On Sunday July 19, 2015 Anthony Hervey was killed while driving home on Mississippi’s Highway 6 after attending a rally in Birmingham, Alabama to protest the city council’s decision to remove a Confederate monument in Linn Park.

A fellow passenger who survived the crash claimed that she and Hervey were being pursued by another vehicle containing four or five black men. The accident is under investigation, but given recent decisions at the state and local level to remove Confederate flags and monuments and the resulting conflicts witnessed recently, the reported cause of the crash may not come as a surprise. What may surprise readers is that Anthony Hervey was African-American.

Hervey was one of a very small but vocal group of African-American men and women who identify closely with a narrative of the Civil War that celebrates the Confederacy. These so-called “Black Confederates” have been embraced by heritage organizations such as the Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV) and United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC). In the wake of the South Carolina shootings, they have been front and center in a campaign that dates back to the late ’70s to convince the general public that thousands of free and enslaved blacks fought as soldiers in the Confederate army.

A resident of Oxford, Mississippi, Hervey was no stranger to the often contentious debates surrounding the display of the Confederate flag and other iconography. In 2000 he led protests to keep the Confederate flag flying atop the statehouse in Columbia, South Carolina and closer to home, challenged the University of Mississippi’s attempt to replace its mascot, “Colonel Reb” and ban the singing of “Dixie” during football games.

Hervey was often seen wearing a Confederate uniform and carrying a large flag in front of Oxford’s soldier statue. Among his many signs could be read: “White Guilt=Black Genocide,” “The Welfare State Has Destroyed My People,” and “Please! Do Not Hire Me Because I Am Black.” According to Hervey, it is the policies of the federal government that have fueled suspicion and deepened the racial divide in the South. In his final speech in Birmingham, just before his fatal accident, Hervey said, “I don’t like black people. I don’t like white people… but I love the hell out of me some Southerners.”

It should be no surprise that Hervey’s outspokenness in support of the Confederacy and his conservative politics endeared him to crowds at pro-Confederate heritage rallies.

Others like honorary SCV member H.K. Edgerton of North Carolina—arguably the most visible pro-Confederate African-American—also appeared at rallies throughout the South following the shootings. A one-time president of Asheville’s chapter of the NAACP, in 2002-03 Edgerton walked 1,600 miles with the flag and in full Confederate uniform from North Carolina to Texas in opposition to government policies that divide the races and in support of Confederate heritage.

At the time of his walk Edgerton asserted, “If we Southerners don’t stand together we will lose our culture, heritage, religion and region to outsiders who sadly have no appreciation of the unique culture of being Southern.”

In Virginia, Karen Cooper has maintained a close relationship with the Virginia Flaggers, which organized in 2011 to protest the removal of the Confederate flag at the “Old Soldiers’ Home” in Richmond on the grounds of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

Originally from New York and a former member of the Nation of Islam, Cooper identifies closely with her new home and with Confederate heritage. She was introduced to the Virginia Flaggers through her involvement in the tea party and quickly found a home for her views on limited government and her strong stand against a welfare state that she believes has seriously harmed the black community.

As for the history of slavery in the South, Cooper brushes it aside as having existed throughout human history and, curiously, that for every individual it was “a choice.”

