Gaspar Noé is a renowned conductor of nightmares, and with Vortex, he takes a deep dive into realistic trauma and terror. The story of an elderly French couple battling burgeoning dementia, Vortex is something of a left turn for the Irreversible and Climax auteur, patiently charting its protagonists as they navigate harrowing final days full of confusion, fear, frustration, and mounting peril. Far less flashy and in your face than much of his prior work, Noé’s latest remains a formally bold and distinctive drama, employing a meticulous aesthetic design and two superb lead performances to craft a chilling portrait of the end times.

Given its subject matter (and its director’s mordant sense of humor), it’s fitting that Vortex begins with its concluding credits, as well as a dedication: “To all those whose brains will decompose before their hearts.” His protagonists—an unnamed couple played by legendary Italian horror director Dario Argento and actress Françoise Lebrun—are part of that group. He’s a long-time film critic and she’s a psychiatrist, the two residing in the flat that they’ve called home for decades. Following a shot-countershot sequence of the pair looking at each other from opposite windows, and then sharing a glass of wine and some food at a courtyard table—during which she remarks, “Life’s a dream, isn’t it?” and he responds, “A dream within a dream”—the film picks up with them in bed, where Lebrun’s wife awakens and, as she does, the frame literally separates into two equal square quadrants, thus creating a split-screen design that will be maintained for the remainder of this 142-minute affair.

Vortex’s bifurcated visual schema is Noé’s means of highlighting Argento and Lebrun’s escalating disconnection, a notion exacerbated by numerous instances in which the juxtaposed two are seen facing or moving in different directions. Since they continue to live together, this estrangement isn’t physical but mental, brought about by Lebrun’s dementia. That condition isn’t initially apparent as Lebrun goes about her morning routine of lighting the stove for her husband’s coffee, and as they pass each other while walking to and fro in their residence—all of this set to the sound of a radio broadcast about the grieving process. Yet it doesn’t take long for it to manifest itself, with Lebrun venturing outside to drop a bag of trash in the dumpster and wandering aimlessly through various nearby stores, the look of mystification on her face speaking volumes about the fog now enveloping her mind.

Argento locates his wife before calamity can strike, but an air of misfortune hangs over these proceedings, and not only because Lebrun’s malady is—as her spouse well knows—incurable, and therefore destined to worsen before it consumes her entirely. A later incident involving Lebrun leaving the stove’s gas on proves that the two are in danger due to Lebrun’s deterioration, and that turns out to be a concern not only for Argento but for the couple’s son Stéphane (Alex Lutz), who occasionally appears to help with minor mishaps and to try to convince his parents that they need assistance. Alas, those efforts are mostly for naught, with his mother generally lost in a fugue and his father stubbornly convinced that they can manage on their own, this despite the fact that Lebrun may be prescribing her own medication, giving her husband the wrong pills for his own serious heart condition, and apt at any moment to do intentional and/or unintentional harm to them out of a mixture of disorientation and despair.

That Lutz’s son is struggling with drug addiction and a chaotic personal situation—his wife is in a mental hospital, leaving him to care for his son Kiki (Kylian Dheret), all as he passes out free needles on the street to fellow users—only furthers the action’s turmoil. Vortex immerses itself in this domestic environment through parallel views that gaze, simultaneously, at Argento and Lebrun as they occupy the offices, hallways and bedrooms of their home, along the way finding flickers of compassion and camaraderie (notably, Argento crossing the split-screen divide to hold Lebrun’s hand). Slowly but surely, things are falling apart for this family, and the length, and music-free silence, of Noé’s extended takes evoke the burdensome weight of time, and the painfully drawn-out nature of this final phase. The director’s approach is attuned to the banal rhythms and longueurs of his characters’ circumstances, replete with edits—gentle blips that propel the material forward in unexpected intervals—that suggest, formally and thematically, the way in which life passes in the blink of an eye.

