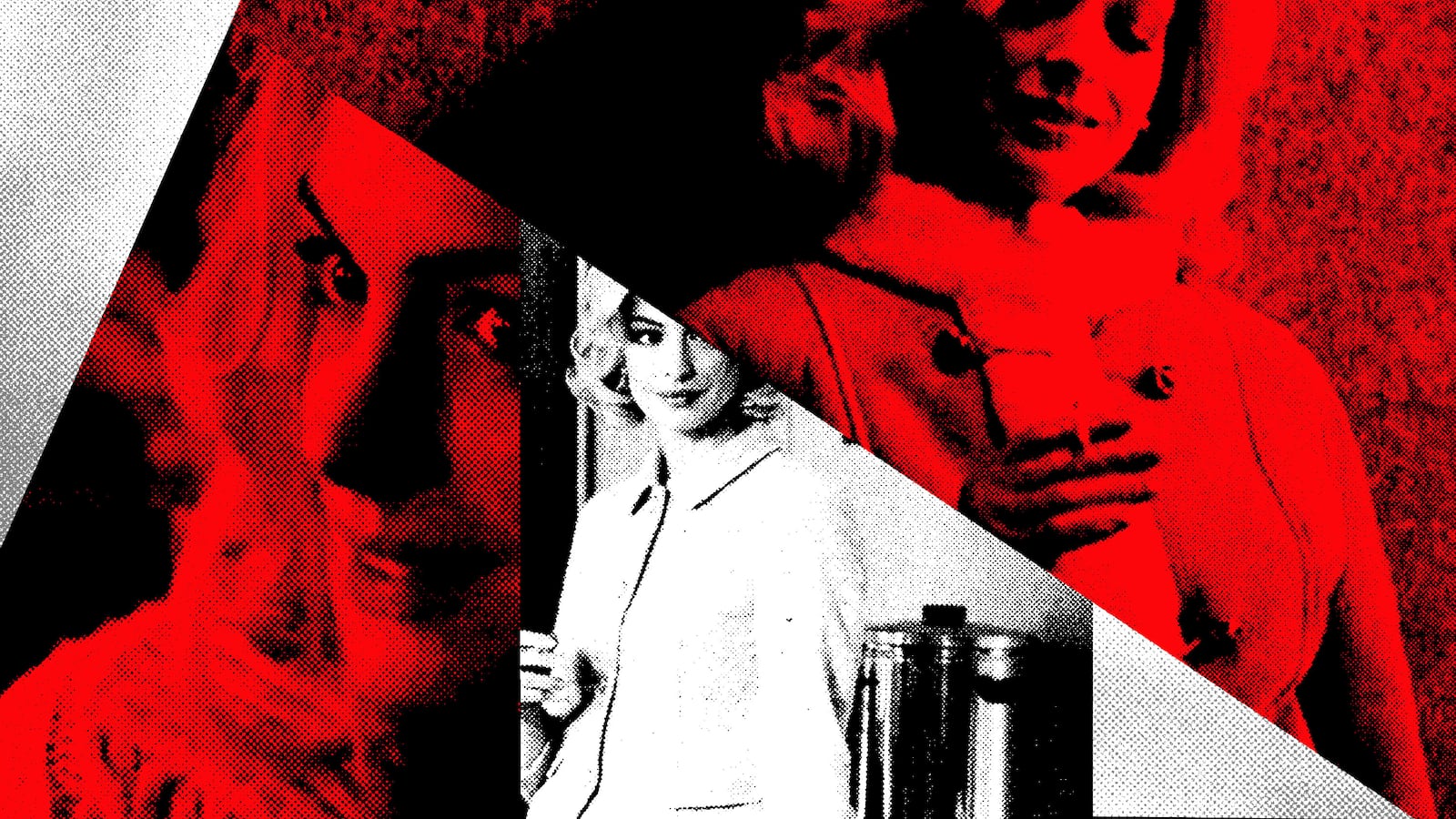

This holiday season, writer Ottessa Moshfegh cuts through the landscape of holly-jolly holiday films with a new winter thriller: Eileen.

Eileen, which takes place during a bitter, cold winter in 1964 Massachusetts, is the perfect film for anyone who wants to skip the happy-go-lucky snowy films in favor of something more frostbitten, more brooding, and more up-to-par with what the darkened days of December actually feel like. Adapted from her 2015 novel by the same name, the film is co-written by Moshfegh and her husband Luke Goebel, who also both co-wrote the 2022 Oscar-nominated film Causeway.

Moshfegh is perhaps best known for her New York Times bestseller My Year of Rest and Relaxation—which is also being adapted into an upcoming film, which has been in progress since 2018. “Still happening!” Moshfegh updates The Daily Beast’s Obsessed over Zoom. Alas, she adds, “No prediction about the timing, yet.” There’s no news on whether or not Yorgos Lanthimos, who was rumored to direct the film, is attached, either.

For now, though, fans of Moshfegh’s work have Eileen, a haunting psychological thriller with a similarly striking, complex female protagonist. Eileen Dunlop (Thomasin McKenzie) lives a dull life, spending her days working at a prison for young men and her nights arguing with her controlling father, Jim (Shea Wigham). Everything changes when Rebecca (Anne Hathaway), the glamorous new counselor for the imprisoned boys, invites Eileen into her dazzling, confusing life.

