Twenty years ago, Harvey Weinstein would have turned The Taste of Things into the talk of the awards season and another Oscar night triumph for Miramax. With the disgraced mogul long gone, however, Trần Anh Hùng’s film will have to content itself with being one of last year’s standouts, as well as a must-see import when it finally receives a U.S. theatrical release this Friday, Feb. 9. Featuring a luminous Juliette Binoche and equally masterful Benoît Magimel as 1885 chefs bonded by intertwined passions, it’s a sumptuous period-piece celebration of sensory delights—both culinary and otherwise—infused with all manner of complex, intoxicating flavors.

In a private garden at dawn, Eugénie (Binoche) and others harvest vegetables and bring them into an open kitchen that’s well-stocked but far from cluttered. There, she and her young assistant Violette (Galatea Bellugi) get to work preparing a breakfast for themselves and Dodin (Magimel), a famed restaurateur and the master of the house, whom we’ll subsequently learn is affectionately known as “the Napoleon of Gastronomy” and who’s collaborated with Eugénie for the past 20 years.

At this relatively casual meal, Violette introduces Eugénie and Dodin to Pauline (Bonnie Chagneau-Ravoire), her niece, whom she’s looking after for the day. Once finished, the quartet resume their work, gutting fish, tending to veal loins, sizzling items in pans and stirring giant pots full of broth and various additional ingredients. Eugénie is at the center of this operation, executing her duties with a purposefulness that’s never hesitant or hurried, and the grace and dexterity with which she accomplishes her tasks marks her as more than merely a cook: She’s an artist.

Juliette Binoche as “Eugénie” in Tran Anh Hung’s The Taste of Things

Carole Bethuel / IFC FilmsThe Taste of Things’ first 40 minutes are spent on Eugénie and company devising a feast for Dodin and his four close confidants, who analytically and reverentially enjoy every new delicacy. Director Hùng crosscuts between these men’s faces as they sip and chew, and Eugénie and Violette as they strain, slice, add wine, and grind herbs with a mortar and pestle, creating a harmonious balance between both sides of this haute cuisine process. Cinematographer Jonathan Ricquebourg’s camera gazes intently at its subjects as they go about their undertakings, gliding from their countenances to their hands as they wrap chickens in napkins, transfer meats into and out of pans, and concoct an elaborate pastry dish that’s so striking, it’s no surprise to see Dodin and his compatriots (and also Violette and Pauline) ecstatically savor each bite.

Sensation is everything in The Taste of Things, whose primary interest is conveying that which cannot be seen. The warmth of the sun, the hissing and crackling of the stove and the fireplace, the heat of a spoonful of soup, and the moistness of expertly braised meat are so powerfully evoked that they practically overwhelm all else, and certainly take precedence over the particulars of narrative and character—at least initially. At the conclusion of this gourmet repast, everyone praises Eugénie for her “utterly exquisite” feat, wishing that she had joined them. As she makes clear, however, her place is in the kitchen, and not because of the era’s traditional gender roles (although those are omnipresent); rather, it’s because cooking is her profession, and this is where she feels most comfortable, alive, herself.

