Welcome to UNMISSABLE, the Daily Beast’s Obsessed’s guide to the one thing you need to watch today. Whether it’s the most gripping streaming show, the most hilarious comedy, the movie which you’ll never forget, or the deliciously catty reality TV meltdown, we bring you the real must-see of the day—every day.

It’s rare for a sequel to be genuinely surprising, and even rarer for one to wholly upend the expectations set by its genre forefathers and series predecessors.

That 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple (January 16, in theaters) does both is a feat almost as astounding as its finale, whose unholy heavy-metal majesty is so jaw-droppingly awesome that it’s bound to elicit outright cheers in the theater.

As a stand-alone post-apocalyptic thriller, it’s multiple cuts above. As the fourth entry in a long-running franchise (written, like its ancestors, by Alex Garland), it is, to borrow a phrase uttered by its protagonist, “miraculous”—and marks this zombie saga as a nightmare with few equals.

While she shuns the grainy DV/iPhone sheen of the Danny Boyle-directed 28 Days Later and 28 Years Later for cleaner, more traditional aesthetics, director Nia DaCosta—dropping her second triumphant behind-the-camera effort in months, following last October’s wildly dissimilar Hedda—brings plenty of majesty to her mayhem.

The film initially focuses on Spike (Alfie Williams) as he grapples with his new circumstances as a captive of Sir Lord Jimmy Crystal (Jack O’Connell), a Jimmy Savile-cosplaying psychopath in a tracksuit, gold chains, flashy rings, and a tiara. Jimmy’s gang is comprised of young men and women who wear identical long, stringy blonde wigs and call themselves “Jimmy.”

In an empty indoor pool, Spike is put to the test, forced to fight a fellow Jimmy to the death, the reward being induction into the crew. This goes well for the kid, but he’s hardly happy about his new clan, given that they’re lunatics who buy their leader’s prattle about being the son of Old Nick (i.e., the Devil) and fulfilling their destiny in this “hell” by delivering “charity” in the form of torture and murder.

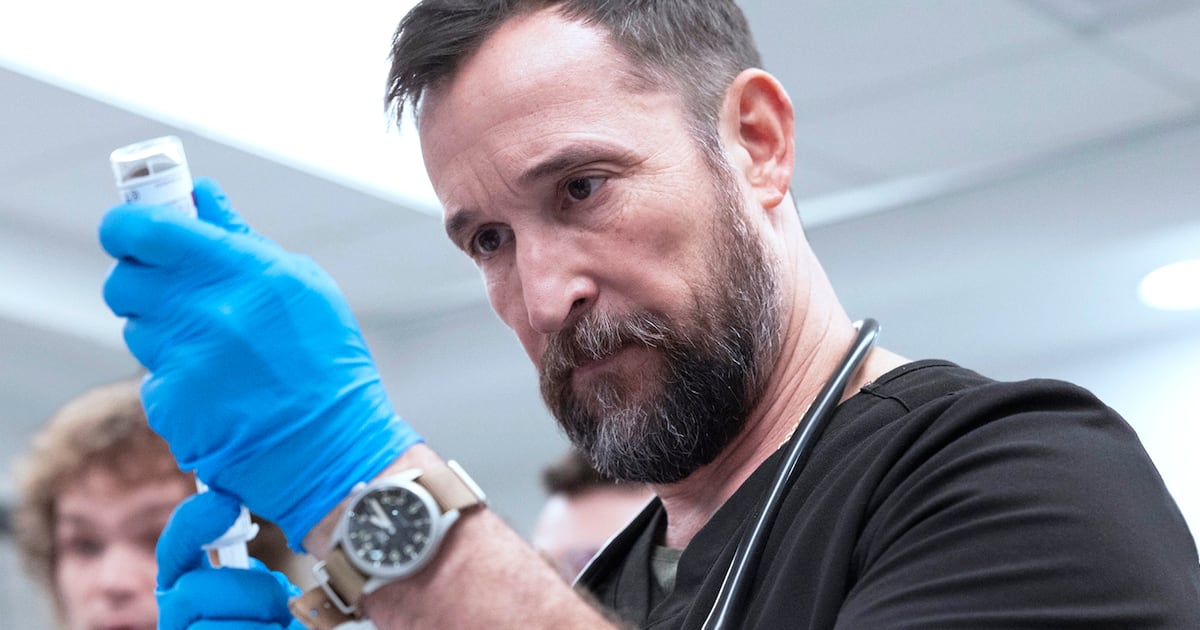

28 Years Later was a coming-of-age story about Spike’s maturation in a fiercely unforgiving world, and The Bone Temple is similarly fixated on evolution, albeit in decidedly different ways. As Williams’ pre-teen struggles to cope with Jimmy’s malice, Dr. Ian Kelson (Ralph Fiennes) continues his work at his skeletal memorial for the deceased—an imposing monument comprised of bone totem poles and a skull tower that he’s fashioned as the grimmest of ossuaries.