With the film expanding to wide release this weekend, Moshfegh and Goebel talk to us about the hardest part about adapting Eileen, translating a first person point of view into a screenplay, and what they think of all those comparisons to the holiday romance film Carol.

Ottessa Moshfegh and Luke Goebel at the Variety Sundance Studio in Park City, Utah.

Katie Jones/Getty ImagesEileen is the first time you’ve written an adapted screenplay together. What was the trickiest part of that?

Goebel: What was challenging was doing the book justice, at least for me. It was a book on the vanguard of a shift that happened, culturally. It was something that was so beloved by fans and made an impact. Doing the book justice, [while] working with someone that wrote it, [I was] feeling the burden of responsibility.

Moshfegh: The biggest challenge was probably getting it as short as it needed to be. We could’ve written a 10-hour movie. But we had to be selective about what scenes and what certain aspects of each character we were going to get. Making those choices, initially, was hard.

Goebel: Doing something that was both classic and really contemporary—that time that we’re with Eileen does so much in an old and a new way. To have that character, that silence and tension and even rage building, [was difficult].

It is a fairly short runtime. Was there any scene in particular that you were 100 percent certain had to make the final cut?

Moshfegh: One thing that comes to mind is the scene where Eileen wakes up in the car after getting really drunk the night before. I don’t think any of us ever questioned that scene, even though it’s kind of gross. I thought it was a gross moment that most of us could relate to.

Goebel: Seeing that carries a lot of weight. People are like, “What about the laxative scenes?” and things like that. But I think that the car vomit scene does all the work without having to go past the point of comfort for actors.

Ottessa, a lot of the women in your books are thought to be, for lack of a better word, “gross.” Do you ever feel like you have to tamp that down when you’re adapting works into feature films to make them more widely appealing?

Moshfegh: It really depends on the story and the kind of adaptation we’re doing. In the case of Eileen, I didn’t think we needed to underline certain things that the book needed to stress so much, because we could see Eileen, we could see how she moves through space, and we could see it on her face, how vulnerable and tempestuous it might be in her head. I didn’t think we needed more of her taking her feelings out on her body in any way. We kind of got it from the beginning.

Goebel: There was no impulse to tamp down anything or repress anything. When we wrote the film, the two of us with director William Oldroyd attached and [us as producers] from the start, we never had anybody telling us anything. We wanted to draw out the strong throughline, the narrative tension, and get to the key moments. The bar scene was a scene that had to be in there, things that were going to get us where we were going in terms of a narrative throughline.

The book version of Eileen is written in first person. Was it ever difficult to translate that into a more dialogue-based screenplay?

Moshfegh: For me, personally, I have a really hard time delineating: What’s the story and what’s the character? Because it’s such a character-driven story.

Goebel: Our regionality has a lot to do with it—where this is set, the time and place, the kind of forces and tension and repression. Knowing the character, that’s going to have an impact. And the timing between her and other characters, like the way in which the dialogue is set up, the force of Jim toward Eileen is going to create a natural reaction in Eileen’s face. The silences between characters, or the way in which they’re playing off each other, did a lot of informing how we imagined the actor would take the work.

The book was released in 2015; now, the movie is hitting theaters almost a decade later in late 2023. Has anything changed in the cultural climate that led you—or should lead audiences—to look at Eileen in a different light?

Moshfegh: I never thought about how the climate affected my choices, personally. But I’m sure it did somehow. Going into releasing the movie in 2023, I’m way more hopeful that conversations about the film will be broader and more interesting than the conversations around the book, which I felt kind of got stuck around an “unlikable female character.” I feel like, culturally, we’ve moved beyond that. We know that characters and books and series and films can be complicated, and women aren’t always “good.” There are deeper questions about justice and morality and trauma and parents and class psychology and prison that we can talk about.

Was that idea of the “unlikable female character” ever looming over you while you were writing the script?

Moshfegh: I was hopeful that viewers seeing Eileen would love her the way that I had always loved her. When we can externalize someone else’s vulnerability, we can have way more sympathy for it. Something about reading—where we hear our own voice in our head as we read—was particularly uncomfortable, for readers to have Eileen’s thoughts in the voice in their head rather than having externalized into another character.

Goebel: I wanted to make sure that there was never a caricature of Eileen or a one-off of Eileen. Eileen’s ability to see through the male-dominated world and to astutely critique it was all going to be done through the external acting and through the scenes and through the search for justice.

I’ve seen a lot of comparisons between Eileen and Todd Haynes’ Carol. Would you say those comparisons are valid or just convenient?

Moshfegh: I mean, I think it is convenient, but convenient not to a fault. There aren’t that many movies or stories about intimate relationships between two women that I can think of that aren’t related. We’re still at the forefront of exploring those infinite narratives with those relationships. Maybe Carol is a reference point. But I also think that it’s an interesting reference point because Eileen’s relationship with Rebecca isn’t about falling in love in a romantic or sexual way. Carol is very much on one side of that, whereas Eileen is playing this blurred line. It’s not not romantic, but it’s also not a romantic love story.