A heroic origin story is coming to screens this month, and it’s not Black Adam or Black Panther. This one’s about a most unlikely supergroup of sorts: the musical heroes at the center of Meet Me in the Bathroom, the new documentary based on Lizzy Goodman’s 2017 book of the same name about the explosion of New York City’s indie rock scene in the early 2000s.

Fans of the book will recall its exhaustive, juicy account of how bands like The Strokes and Yeah Yeah Yeahs were heralded as the punky rock gods who freed us all from the brutally lame nu metal and glossy teen pop then monopolizing the mainstream. The film, from directors Will Lovelace and Dylan Southern, offers an enthralling look back at those golden years of musical purity and youthful debauchery, while also reminding us that the heroes we hailed as impossibly cool were also human and, in many cases, just kids.

For Goodman—who spent seven years writing Meet Me in the Bathroom and interviewing over 200 people for it—she wasn’t even sure she would ever finish her book, much less see the story make its way to the screen. But when she met Southern and Lovelace—a pair of British music doc pros who’d previously helmed the 2010 Blur film No Distance Left to Run and the 2012 LCD Soundsystem film Shut Up and Play the Hits—she knew they’d be the perfect fit for bringing her self-described “sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll youth story” to life.

“The most important thing was that it felt that the film was not burdened by a sense of having to justify its own value, which sometimes happens when there’s a legacy to uphold,” Goodman tells The Daily Beast. “I wanted it to feel young and like a portal to a lost time, but not obsessed with talking about how we’re making a portal to this lost time. And there is a certain earnestness that comes along with that. You have to be willing to trust that taking the problems of 20-year-old drunk children who want to be famous, who want to make amazing music, you have to take seriously their troubles and their story arcs. You have to take seriously the idea that being on the road is really hard, or the internal dynamics between bands are really hard. And when you’re one of those people, it feels a little pretentious to do that. You feel like, is it obnoxious to be centering ourselves in this way? Will and Dylan suffer from none of that. I really liked that [they] had this perspective of being outsiders in the best sense. They were from somewhere else and they just loved this world.”

Turning a 640-page oral history into a 105-minute feature is no easy task for anyone, which is why Southern and Lovelace initially pitched Meet Me in the Bathroom as a four-part docuseries. But “it wasn’t the right time for the streamers,” according to the directors, so they refocused it as a film, narrowing the timespan of the story to about four years, as opposed to the book’s 10.

Karen O of the Yeah Yeah Yeahs recording in Brooklyn, New York.

Emily Wilson Photography/Utopia“When we drilled down to the artists who we thought we would concentrate on, the thing they had in common was they’re all coming-of-age stories,” Southern tells The Daily Beast. “And that was a really interesting way to look at it—these coming-of-age stories that all take place in this period just before the world really started accelerating and changing into where we are today.”

It’s why Southern and Lovelace open their film with an old audio recording of The Strokes frontman Julian Casablancas asking Yeah Yeah Yeahs singer Karen O if she likes Dirty Dancing. Karen responds by saying she loves that film because of the “fantasy” of going away for the summer and stumbling “into this underbelly; this cool, sexy scene. And then you reinvent yourself”—not dissimilar to what she did as a twentysomething misfit who sought refuge and camaraderie in the dingy East Village bars where she eventually remade herself into an electric performer.

“That was the sort of ethos of the film, really,” Southern explains. “And just how long can that last? Because we all have these moments in our life that you probably don’t recognize at the time as the moment. There’s that really nice line from Albert [Hammond Jr., guitarist for The Strokes] that says you have this amazing time and you don’t realize it and then you spend years chasing it and trying to get back that feeling. We wanted to evoke that feeling, that kind of moment where a spark was lit.”

The Strokes.

Piper Ferguson/UtopiaEven with the film’s narrower focus, it does attempt to cover a lot of the big high-concept themes that the book does, including generational identity, gentrification, the post-dotcom boom, and the anxiety of 9/11 and subsequent doubling down on, as Goodman describes, “pursuing youth and abandon to the max because of all this fear and instability and insecurity,” which influenced the sounds of many of these bands.

“All of those incredibly nuanced and complex themes that we were able to weave into the book, you do not have the space to do that in a film,” Goodman says. “But the benefit of that is that certain things come to the foreground that don’t have as much foreground space in the book. Like Karen’s idea of being the only girl in the room a lot of the time, and the confusion and alienation of that experience of being the girl in the band. So in that way, the idea of [the film] as a companion piece [to the book] makes a lot of sense to me. It’s not supposed to be a beat-by-beat retelling of 600 pages. I mean, if Ken Burns wants to get involved, then maybe we can do it. But short of that, no.”

A pre-Yeah Yeah Yeahs Karen O performance.

Toni Wells/UtopiaAfter Southern and Lovelace sketched out their story and picked their coming-of-age heroes, they were faced with the daunting but ultimately thrilling task of finding the archival footage to help tell that story. The filmmakers and their small team of editors and producers did loads of “detective work,” tracking down footage taken on camcorders by band members, their friends, and fans. They contacted journalists to ask if they’d kept their minidisc recordings of interviews done with these musicians, and scoped out old online forums to see who might have been at these shows and had a camera handy. They found a woman in Los Angeles who had a whole suitcase of undeveloped photos and tapes of early concerts, including early footage of The Strokes playing a song that was never released and that many fans might never have heard until watching the doc. They reached out to music video directors and got outtakes from videos like Yeah Yeah Yeahs’ “Maps,” scoring a shattering, single-take closeup of Karen O singing the final two minutes of the song while tears stream down her face.

