To speak hate—be it personal slander, political vitriol, or zealous calls for fatwa, jihad, and intifada—is to court its real-world manifestation.

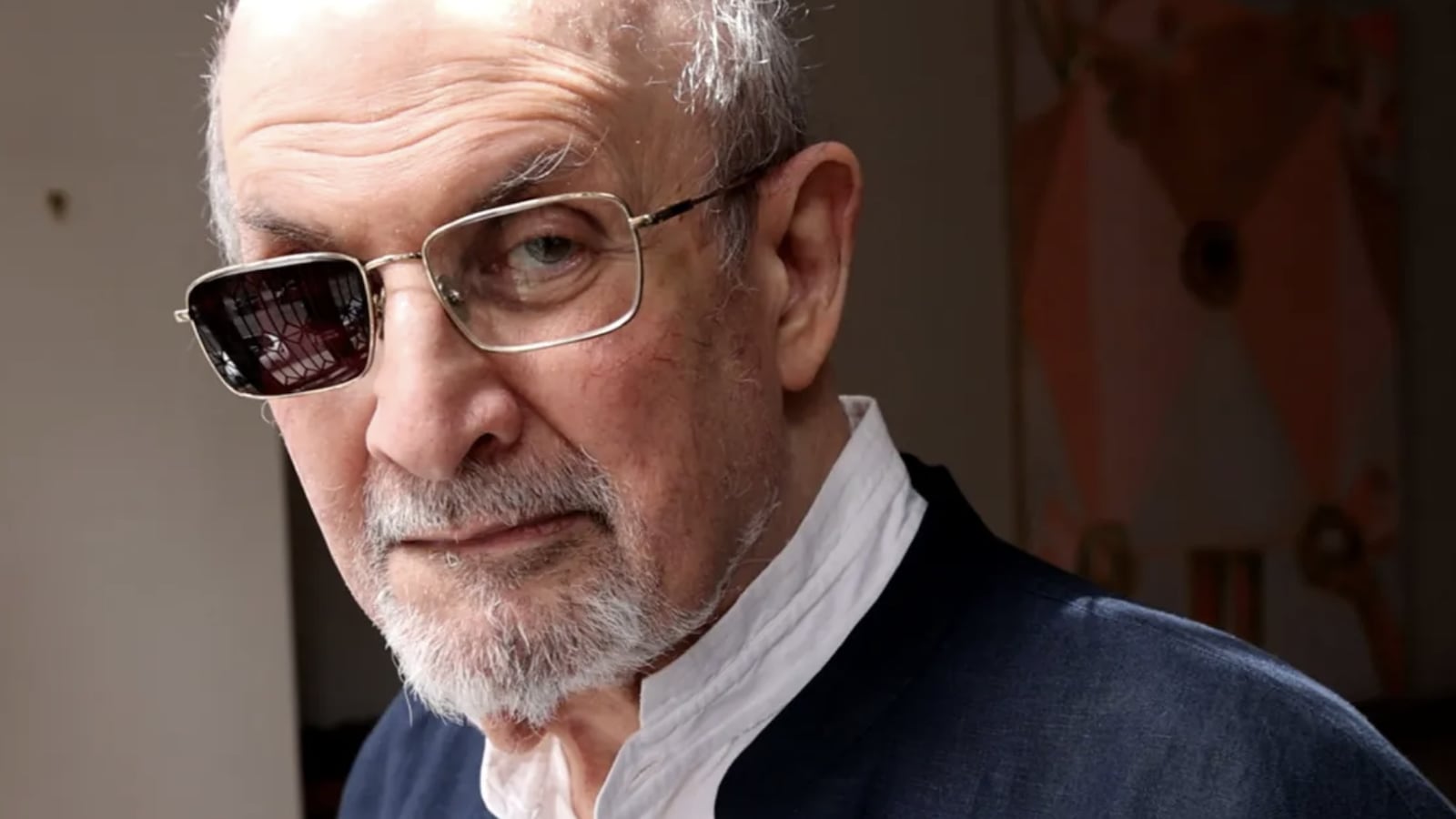

Since 1989, Salman Rushdie has been proof of this terrible fact, courtesy of the death sentence ordered against him by Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini over the author’s 1988 novel The Satanic Verses.

After years of failed assassination attempts, that threat became a horrifying reality on August 12, 2022, in Chautauqua, New York, when Rushdie was repeatedly stabbed in the neck, face, hand, and stomach by a 24-year-old New Jersey resident and nearly died.

It was an assault that underscored the devastating consequences of intolerance and fanaticism. And as illustrated by the intensely upsetting and inspiring Knife: The Attempted Murder of Salman Rushdie, the writer’s survival—for which the price was trauma, despair, and the loss of his right eye—is a stirring testament to both his resilience and to freedom as a vital bulwark against the forces of extremism and evil.

