterpark before 10-year-old Caleb Schwab was decapitated in 2016, sparking a 19-month investigation into the dangerous 17-story Verrückt attraction, according to a new indictment unsealed Tuesday.

Verrückt is German for “insane.”

The slide’s lead designer, the park’s co-owner, and a company involved in the construction were all named as defendants in 18 charges of reckless second-degree murder, aggravated battery, and aggravated endangering a child, Kansas Attorney General Derek Schmidt announced Tuesday.

Schwab, the baseball-obsessed 10-year-old son of Kansas State Rep. Scott Schwab, died when his raft went airborne and hit a metal pole attached to a safety net. Two women on his raft were seriously injured in the same accident.

A Wyandotte County grand jury indicted John Timothy Schooley, the lead designer of the 17-story Verrückt waterslide; Jeffrey Wayne Henry, a co-owner of the park and designer of the slide; and Henry & Sons Construction Co., a corporation involved in attraction’s design and building. Henry was arrested Monday in Cameron County, Texas, by U.S. Marshals, and he was held without bond pending extradition to Kansas. Schooley is not in police custody, Schmidt said in a press release.

At least 13 other people were hurt in the ride’s just 182 days of operation before Schwab’s death, including four other children, according to the indictment. Those injuries include concussions, slipped spinal discs, neck pain, whiplash, bruising, broken toes, herniated spinal discs, jaw bone fractures, orbital bone fractures, lacerations, and others.

In one case, a 15-year-old girl went temporarily blind after being on the slide, according to the indictment.

Park officials allegedly intercepted and destroyed reports of some of these injuries and told medical staff to do the same.

“Corporate emails, memoranda, blueprints, video recordings, photographs, and eyewitness statements revealed that this child’s death and the rapidly growing list of injuries were foreseeable and expected outcomes,” according to the indictment, which claims that Schooley “possesses no engineering credentials relevant to amusement ride design or safety.”

Schwab’s death “appeared at first to be an isolated and unforeseeable incident, until whistleblowers from within Schlitterbahn’s own ranks came forward and revealed” that park officials “had covered up similar incidents in the past,” another indictment, unsealed last week, alleges.

“Those responsible for Verrückt’s operation knew they were guilty of criminal misconduct, as evinced by their attempts to conceal evidence from law enforcement officers,” officials said, in the new indictment. “These obstructions substantially delayed the investigation.”

Henry, who opened the first Schlitterbahn park with his siblings in the late 1970s, turned the New Braunfels, Texas-based attraction into a popular pastime in the Lone Star State. The park later branched out to multiple locations, stretching to Florida, and Kansas City, Kansas.

The documents unsealed last week claim that Henry made a “spur of the moment” decision to build the ride, which he had no technical expertise to carry out, in order to impress producers from a Travel Channel show. What’s worse, officials claim he ignored safety warnings from consultants.

The indictments claim he rushed the project and skipped “fundamental steps in the design process.”

Schlitterbahn’s corporate parent and the company’s former director of operations, Tyler Austin Miles, were both indicted last week on a slew of related charges, including involuntary manslaughter, aggravated endangerment of a child, and aggravated battery, the Kansas City Star previously reported. (Miles has pleaded not guilty.)

The company’s spokeswoman, Winter Prosapio, previously told the Star she has “confidence that once the facts are presented it will be clear that what happened on the ride was an unforeseeable accident.”

She noted that the grand jury “never heard one word from us directly, nor were we allowed to provide contradictory evidence. And we have plenty.”