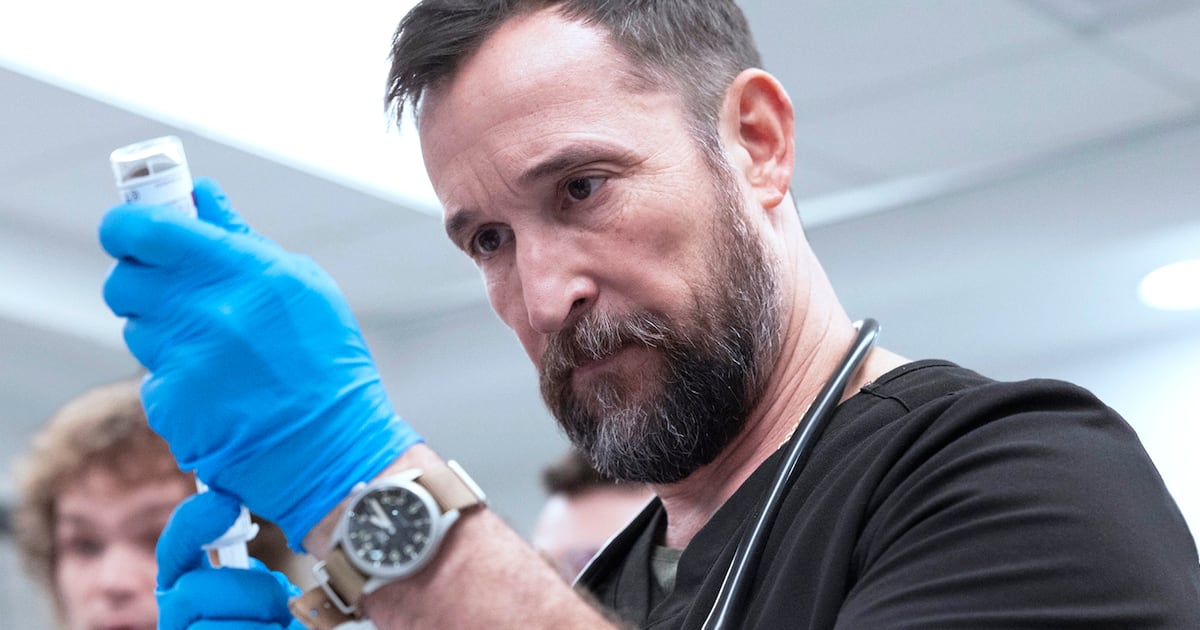

Juliette Binoche as “Eugénie” and Benoît Magimel as “Dodin” in Tran Anh Hung’s The Taste of Things

Stéphanie Branchu / IFC FilmsThe fact that, during the course of her efforts, Eugénie needs to take an unexpected breather is a warning sign about impending calamity, yet The Taste of Things is too gentle to bother with florid manipulations. Instead, its focus is on smell, taste, and touch, as well as the deeper currents that run between environment and food, food and people, the young and the old, and men and women.

Recognizing that Pauline has a gastronomical gift worth cultivating, Eugénie visits the girl’s parents and convinces them to let her serve as Dodin’s apprentice—a trip that clues Eugénie into a new method of using metal antennas to stimulate crops (with invisible electricity). At the same time, Dodin strives to convince Eugénie, his part-time lover, to accept his hand in marriage. She’s hesitant to do so, since their lives are as perfectly, precisely balanced as the meals they make together. Still, the love they feel for each other is so strong and sincere (to us, and to them) that it practically radiates off the screen, and courtesy of Dodin’s intensely romantic proposal, it ultimately can’t be denied.

The Taste of Things likes to sit with its characters, in their spaces, navigating around them with musical elegance in order to express what’s in their hearts and their heads. Reality and imagination, the tangible and the ineffable, are equally potent and exhilarating, and Hùng’s film is most magical when it intertwines the two, as when Eugénie discusses the rare occasions when she lay in bed hoping for Dodin to open her door, only to have him do so at the precise moment she thought of it. Binoche and Magimel’s chemistry is off the charts, their dynamic marked by respect, desire, history, and a shared devotion to flawlessly realizing their culinary ideas. Their post-engagement discussion about their favorite times of year speaks poignantly to the idea that each season brings with it flavors that are steeped in both the present and, just as crucially, the past.

Benoît Magimel and Juliette Binoche in Tran Anh Hung’s The Taste of Things

Carole Bethuel / IFC FilmsAfter dining with a foreign prince whose menu was excessive and clumsy, Dodin endeavors to return the favor by serving him a simpler meal consisting of pot-au-feu, arguably France’s signature dish, which Eugénie deems a plan that’s at once “hazardous and audacious.” To transform the ordinary (and “vulgar”) into something extraordinary is Dodin and Eugénie’s primary vocation, as it is with all artists, and The Taste of Things captures the alchemy inherent to their lifelong undertaking, in which knowledge, intuition and experimentation beget invention. The pleasures they create are as fleeting as their lives, but Hùng’s film understands that such ephemerality doesn’t diminish their power to arouse, to enlighten, and to provide meaning. Like love itself, they linger on long after everyone’s gone, passed onto future generations and, also, hovering in the bright summer air like an aroma so intoxicating, one can almost taste it.