The final segment of Resurrection plays out in a single, unbroken take that lasts a full half-hour, wending its way through a dock, town, and karaoke club on the last night of 1999.

Alternately coasting along as if on a ghostly breeze, and temporarily assuming the POV of a gangster named Mr. Luo (Huang Jue), who runs the enclave’s hottest spot, the film (December 12, in theaters) is a heady feat of virtuosic filmmaking, marked by jaw-dropping sleights of hand—the camera moving in and out of spaces with otherworldly ease—that speak to this import’s fascination with time, loss, and memory.

Imaginative and intoxicating, it’s arguably the crowning achievement of its maker’s still-young career.

Chinese auteur Bi Gan is no stranger to awe-inspiring oners; similar acts of stunning showmanship punctuate his prior films Kaili Blues and Long Day’s Journey Into Night. Nonetheless, there’s something unique and extraordinary about Resurrection’s centerpiece, whose deft navigation of locations and perspectives is complemented by its sneaky poignancy.

The tale of a twentysomething man and woman who meet on New Year’s Eve and strive to stay together in the face of violent threats from her boss and supernatural forces, it’s a tour-de-force of unbound creativity, its silky staging, enchanting performances, and playful inventiveness combining to make it one of the year’s undisputed big-screen highlights.

Resurrection concludes on a blissfully high note, although what precedes it is pretty great too.

For his third feature, Gan spins a tapestry of beguiling beauty and sorrow, indulging in his favorite motifs and preoccupations for a saga that purports to be science fiction but feels more akin to a hallucinatory fever dream about the movies. Starting with an exposition that confounds as much as clarifies, and finishing without lucidly answering most of the questions it raises, it’s a film that simultaneously challenges expectations and demands rigorous engagement. Those willing to go with its illusory flow and attune themselves to its hypnotic rhythms and swooning emotions are in for a cinematic experience unlike any other.