Ultimately, the breadth of rare footage is the biggest highlight of Meet Me in the Bathroom. You see studio scenes of Interpol recording their seminal first album and LCD Soundsystem’s first-ever performance as a band in London (previously, only their second show had been available on YouTube). You also see intimate moments of real friendship and humanity: the guys from The Strokes happily swinging off of subway poles like little kids, and The Moldy Peaches’ Adam Green and Kimya Dawson jamming for their neighbors in their cramped apartment. In one particularly chilling piece of never-before-seen footage, Interpol singer Paul Banks is seen standing on the sidewalks of Manhattan on the morning of 9/11, watching the Twin Towers burn.

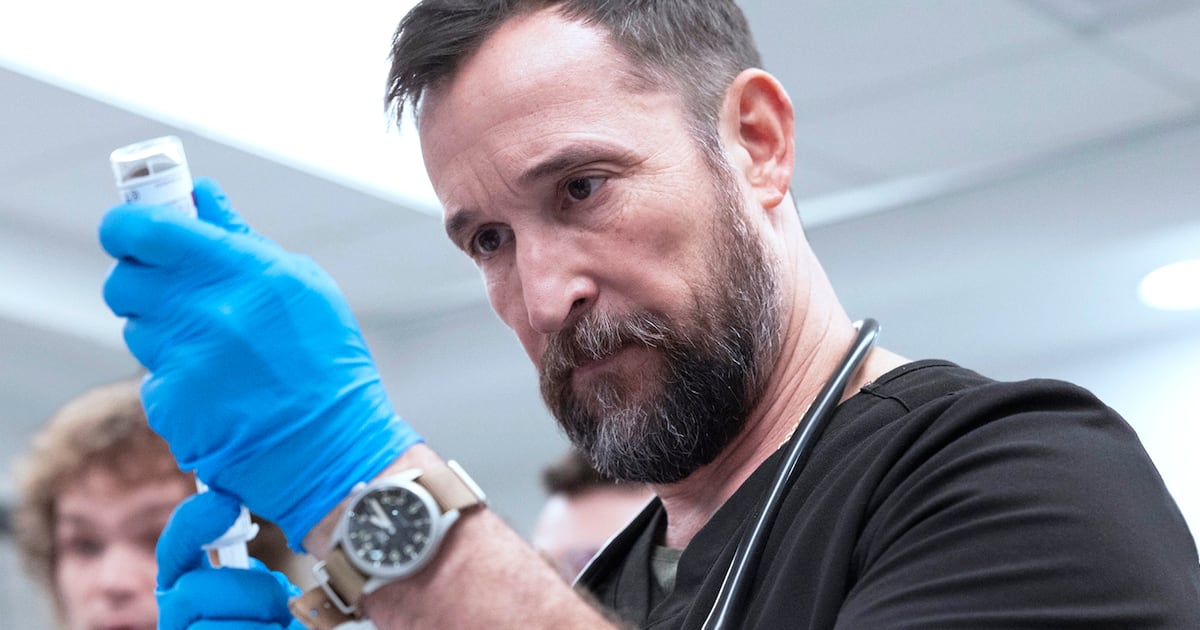

Interpol.

Josh Victor Rothstein/UtoipaAs it all unfolds, it feels like you’re actually stepping inside the dingy East Village haunts where these eventual era-defining bands were born. In that sense, the documentary doesn’t set out to analyze the scene so much as relive it; this is not a film that’s interested in contextualizing the era or trying to explain “what it all meant,” instead dropping viewers in and letting them live in that world for an hour and 45 minutes. Much like last year’s landmark Beatles documentary Get Back preserved the Fab Four in their youth, Meet Me in the Bathroom is comprised of wall-to-wall archive footage, featuring its key players in voiceover form but never letting us see them as they are now. The result is visceral: you feel Casablancas’ crippling anxiety about becoming famous, or James Murphy’s ecstasy at discovering dance music.

“We wanted to keep it as much in the moment as possible,” Southern explains. “That’s why there’s no talking heads and that’s why as much as we can, everything in the film comes from that period. It breaks the spell, really. I think it’s such an evocative time that it doesn’t help to see people our age looking back wistfully. It makes it feel more immediate and hopefully less retrospective.”

Goodman agrees, adding, “It’s a show-not-tell philosophy. This isn’t about setting in historical context ‘the meaning of the Yeah Yeah Yeahs,’ in some sort of NPR voice. This is about, you show what it felt like to be these people.”

The result inspires both nostalgia and jadedness in equal measure. Though the film creates a sort of mythology around figures like Casablancas, Murphy, and Karen O, their coolness feels frozen in time, especially as many of today’s young music fans’ interest in rock leans more toward emo and pop-punk. But Meet Me in the Bathroom is, at the very least, a reminder of how brightly they burned back in the day, and a suggestion that maybe—just maybe—that kind of lightning-in-a-bottle moment could happen again. After all, it’s during the doc’s opening moments, in 1999, when The Moldy Peaches’ Dawson says, “It felt like all that wild weird eclecticness had drained out of the city,” while her bandmate Green muses, “I remember thinking maybe New York isn’t the kind of city anymore that produces iconic bands.” We all know what happened next—the rock renaissance depicted so lovingly and frenetically in this film—so perhaps it’s never outside the realm of possibility.

“It doesn’t feel like you could have a scene that emerges as organically in a specific place now, just because we consume music so differently,” Southern theorizes. “But then one thing we always talked about while making it was how cool would it be if it inspired some kids somewhere to pick up instruments and make some music that nobody’s expecting.

“I’m really interested to see what the Gen Z audience makes of it all,” he adds. “I was thinking about it, when we were that age while this music was happening, it was 30 years since the Beatles. And now there’s been 20-something years since this. I find that both fascinating and depressing.”

Meet Me in the Bathroom will be shown in New York and Los Angeles on Nov. 4 before hitting screens nationwide for one night only on Nov. 8. It’ll then begin streaming on Showtime on Nov. 25.