Inside affords the opportunity to spend 105 minutes in the sustained company of Willem Dafoe as he slowly disintegrates under the strain of physical confinement and psychological torment—a prospect that sounds a lot better than it turns out to be. The feature debut of Greek filmmaker Vasilis Katsoupis, which hit theaters Mar. 17, is another in a long line of films in which a character is trapped in a single location (think Ryan Reynolds in a coffin in Buried, or Tom Hanks on a deserted island in Cast Away), and as a showcase for the inimitable Dafoe it has its minor freaky-deaky pleasures. Ultimately, though, it goes nowhere—literally and figuratively.

In a nocturnal New York City that glitters like a diamond and yet appears far out of reach, Nemo (Dafoe) is dropped by helicopter onto the patio of a luxury high-rise penthouse. Courtesy of an accomplice dubbed “Number Three” with whom he communicates by walkie-talkie, Nemo gains access to the residence, which is owned by a wealthy someone-or-other and whose spaces are decorated with fabulously inventive and valuable works of art (courtesy of curator Leonardo Bigazzi).

Nemo is here to steal a particular selection of those pieces, but his plans are immediately complicated by the discovery that a sought-after self-portrait is not in its expected location. Even more problematic is a high-tech security system that malfunctions when Nemo attempts to exit with his loot, thereby triggering a lockdown that confines him in the swanky locale.

With “Number Three” cutting off all communication (“You’re on your own!”) as alarms blare through the penthouse, Nemo seems to be a paddle-less man on a voyage up that famously pungent creek. Still, refusing to lose his wits, he sets about trying to disable the electro-infrastructure that rules this modernist abode, and eventually finds a way to cut off the deafening siren.

Unfortunately, the consequences of his sabotage are a busted touchscreen system that causes the heat to rise until the place is boiling at over 100 degrees. Compounding matters further, the kitchen’s smart refrigerator is almost empty, as its robo-voiced assistant routinely tells Nemo—a mocking reminder of his predicament, as is the fact that when the (barren) freezer is opened, it plays Los Del Rio’s “Macarena.”

Imprisoned by himself in a luxurious cage, Nemo strives to escape throughout the remaining course of Inside. Since he has no one with whom to communicate, most of his dialogue is relegated to the voiceover that bookends the film, during which he recalls being asked by a grade-school teacher what three items he would save from his house if it was on fire. His answers then were his cat, his AC/DC album, and his sketchbook, although he now realizes that “cats die, music fades, but art is for keeps.”

That’s an ironic idea considering his circumstances, yet director Katsoupis (working from Ben Hopkins’ script) doesn’t care much for humor. Instead, his primary focus is on the fraying psyche of his protagonist as he works to devise a means of liberation.

Initially, there’s modest puzzle-solving intrigue to Nemo’s efforts, which entail striving to cut through the home’s enormous, ornately decorated wooden front door, smash through the giant glass windows that overlook the Manhattan skyline, and construct a makeshift scaffolding furniture tower that will grant him access to a skylight.

At every turn, he’s stymied by complications and beset by extreme temperatures and injuries, forcing him to expend energy on procuring basic necessities like food and water, the last of which is obtained via sprinklers designed to nourish an outsized patch of vegetation. All the while, the penthouse’s artwork—including a video installation about an alienated couple—taunts him, as do the security-camera feeds of the building that he watches on TV as his sole form of entertainment.

Katsoupis establishes a set-up primed for race-against-time hothouse suspense, only to transform Inside into a dreamier and more languorous study of degeneration. In ways that are completely unbelievable, no one is alerted by—or shows up to investigate—this apartment’s high-tech calamity, thereby giving Nemo plenty of time to get comfortable falling apart at a leisurely pace.

Days and nights come and go in a haze as the formerly immaculate residence morphs into a disaster zone marked by ubiquitous debris and a bathtub full of its sole inhabitant’s feces. Bloody urine in the toilet suggests that Nemo may be in a bad way health-wise, but the proceedings’ unreality is such that those concerns never amount to anything.

