On the basis of 2018’s Annihilation and now Men, acclaimed writer/director Alex Garland has become the master of jaw-dropping, brain-melting endings. Although if you ask him about the phantasmagoric finale of his latest, he admits that, at first, he found himself more than a bit disappointed by his lack of originality.

“With my daughter, I was watching this TV series called Attack on Titan. I was looking at the way the creatures in Attack on Titan, which all have human forms, are represented, and I was thinking this is so strange and inventive, and I’m just being lazy. This body-horror transformation thing—I’m too familiar with this. I know how it’ll end up looking,” he states shortly before the film’s May 20 theatrical premiere. “Attack on Titan takes naked human forms and does something really unsettling by not doing very much. And it was that. I thought, come on man, you’re not doing well enough!”

No matter such self-recriminations, Garland most certainly does well enough with Men, a harrowing and hallucinatory horror story about Harper (Jessie Buckley), a young woman who takes up temporary residence at an English country estate in the aftermath of a mysterious traumatic incident involving her husband (Paapa Essiedu). There, she’s shown around by the manor’s owner Geoffrey (Rory Kinnear), a cheery fellow with slightly messy hair and large teeth. Before long, Harper encounters a collection of additional, less welcoming males, from a scratched-up naked stranger in the woods, to a dodgy gray-haired vicar, to a nasty adolescent boy. More unnerving still, while Harper doesn’t seem to overtly notice it, all of these men boast the same Rory Kinnear visage.

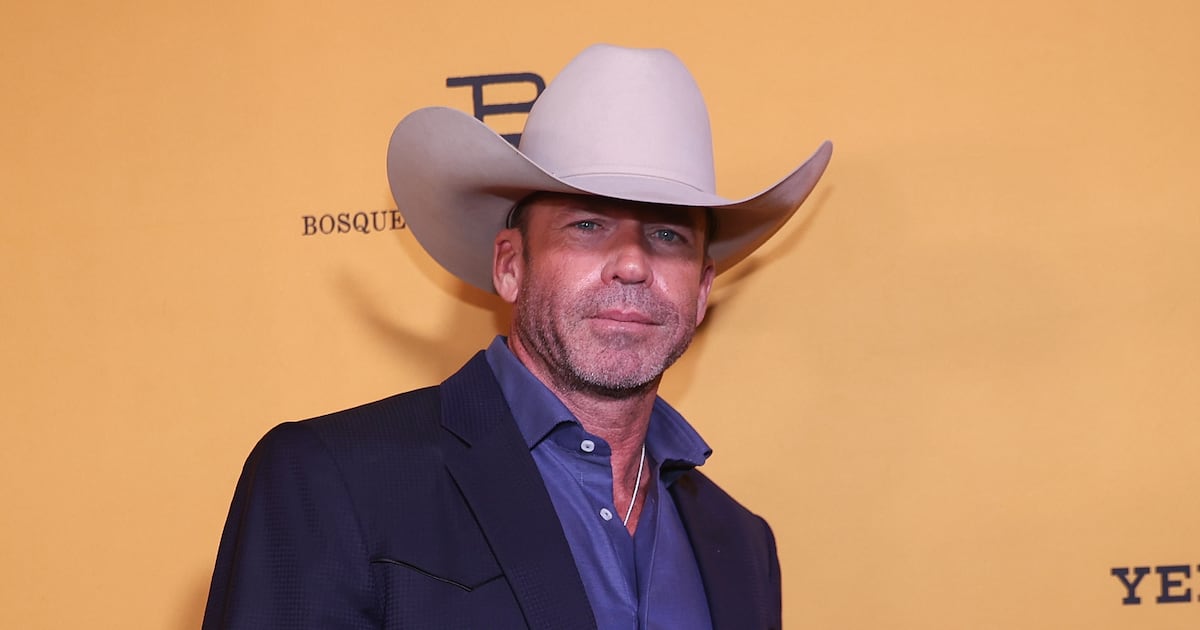

Rory Kinnear in Men

A24Likely best known stateside for Penny Dreadful and Black Mirror, the exceptional 44-year-old British actor thus proves to be the embodiment of various types of toxic masculinity. Yet Kinnear is quick to point out that the film is, fundamentally, a highly subjective portrait of that larger sociopolitical subject. “The film centers around one woman’s experience, and it is one woman’s experience of all the trauma in her life and how that plays out in the way she interprets male behavior on this particular holiday. We’re not trying to say that this is a universality of female experience; it’s this character’s experience,” he explains. “But we’re also trying to say, maybe to some men, that there are aspects of male behavior that goes unchecked, that maybe we don’t examine or explore ourselves, however well-meaning. Certainly, with the Geoffrey character, I think when we first meet him his behavior is essentially well-intentioned and generous. But often, he gets it wrong, and it becomes, however small, an unpleasant experience in the way that minor aggressions are a part of female life.”