Although treading the same general terrain as predecessors like Away from Her, Amour and The Father, Noé’s Vortex is a unique contemplation of the edge of the abyss, where misery, dread and anger freely comingle. Since Lebrun’s mother is mostly adrift, those emotions are mostly felt by Argento and Lutz, each of them contending with their own particular anxieties: the former about his wife, his in-progress book on films and dreams, and his falling-apart affair with a long-time mistress; and the latter regarding his parents’ degeneration and his own precarious sobriety. Still, the longer it crawls toward its inevitable finale, the more Vortex feels like a showcase for Lebrun’s masterfully understated turn, the actress so fully inhabiting her befuddled matriarch—and imparting, through small, communicative gestures, her trapped-within-herself panic and self-loathing—that it’s often easy to forget that she’s giving a performance at all.

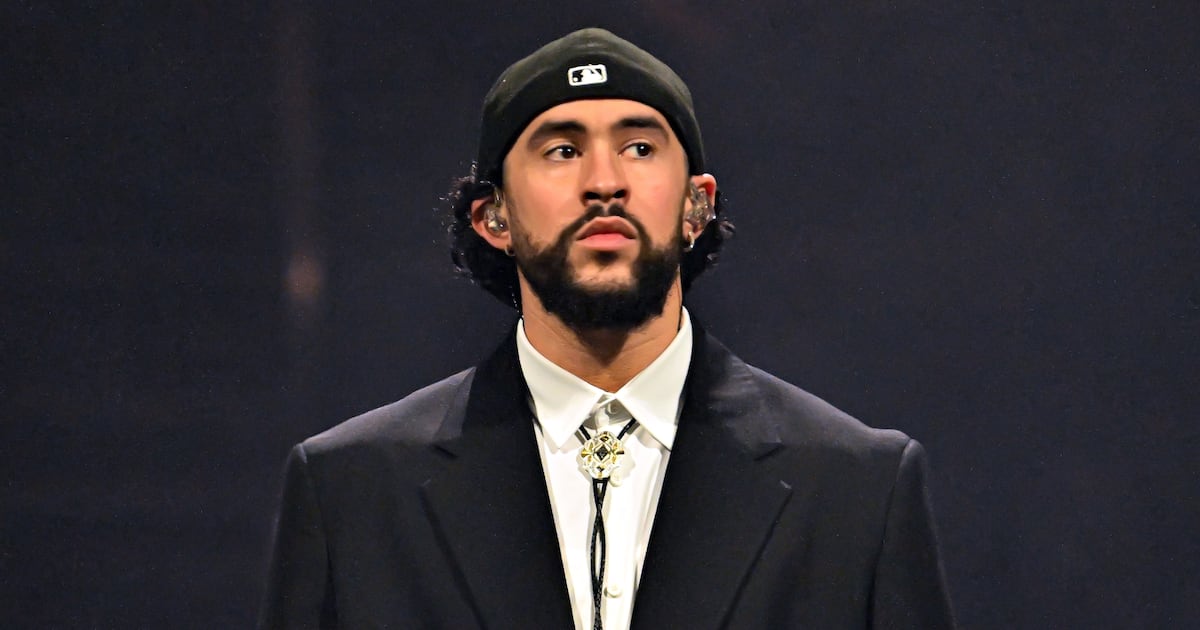

Dario Argento, Alex Lutz and Françoise Lebrun star in Gaspar Noé’s Vortex

UtopiaNoé’s roving camera tracks his subjects in intimate close-up as they shuffle about, doing their best to bide their time on their way into the void. His split screens at once tethering his characters together and isolating them from each other (and themselves), the director considers dementia with respectful honesty and candidness. Theirs is a twilight lived “scared” and “among drugs,” and destined to terminate in an awful fit of unseen suffering and loneliness, in the process leaving behind discarded objects, empty apartments, and a world that dutifully moves on without them. Noé captures this misery with understated grace and empathy. And with touches both overt and subtle—including Argento’s chatter about his book and the Metropolis and A Woman Is a Woman posters lining his home’s walls—he also conveys the inextricable relationship between cinema, life, and dreams.