“Not everyone’s past should be revisited,” pronounces Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis (Naomi Watts) to her daughter Caroline (Grace Gummer) in Love Story: John F. Kennedy Jr. and Carolyn Bessette. On the basis of the first installment of Ryan Murphy’s newest anthology—this one about real-life celebrity romances, for which he serves as executive producer—that certainly applies to his latest subjects.

Exceedingly watchable despite being slight, repetitive, and often campy, Murphy’s attempt at elevating John and Carolyn’s courtship and marriage into the stuff of fairy tale myth is like an even shallower version of The Crown, complete with impressive lead performances incapable of enhancing inherently skimpy material. Decrying tabloids even as it embraces their peek-behind-the-curtain spirit, it’s a People magazine feature in TV form.

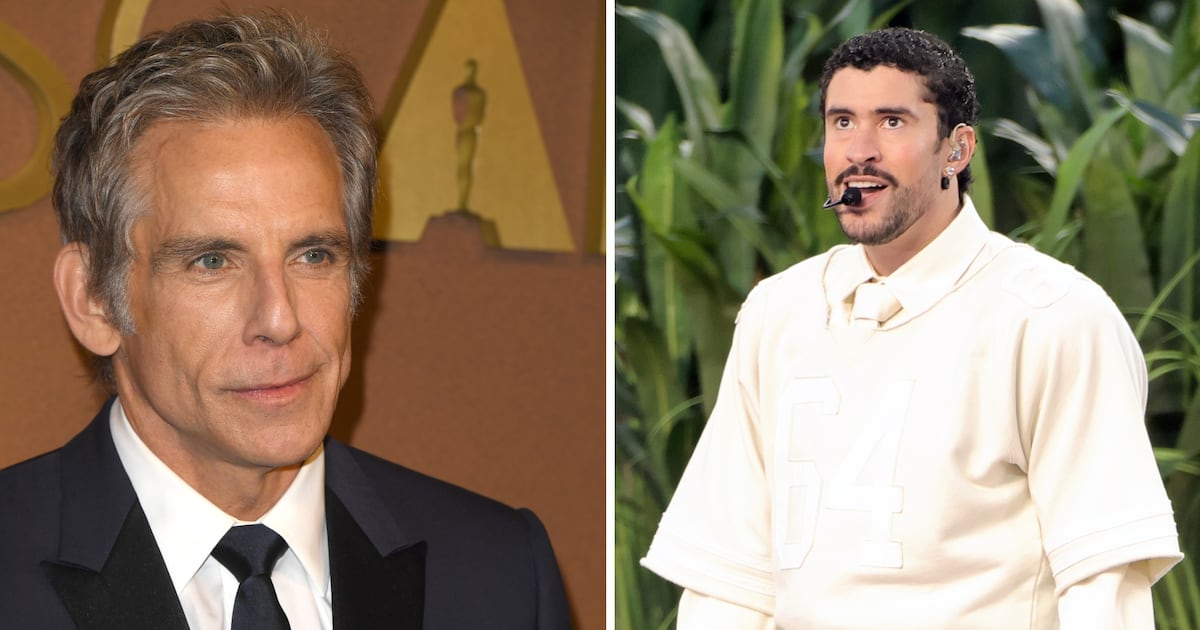

The best thing about Love Story: John F. Kennedy Jr. and Carolyn Bessette (February 12, on FX) is its stars Paul Kelly and Sarah Pidgeon. The former is a newcomer who doesn’t just look like John-John but captures his unassuming playboy charm, ego, and immaturity. The latter envisions Caroline as an equally formidable presence and partner in this high-profile relationship.

Both Kelly and Pidgeon craft their characters in three dimensions (unlike their ceaseless front-page photographs), digging deeply into the stew of expectations, ambitions, fears, and challenges that invariably complicate their highly unique circumstances. They’re as convincing and compelling as some of their compatriots are not—namely, Alessandro Nivola as a blandly imperious Calvin Klein and Watts as Jackie O in a thickly accented, speechifying turn that plays as Kennedy kabuki.