Ask Garland about the charged topic tackled by Men, and he responds, “It’s a bit like the Attack on Titan thing—the answer is less good than the question. Honestly, I wanted to write a horror movie about a sense of horror. I knew I wanted to do that. I understood the sense of horror, and I thought, a horror movie is an interesting way to investigate that. Then with the title, I just thought it’s so perfect—the word ‘men,’ how compact it is, and how freighted it is. If you’re talking about something that people can project into, that word’s got a lot you can project into. And I was thinking, someone has done this before. I started googling “men movie,” and I thought, right, I better grab it, because there didn’t seem to be one—or if there was, I couldn’t find it.”

Men’s setup is beguiling but it’s its ending that will leave people exiting theaters in a state of shock and awe, and it solidifies Garland as an artist with a gift for delivering unforgettable knockout punches. The auteur concedes that, “I quite like doing that, maybe just instinctively, but it’s not a decision. It’s just organically how it works out.” No matter the source of Garland’s inspiration, Kinnear proclaims it “a bold move. When I first read it, it was a different ending, and I wonder if he always had it up his sleeve that he’d change it to this ending, once I’d signed on [laughs], or if it developed in his mind as he talked to us.”

Jessie Buckley being directed by Alex Garland in Men

A24Garland grants that “in the original script, the ending was a series of mutations rather than a series of births.” As for shooting the soon-to-be-infamous closer, “it was mainly a question of, you found yourself at four o’clock in the morning with not much on, lowing like a cow, and hearing these sheep respond from another field as if you were in some sort of communion with the natural world. And also, of course, dressed like a Teutonic green man figure,” he chuckles. “It’s one of those things where you say, there is absolutely no way of not committing to this. You can’t go and half-ass it; this absolutely requires 100 percent here. It was basically a week that that sequence was shot, and I just knew that by the last character, I would be inside, and it would be a bit warmer—and that sort of kept me going.”

He continues, “In terms of the effect, I had no idea what it was going to look like; it’s obviously very difficult to picture how it’s going to look, because a lot of it is left to after the event, with CGI and stuff. But each character was birthed in a specific way and had a specific reaction, and they were trying to get something specific from Harper, and that was my choice; that was what I wanted to do with each one. Each one represented someone trying to get something from her, and needing something from her, just as her husband was needing something from her at the end as well. So, it was playing those different beats, and how would each character try to seduce her—not necessarily sexually, but how would they seduce her to do something to make her love them, basically. That’s how I thought my way through it, in terms of what the whole means.”

Men’s terror and madness builds gradually, with Buckley’s Harper losing her bearings in this solitary locale, where thoughts of her spouse are inescapable. In this warped scenario, Kinnear is clearly personifying a very gendered brand of horror, even if that wasn’t the way he viewed the material. “It wasn’t a question of necessarily finding the malevolence within myself and within each character that was our jumping-off point. It was more a question of working out which particular route all these individuals had taken to be the people who they seemed to be in Alex’s script,” he says.

For Kinnear, Men was the fourth time in the last six years where he played multiple versions of himself in the same scene (including in the recent Our Flag Means Death)—a realization that made him think “that was quite an unusual niche to have found for myself.” Still, the key to his performance was seeing past his characters’ representational qualities in order to envision them as distinctive, three-dimensional individuals.

“You read the script and see what Alex is doing here, and why he’s using these particular positions of authority that they’ve been afforded. But I couldn’t think of them like that; I had to try to flesh out the characters as fully as possible,” he confesses. Consequently, “I tried to make sure, before the shoot, that I’d given each character the same amount of time of development in my head. And with hair and makeup, we weren’t saying, Geoffrey is going to be on camera more so let’s focus on him. Each one was given equal weight. But obviously, playing Geoffrey more than all the other characters, you got to know him a lot better.”

Technical trickery notwithstanding, Garland didn’t see the venture as very different from any other, since “I think probably 80% of my day, in a way, is logistics. It’s how do we arrange this thing to happen at this moment, and shoot this moment in such a way that the cameras are not off-putting to the actor, and capture the performance in as clean a way as possible. I think people always think directing is sort of like, moving in and giving an inspirational note to an actor and then stepping back, and I don’t do much of that. I see myself as like a manager. I’m just trying to keep it moving, often to stay out of other people’s way. Trying to stay out of the actors’ way is a lot of what my job is.”

