In 1941: Fighting the Shadow War: A Divided America in a World at War, historian Marc Wortman depicts how President Franklin Roosevelt led America into war long before Pearl Harbor while the nation remained deeply divided over its role in World War II. By September 1941, American “Neutrality Patrol” ships were sailing deep within Hitler’s declared Atlantic Ocean combat zone. Violent confrontation between the U.S. and Germany was inevitable. The first shots of the “undeclared war” were fired on September 4, 1941.

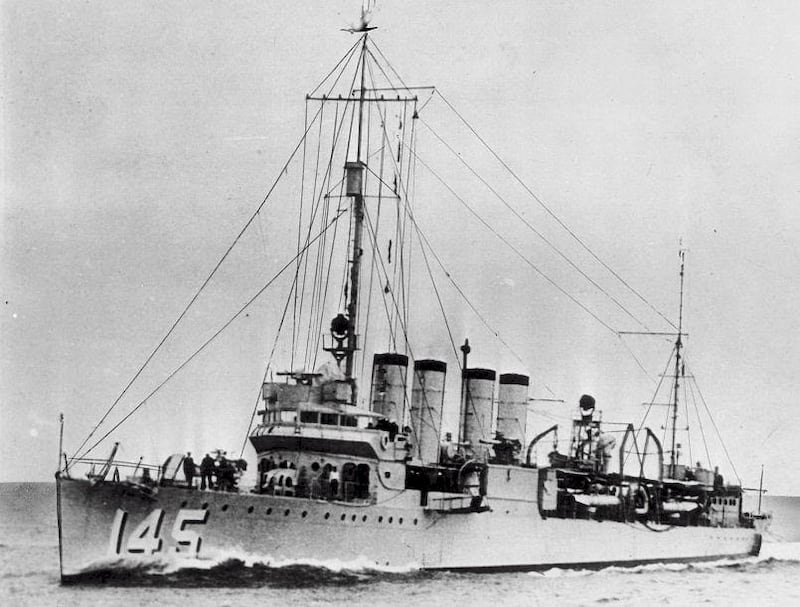

That day, deep in the North Atlantic, a naval destroyer, the USS Greer, steaming to Iceland, which American forces had occupied in early July, shadowed a German submarine. The Greer’s skipper trailed the U-boat to alert British forces. After a British patrol plane attacked the U-boat, the German commander, believing he was under attack by the destroyer, fired torpedoes in response. The Greer returned fire before breaking off the attack.

FDR knew that this “unprovoked” attack involved threatening American action. But those German torpedoes gave him the “first shot” he believed he needed to commence open hostilities. It was time to inform the American people that “undeclared” war had begun.

He waited to announce the military’s “shoot on sight” order until the evening of September 11. Perhaps deliberately, the president’s radio address to the American people and the world came in the midst of an America First rally in opposition to U.S. intervention in the war, in Des Moines. Eight thousand people were on hand to hear the anti-war forces’ most powerful spokesperson, aviation hero Charles Lindbergh. Lindbergh’s personal diaries show that, after months of hesitation and preparation, he intended to tell the American people that “other people,” Jews, British supporters, and the White House, he claimed, formed a conspiracy to push the unwilling country into war.

The Wall Street Journal calls Wortman’s new book, “...an absorbing world-wide epic ... [that] speeds ... along like a good thriller.” Here is an excerpt describing that extraordinary September 11, 1941, evening:

Charles Lindbergh stood offstage in the Des Moines Coliseum. He held the typescript of the redmeat speech he had been working on for several weeks. He was going to lay out just who was dragging America into war. Here was a chance to point fingers and put America’s true enemies, the ones pushing for war, on notice. Des Moines was no great friend to the isolationists; not only America Firsters, but a sizable contingent of their opponents as well, were among the eight thousand shouting, hooting, and whistling around the arena.

An announcer finally stepped to the podium. Instead of introducing the night’s first speaker, though, he announced that the president of the United States would address the nation first, speaking over radio from the White House. A few seconds later, Roosevelt’s familiar voice echoed out ghostly and hollow from the loudspeakers. Eight thousand pairs of ears perked up. Across the nation, throughout the Western Hemisphere, over the BBC and from there throughout Europe and the dominions of the British Commonwealth, more than a billion people gathered about radios and listened along with the Iowans to FDR’s words. ([British Prime Minister] Churchill was in bed when the broadcast went over the BBC, but heard a rebroadcast in the morning.) Billed as a “Fireside Chat,” it had little of the reassuring warmth one usually heard in the president’s voice during these talks.

A Nazi submarine, in broad daylight on the open seas, had attacked a U.S. destroyer, the USS Greer, which was doing nothing more belligerent than “carrying American mail . . . [and] flying the American flag.” His voice rose in righteous indignation: “In spite of what any American obstructionist organization may prefer to believe, I tell you the blunt fact that the German submarine fired first upon this American destroyer without warning, and with deliberate design to sink her.” Every person in the Des Moines arena knew the president was speaking to them; he, of course, knew that the true circumstances were not as he described. “This attack on the Greer,” he declared, “was no localized military operation in the North Atlantic.” Rather, he insisted, this was but “one determined step” toward world conquest.

“This Nazi attempt to seize control of the oceans,” he warned, “is but a counterpart of the Nazi plots now being carried on throughout the Western Hemisphere—all designed toward the same end. For Hitler’s advance guards—not only his avowed agents but also his dupes among us—have sought to make ready for him footholds [and] bridgeheads in the New World, to be used as soon as he has gained control of the oceans.” He was referring to the many business agents and others with Axis connections in South America, now blacklisted and in some cases jailed as a result of the Rockefeller Shop’s [Nelson Rockefeller’s Latin American intelligence and propaganda operation] and the British Security Coordination’s [the illegal British spy service based in Manhattan’s Rockefeller Center] efforts. FDR clearly also had “dupes” in Des Moines in mind.

Every eye in the crowd looked inward as the president declared, “The danger is here now—not only from a military enemy but from an enemy of all law, all liberty, all morality, all religion.” The president was not declaring war, but, he said, “when you see a rattlesnake poised to strike, you do not wait until he has struck before you crush him.” The Nazis were, he intoned, “the rattlesnakes of the Atlantic. . . .”

He had ordered his navy to “shoot on sight.” He declared, “The time for active defense has come,” and warned, “. . . if German or Italian vessels of war enter the waters . . . they do so at their own peril.” He did not make public the order he issued the day after he learned of the Greer incident: The navy would finally begin escorting convoys. As he always insisted, the U.S. had not fired the first shot, but was now free to shoot. Active combat in the undeclared war had begun.

Marc Wortman is an independent historian and award-winning freelance journalist. 1941: Fighting the Shadow War is his most recent book. He is also the author of two previous books, The Millionaires' Unit: The Aristocratic Flyboys Who Fought the Great War and Invented American Air Power (the inspiration for the prize-winning, feature-length documentary by Humanus Films) and The Bonfire: The Siege and Burning of Atlanta. He has written for many popular publications, including Smithsonian, Vanity Fair, and Town & Country, and his essays and reviews appear frequently on The Daily Beast. He and his family live in New Haven. For more information, go to: marcwortmanbooks.com.