Inspired by Elizabeth Beller’s book Once Upon a Time, Connor Hines’ series is an even-handed look at the headline-making duo (who tragically died in a 1999 airplane accident along with Carolyn’s sister Lauren). Nonetheless, it leans slightly in Carlyn’s direction, striving to sympathetically set the record straight by dispelling some of the nastiest accusations leveled against her regarding drug abuse, her desire for children, and her loyalty to her husband.

That’s a shrewd narrative tack since it’s Carolyn whose life is upended by this unlikely love affair, the seeds of which are sown in 1992 when, while working as an up-and-coming talent for Calvin Klein, she’s introduced by her boss to John and sparks fly—a moment that, as with much of the proceedings, is enriched by the actors’ genuine chemistry.

Still, it’s not an obvious match made in heaven, given that John is in an on-again, off-again relationship with Daryl Hannah (Dree Hemingway) and smarting from failing the bar exam for the second time, and Carolyn is dedicated to a casual party-girl lifestyle that involves sleeping with future male model Michael Bergin (Noah Fearnley).

Love Story is most surefooted in the characterization of its main characters. In Kelly’s capable hands, John is a magnetic down-to-Earth hunk who’s also a wayward man-child shackled by his past and in search of who he is and what he wants to do. Pidgeon, meanwhile, embodies Carolyn as tough, independent, and driven, not to mention keenly aware of the numerous potential downsides—personally, professionally, and maritally—to being with John.

Love Story loves to tell rather than show, but its writing is, on the whole, reasonably adept, save for its early passages with Jackie O, who never stops yammering on about family legacy, responsibility, and what it means to be a Kennedy in a media-saturated world. Her matriarch frequently drifts into caricature, and Watts appears to be operating in a different show from those around her. As Caroline, Gummer is hamstrung by scripts that habitually reduce her to a cold, unfeeling scold.

They’re merely foils, however, for the series’ protagonists, whose interpersonal dynamics—and, specifically, struggle to maintain their love in an incessant, round-the-clock paparazzi and New York Post spotlight—are authentically dramatized.

Hines’ series is more than a collection of Page Six rumors, but it also aims to entice by imagining the private lives of the rich and famous. Though it says what it has to say reasonably eloquently, it hammers the same points home (about fame, obligations, and ancestral pressures) to diminishing returns.

Murphy productions are rarely subtle, and Love Story is no exception, regardless of Kelly and Pidgeon’s heroic efforts to occupy the thorny spaces where John and Carolyn intersect and diverge. Half the budget appears to have been spent on a soundtrack that features innumerable ‘90s chart-topping hits, and there are a few catty digs at luminaries of the era, be they Hannah (who’s portrayed as a needy, whiny, selfish nuisance) or Mark Wahlberg, who’s outright slammed in an early episode as a homophobe.

Perhaps the biggest problem with Love Story is simply that, for all its talk about John and Carolyn as de facto American royalty, they never feel as important as they’re treated. In the end, they’re just mildly interesting celebrities, most notable for John’s last name.

Furthermore, contrary to the series’ title, their romance comes across as not the stuff of storybook dreams but of nightmares, what with the endless media scrutiny and harassment, the titanic burden of the Kennedy clan and its “Camelot” lore, and the sacrifices required—particularly by Carolyn—to make this marriage work. Thanks to their situation, the duo’s pains to define their identities, alone and together, are unbearably arduous, and at a certain juncture, the primary takeaway from this tale is that stardom is overrated.

Even that, however, feels clichéd. And try as it might, Love Story can’t figure out a way to invigorate it, instead falling back on long-winded back-and-forths between its protagonists, complete with shouting, tears, and the occasional bit of make-up sex.

Worse, its action is urgency-free unless one fully engages with John and Carolyn’s emotional turmoil, and there’s not enough meat on this narrative’s bones to inspire such commitment. John and Carolyn seem like they were nice people forced to deal with a very difficult (if not outright impossible) reality. Yet the stakes here are too low, and the show’s stabs at making their story seem at once grand and whole—rather than cut horribly short, before any resolutions to their problems could be found—are clunky and unpersuasive.

Like The Crown, Love Story will be catnip for those who obsessed over John and Carolyn’s whirlwind amour and untimely demise. Ultimately, though, Murphy and Hines only manage to cast it as a sad footnote to a grander story.