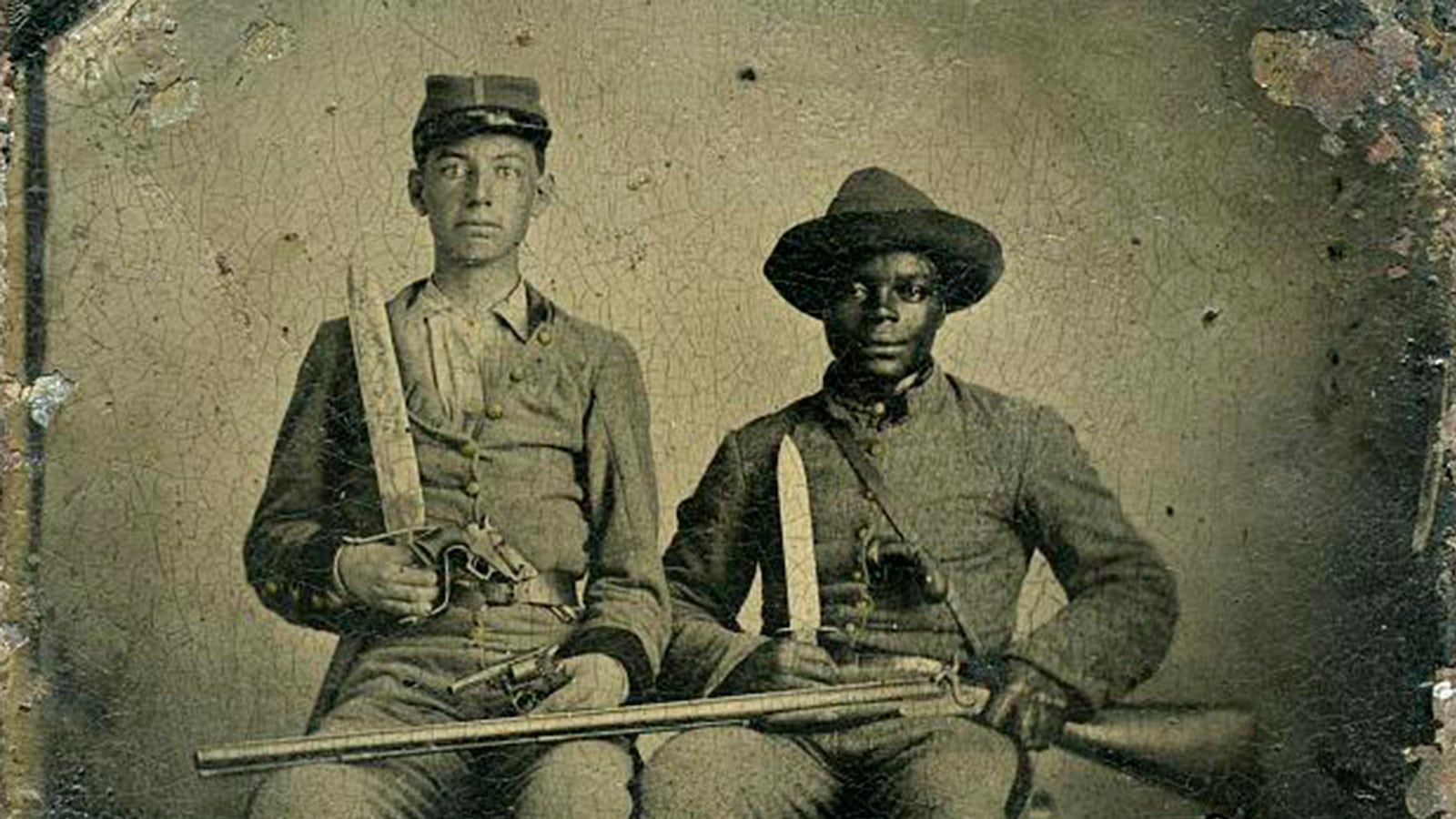

All three believe that racial unrest in the modern South and the recent divide over Confederate flags and monuments is the result of failed government policies and a false view of the history of the Confederacy. In their view, it was the Confederacy’s embrace of states rights and its own steps toward the recruitment of thousands of black Confederate soldiers that offered the promise of racial unity and equality. The willingness of all three to don Confederate uniforms and/or wave the flag offers a powerful visual reminder for those who continue to embrace a Lost Cause narrative of the Civil War—a narrative that rejects the preservation of slavery as the central goal of the Confederate experiment in independence in favor of a scenario wherein loyal black soldiers stood by their masters on the battlefield.

In their initial statement following the violent murder of nine black Charlestonians while attending Bible study at Emmanuel AME Church and the publication of photographs of Dylann Roof holding the Confederate flag, the South Carolina Division, SCV offered the following reminder:

“Historical fact shows there were Black Confederate soldiers. These brave men fought in the trenches beside their White brothers, all under the Confederate Battle Flag. This same Flag stands as a memorial to these soldiers on the grounds of the SC Statehouse today. The Sons of Confederate Veterans, a historical honor society, does not delineate which Confederate soldier we will remember or honor. We cherish and revere the memory of all Confederate veterans. None of them, Black or White, shall be forgotten.”