Of more pressing importance is Kelson’s rapport with Samson (Chi Lewis-Parry), a Rage-infected Alpha whose ferociousness is epitomized by his habit of felling victims by ripping their heads off their shoulders, the spine still attached. Samson is a nude goliath who makes his fellow zombies look benign by comparison. Yet in repeated stand-offs, Kelson learns that the gigantic fiend understands the nature of the blow gun and morphine darts being used to tame him—a discovery that implies there may be consciousness lurking beneath the infected’s uncontrollable frenzy.

The Bone Temple is, for long stretches, a bifurcated affair whose two halves are subtly in dialogue with each other, beginning with the juxtaposition of Jimmy’s Beelzebub dogma and Kelson’s scientific rationality. They’re two sides of an age-old coin, even as they prove to be equally flamboyant, with Jimmy a grinning demon prone to cackling as his minions carry out his depraved orders, and Kelson singing Duran Duran hits (“Girls on Film,” “Rio”) as he goes about his daily toil and relaxes, alone, in his underground domicile.

A close-up of Fiennes sitting on his bed as a phonograph plays and photographs of his prior self stare at him from the wall speaks volumes about the emotional and psychological toll the End Times have taken on him. Though he speaks with a clarity that suggests logic and stability, the actor captures Kelson’s madness in small, subtle looks and actions as he begins spending his days alongside the sedated Samson, trying to awaken a mind that seems trapped in a perpetual dream.

Be it a gorgeous master shot of Jimmy and his masked marauders in a barn that boasts a The Lost Boys-style widescreen grandeur, or a barbaric late skirmish featuring Samson and a horde of hungry attackers in a cramped train car, DaCosta helms The Bone Temple with confidence and flair.

And she’s matched, grand gesture for grand gesture, by Fiennes, whose Kelson, despite his fixation on “memento mori,” remains an optimist determined to see if he can initiate rebirth in this land of the dead. Garland’s script is rich with ideas about faith and reason, sadism and compassion, selfishness and sacrifice, and mortality and renewal, and it tackles them with bracing, live-wire unpredictability.

There’s never a moment during this odyssey when its outcome is foreseeable, with the writer taking one sharp left turn after another on his way to a conclusion that crashes its two threads into each other.

In that finale, The Bone Temple achieves a measure of Satanic splendor that’s breathtaking; DaCosta’s giddy staging and Fiennes’ go-for-broke performance (of Kelson’s own over-the-top routine) beget a showstopper as memorable as anything delivered by this sterling series. A collision of the sinful and saintly, the lucid and insane, it’s a headbanging triumph, and made all the more stirring for springing naturally from the preceding action and its underlying concerns.

With it, Garland and DaCosta allow the warring elements at play in this frenetic, habitually mutating franchise to have at it in a fundamentally dramatic manner that intimates that good and evil are natural forces as well as roles assumed by the benevolent and iniquitous alike.

As Fiennes’ foil, O’Connell reconfirms (after Sinners) that he’s ideally cut out for malevolent business. His Jimmy is a scarily cocky fanatic whose tall tales alternate between being about Lucifer and the Teletubbies, those creepy kids-TV favorites whose show was the last thing he saw as a kid before the zombies arrived (as seen in 28 Years Later’s prologue).

As a villain modeled after one of the UK’s most notorious icons, the 35-year-old actor taps assuredly into the material’s overarching portrait of innocence perverted, crafting a unique vision of cheery malignancy.

The film, however, refuses to wallow in his wickedness, and with a crowd-pleasing coda, it both reiterates its belief in decency and mercy as the ultimate path to victory, and thrillingly suggests—with a cameo that fans have long been waiting for—that this superb franchise has more territory to traverse.