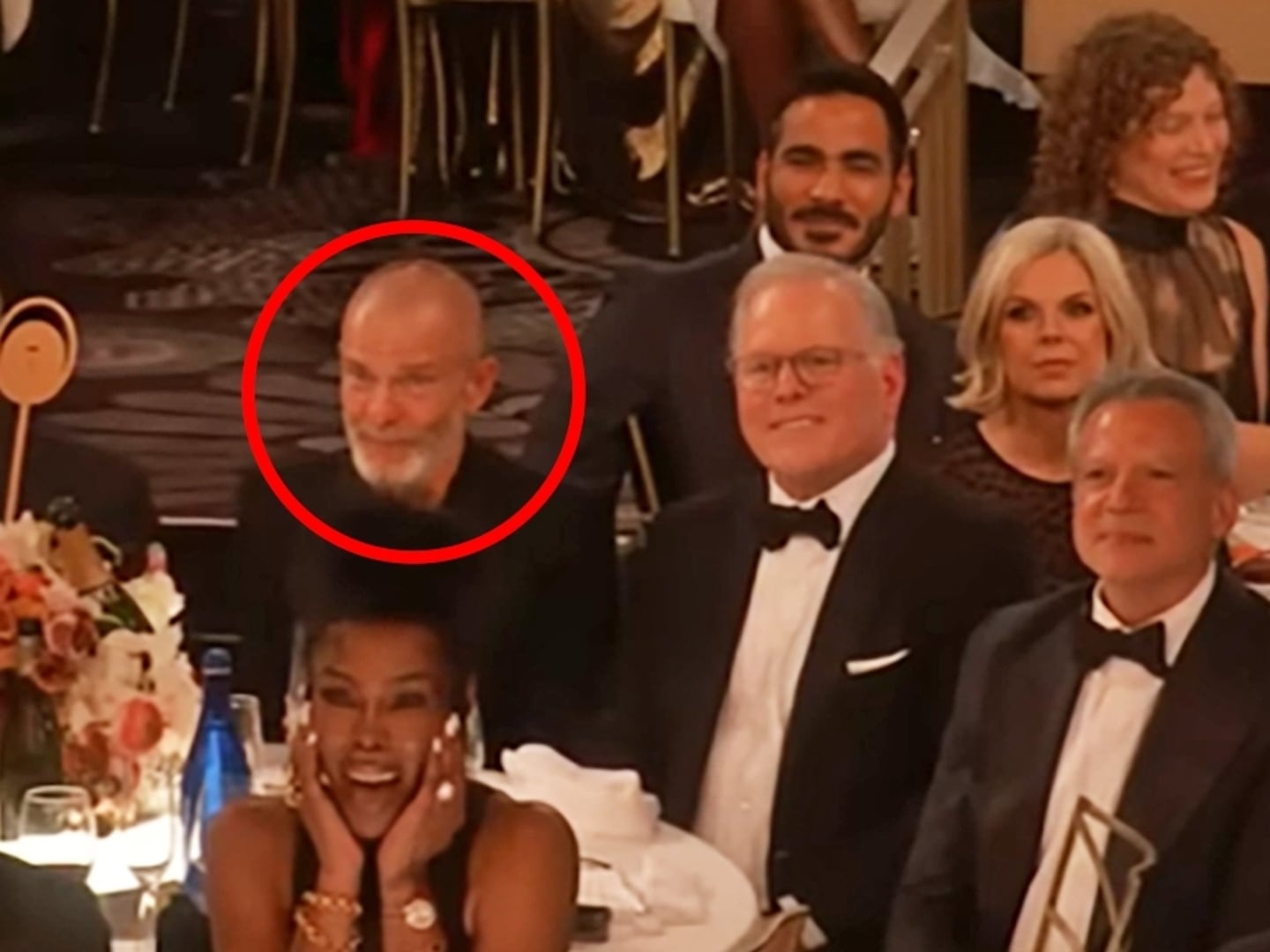

With no urgency and less action, the film slides into a trance-like state, replete with sequences involving an injured patio pigeon (a kindred trapped spirit!) and reveries and hallucinations in which Nemo navigates a hidden passageway, confronts the penthouse’s owner at a gala show, and is visited by the man’s daughter and dog as well as the cleaning woman whom he watches, on CCTV, going about her daily routines.

Inside has no interest in the thriller genre’s nuts and bolts, and consequently, it functions as more of a self-conscious—and COVID quarantine-friendly—acting exercise for its star. Dafoe melts down better than just about any performer alive, and his intensity is so great that Nemo remains a captivating presence even though we learn next to nothing about him, both via expository details (of which there are none) and his actions (which impart little other than that he’s reasonably creative and clever).

There’s electricity in Dafoe’s eyes and taut energy in his wiry frame, and watching him fret, fume and fight to maintain his sanity in this one-man show can be fascinating. Too often, however, Katsoupis’ film eschews the very sorts of scenarios that might jolt the action to life; for the most part, the director prizes vague ruminations on survival and art over engaging plotting.

“There’s no creation without destruction,” is Nemo’s final message in Inside, scrawled on a bedroom wall alongside various floor-to-ceiling sketches that intimate a mind in decaying disarray. Katsoupis’ own desire to demolish and deconstruct his familiar dramatic conceit, alas, reaps few rewards, save for the intermittently entrancing sight of Dafoe descending into madness and, in that abyss, discovering the path to transcendence.

Liked this review? Sign up to get our weekly See Skip newsletter every Tuesday and find out what new shows and movies are worth watching, and which aren’t.