The SCV offered this argument not only to stem the tide of calls to lower the Confederate flag in Columbia, but to suggest that the flag has nothing at all to do with racial divisions in South Carolina. Since black men fought willingly for the Confederacy, the argument runs, the preservation of slavery and white supremacy could not have been its goal. The Confederate flag—properly understood—ought to unite black and white South Carolinians. According to the SCV, Roof’s violent act and close identification with the Confederate flag was the product of the “deranged mind of a horrendous individual.”

What few people appear to be aware of is that the black Confederate narrative is a fairly recent phenomenon. The proliferation of these stories and the zeal for the black Confederate soldier expressed by many would be alien to their Confederate ancestors, who lived under a constitution strongly devoted to protecting if not extending slavery. It was not until March 1865—after a contentious debate that took place throughout the Confederacy—that the Confederate Congress passed legislation authorizing the enlistment of slaves who were first freed by their masters. Even those who finally came to support the legislation as the only alternative to defeat would have agreed with Howell Cobb: “If slaves will make good soldiers our whole theory of slavery is wrong.” Other than a small number that briefly trained in Richmond, Virginia, no black men served openly and there is no evidence that the Richmond recruits saw the battlefield in the final weeks of the war.

Throughout the postwar period and much of the 20th century, stories of loyal black Confederate soldiers were decidedly absent. This changed in 1977 following the release and success of the popular television series Roots. At the time, the leadership within the SCV expressed concern over how the institution of slavery and race relations were portrayed in the film as well as the Confederacy itself.

SCV Commander in Chief Dean Boggs called on members to research the contributions of African Americans to the Confederate war effort to counter the series’s “propaganda.” Boggs claimed that, “Politics often ignores the truth, and the truth is that the majority of Southern Negroes, slave and free, sided [with] the Confederate effort tremendously. Some were under arms and in combat.” Both the SCV and UDC made a concerted effort to expand their membership to include African Americans by decorating the graves of former slaves who were present in the army in one of many supportive roles such as camp servants.

Broader interpretive shifts in the decades since Roots and a willingness to explore slavery, race, emancipation, and the service of United States Colored Troops at museums, historic sites, in history textbooks, at National Parks, and in popular movies such as Glory, 12 Years a Slave, and Lincoln, has magnified the importance of the black Confederate narrative for the SCV and others committed to a mythical past. The result is that it has become more and more difficult to remember the Confederacy without coming to terms with the overwhelming evidence pointing to the preservation of slavery and white supremacy as its central goal.

The Internet largely fuels confusion today about the history of slavery and the role of slaves in the Confederacy. A recent search of “Black Confederate” yielded just over a hundred thousand matches. Many of these sites are cut and pasted from one another and offer little in the way of serious analysis.

Misinformation abounds. In 2010 a Virginia history textbook, Our Virginia: Past and Present, authored by Joy Masoff, included the claim that “thousands of Southern blacks fought in Confederate ranks, including two battalions under the command of Stonewall Jackson.” When asked for the source of this claim, Masoff admitted it had been discovered online after conducting a simple search. Today it is impossible to find a reputable historian who subscribes to this history.

Confederate heritage organizations know all too well that with the increased calls to remove flags and monuments throughout the South, “Black Confederate” activists such as H.K Edgerton, Anthony Hervey, and Karen Cooper are essential to their survival. Together they will continue to fight the battles of the past and present by rallying around a mythical interracial army and encouraging one another even as an increasing number of Americans work through the tough questions that our Civil War has left us 150 years later.

Kevin M. Levin is a historian and educator based in Boston. He is the author of Remembering the Battle of the Crater: War as Murder (2012) and is currently at work on Searching For Black Confederate Soldiers: The Civil War’s Most Persistent Myth. You can find him online at Civil War Memory and Twitter @kevinlevin.