Playing every man in Men did, however, invariably pose challenges for Kinnear, whose approach boiled down to “pretty much the old football manager phrase about taking each game as it comes. And it was only really that pub scene in which I would play two characters, and sometimes three, in one day. Most of the time, you had a few days as the vicar, or as Geoffrey, or whatever it was, so you were able to wake up and know who you were being that day, and be able to concentrate on that. It only got tricky in the pub scene, when you’re basically trying to dash between farmhands or dash between the landlord and the policeman.”

There’s a visceral quality to Men that’s new to Garland’s work, and which had apparently been percolating for some time. “I’ve been circling stuff for ages having to do with arguments in films, and how you make an argument,” he comments. “And also, the funny tension there is where people see what they want to see, to an extent, and read what they want to read—which is why you get two people, good friends, who read the same book and disagree about a character’s intentions or motivations. It’s really a reflection on the person reading it as much as the novelist. I thought I’d lean into that. I’m actually doing virtually the same thing on the film I’m making at the moment [Civil War, with Kirsten Dunst]—that’s explicitly to do with politics, whereas this is, I suppose, political, but not explicitly about politics.”

Further contributing to Men’s otherworldly ominousness are frequent nods to the Old Testament, beginning with Harper taking a bite out of an apple hanging from a tree in the house’s front yard. Garland acknowledges, “There’s a biblical element, but it’s the other way around, right? Why is that stuff in the Bible? It’s not generated by the Bible; the Bible is generated by it. There’s a centuries-old, millennia-old conversation/state of affairs/set of positions, and any number of different things, and what’s it generated? [The Bible] is sort of generated by that.”

Jessie Buckley in Men

A24Men is a work that’s at once highly specific and nightmarishly oblique, and that marriage is ultimately central to its disquieting power. Avoiding tidy explanations for its insanity, it dispenses bewildering imagery at every turn: a stone totem with carvings of ancient male and female figures; a tunnel whose entryway suddenly boasts a door; and a WTF climax of unholy metamorphosis. Refusing to proffer concrete answers to the layered questions it raises about male-female dynamics, it proceeds toward its ultimate confrontation with a strain of malevolence that vaguely recalls Lars von Trier’s Antichrist, albeit with a gut-punch menace and head-spinning opaqueness all its own.

Despite refusing to hold its audience’s hand, Men wasn’t, according to Garland, a difficult project to get off the ground—a change from his earliest cinematic endeavors. “I think the films I wrote always seemed different on the page than they were when they were finished. I had a very long history of making a movie and then delivering it, and the distributor—this will sound like a veiled insult about distributors, but it’s not really—read the script and thought it was going to be one kind of film, and then they got a different kind of film. And yet, I’ve shot what’s on the page, so they can’t say, hang on a minute, this isn’t the ending. It’s like, they return to the script and go, oh god, that’s what that line meant.”

“In Devs and in Men, I think the distributor and the financier knew what they were getting into, so they didn’t mind that stuff; I don’t think they did, anyway. But in terms of being opaque, part of the point of the film is leaning into that thing I said about two people reading the same book in a different way—it’s to lean into something you can’t really avoid. You can spell everything out, but you’ll still have people engage their imaginations and come up with their own interpretations.”

Rory Kinnear stalks Jessie Buckley in Men

A24It was that very quality which drew Kinnear to Men in the first place. “What I loved about the script was how accessible and yet oblique it is. How, like a painting, it’s incredibly rich—there’s a lot to take out from it—but there’s no right answer,” he remarks. “I’ve only seen it once, but I found it has a cumulative effect, the whole film, which sort of requires a very, very bold ending. Obviously, there are horror tropes that it’s fitting in with as well, to deliver the shock at the end. To do something big. And yet it’s entirely within the keeping of the themes that have been threaded through the rest of the film, quite minutely and gently. A lot of people are going to react in a lot of different ways, and that’s interesting and rewarding as an actor, and as part of the creative process of the film. But it’s also the kind of film that I enjoy, that inquires of an audience rather than dictates.”

Or as Garland puts it, you can make a movie where fans argue, “‘Iron Man wept because this happened!’ ‘No, he didn’t; he wept because that happened!’ I mean, you can spell it out as much as you like, but I just thought, fuck that shit, I’m going full-tilt the other way. I’ll make a film which is like a projection canvas.”