With piercing timeliness, Alex Gibney’s documentary—based on Rushdie’s 2024 memoir, and premiering at the Sundance Film Festival—recognizes that understanding violence (and the dangers it poses to individuals and society) requires witnessing it. Nonetheless, in one of the prolific director’s numerous shrewd decisions, he holds off on depicting the awful attack on Rushdie until the film’s conclusion, thereby heightening its heartbreaking impact.

Instead, Gibney begins on Day 4 of Rushdie’s recovery in an Eerie, Pennsylvania hospital, his neck and stomach boasting giant stitched-up wounds, his hand a punctured mess, and his gruesomely inured right eye bandaged. He looks, in many respects, like a Frankenstein-ian creature clinging to life, and the severity of his circumstances is italicized by a video of his tearful wife, Rachel Eliza Griffiths, cursing his assailant as a “f---ing monster illiterate piece of sh-t” who “chose violence.”

Rachel’s home movies of Rushdie’s rehabilitation are the backbone of Knife: The Attempted Murder of Salman Rushdie, providing an intimate view of the author’s struggle to heal himself both physically—an arduous process that involves having his eyelid stapled shut and regaining use of his left hand—and spiritually.

The latter is arguably an even more difficult task, considering that this near-fatal incident once again calls into question the possibility of ever escaping the Shah’s fatwa. In a bed that he can’t initially leave, Rushdie discovers all the old fears rushing back, as well as new doubts about his decision, during the past twenty years, to reclaim his life by living it publicly, using his media stature to acclimatize the world to the idea that he was, finally, safe.

Knife: The Attempted Murder of Salman Rushdie is a documentary about the power of words to destroy and to create, the former demonstrated by Khomeini’s denunciation—which, archival footage shows, led to mass-hysteria protests, bookstore and newspaper office fires, murder, and ultimately this attack by a perpetrator Rushdie refers to as “The A”—and the latter by Rushdie’s prose, including that which he reads in voiceover.

Through a recap of his backstory as a kid in Bombay, a student in the UK, and a notorious celebrity in London and New York, the writer explains that, in contrast to his Islamic enemies, his faith lies in storytelling, which, at its finest, employs the unreal to find the real.

The connections between Rushdie’s novels and his decades-long plight are beautifully suggested in Knife: The Attempted Murder of Salman Rushdie via a deft mixture of past, present, and animated material. Whereas his would-be killer used a blade to annihilate, the author states that writing is his (figurative) knife, cutting through the noise of the world to enlighten, to entertain, and to locate and expose the truth. Gibney’s doc does likewise, its form drawing parallels and evoking sentiments with the same incisive flair as Rushdie’s work, all while staying focused on his efforts to cope with what has taken place and salvage what he’s lost.

“If you’re turned into an object of hate, people will hate you,” states Rushdie. Yet whether he’s talking about the necessity of free speech or praising his beloved New York City (and his longing to again be a full-participant member of it), he’s a stirring figure of courage, tenacity, virtue, and good humor in Knife: The Attempted Murder of Salman Rushdie. Echoing his subject’s free-association thoughts while in the hospital, Gibney peppers his film with clips from The Seventh Seal and various knife-centric classic movies (12 Angry Men, Psycho, Knife in the Water, Un Chien Andalou), portraying Rushdie’s mind as a swirling repository of narratives and images.

His strength in the face of hardship is nothing short of rousing, as when he sanguinely opines, about this torment, and those which preceded it, “We would not be who we are today without the calamities of our yesterdays.”

Rushdie refused to apologize for The Satanic Verses and to bow down to his critics, including Roald Dahl, Jimmy Carter, and Yusuf Islam (aka Cat Sevens), whose song “Moonshadow (“And if I ever lose my eyes…”) is wielded brilliantly by Gibney as an ironic complement.

Similarly, Rushdie declines to play the victim in the aftermath of his recent ordeal. “What can’t be cured must be endured,” he intones, citing his late father, a lifelong abusive drunk. Endure he does, slowly getting back on his feet and out of health-care facilities with the aid of his loyal and supportive spouse. Even once he’s returned home, however, self-recriminations persist (“Had I made myself available for the knife?”), and it’s not until Day 401, when he and Rachel return to the scene of the crime, that some measure of peace and closure is attained.

Additionally detailing Rushdie’s alienation during his secluded, surrounded-by-security post-fatwa years (which rendered him a virtual hostage), Knife: The Attempted Murder of Salman Rushdie is a story about the various types of suffering brought about by hate.

It’s also, however, a moving portrait of the way in which such misery is fought and vanquished. In Gibney’s deft hands, Rushdie’s revival resounds as an example of heroic defiance, and his resumed career a beacon of hope. To quote the author’s remark about the body’s amazing recuperative capacities, which encapsulate the feelings his triumphant perseverance inspires: “What a piece of work is a man.”