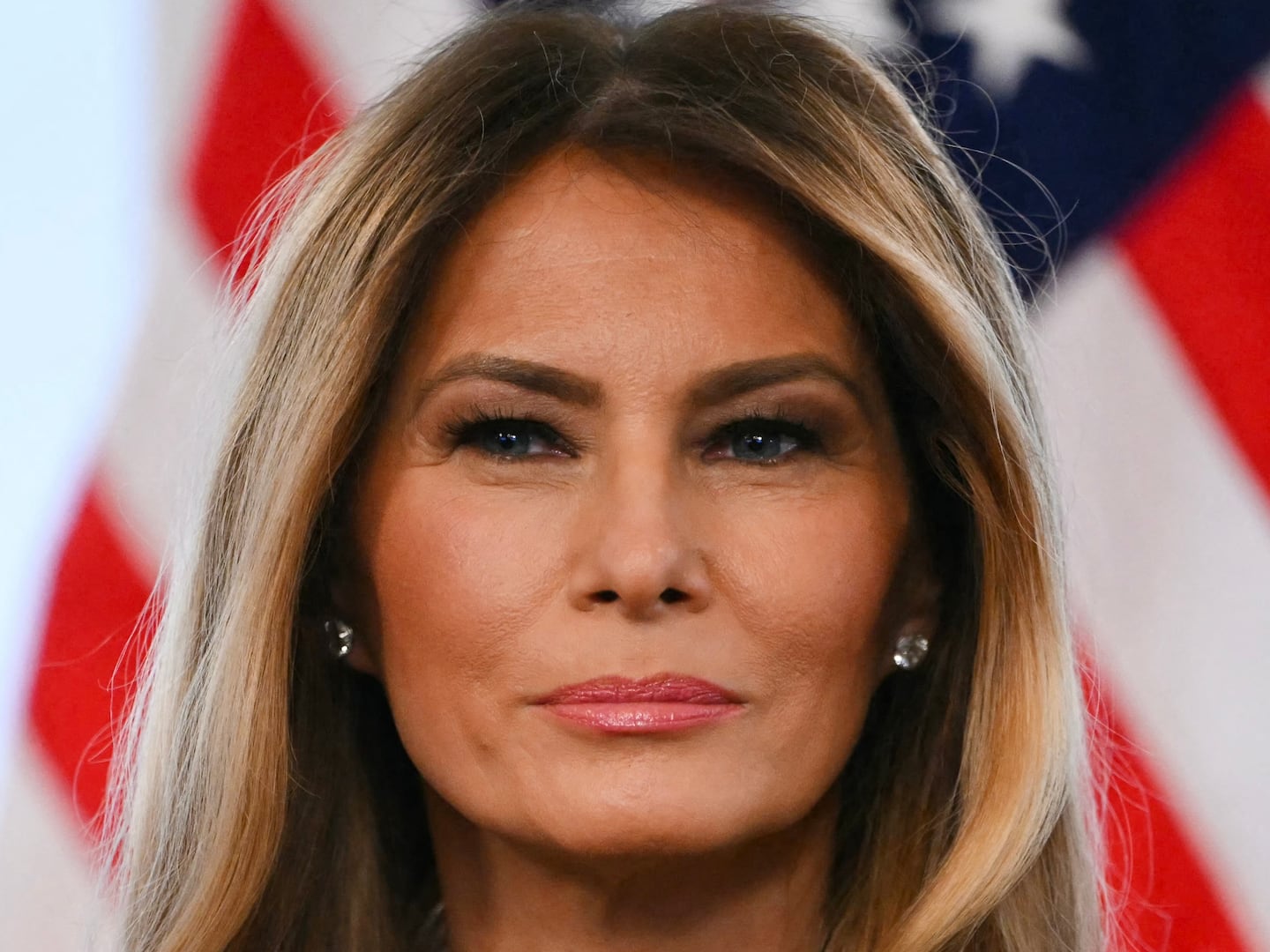

With old-fashioned intertitles, Gan’s latest lays out its conceit. In an unspecified tomorrow, humanity has achieved eternal life by forgoing dreams, and those few creatures who refuse to do away with their slumbering visions are known as “deliriants.” Miss Hu (The Assassin’s Shu Qi) is tasked with hunting and killing these individuals, and her current target is a figure hiding from capture in the ancient past of films.

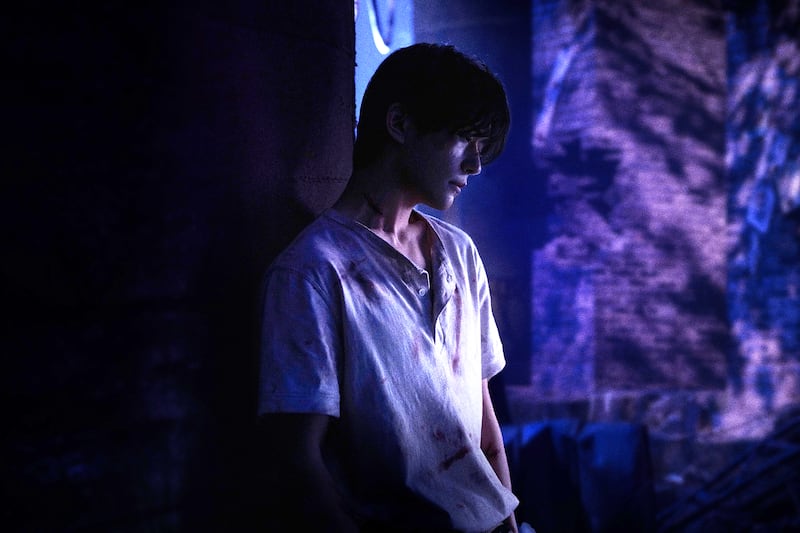

Thus, Resurrection commences in a silent movie (in a 4:3 aspect ratio) that resembles a macabre German expressionistic thriller, complete with an F.W. Murnua-esque deliriant “monster” (Jackson Yee) whose bald head, gaunt eyes, rotting skin, and hunchback physique are at once unnerving and clearly artificial—the byproduct, it’s ultimately revealed, of careful make-up effects. Such self-consciousness is par for the course in this opening salvo, with Miss Shu at one point crumpling up the screen, and things eventually taking a colorful The Wizard of Oz-style turn.

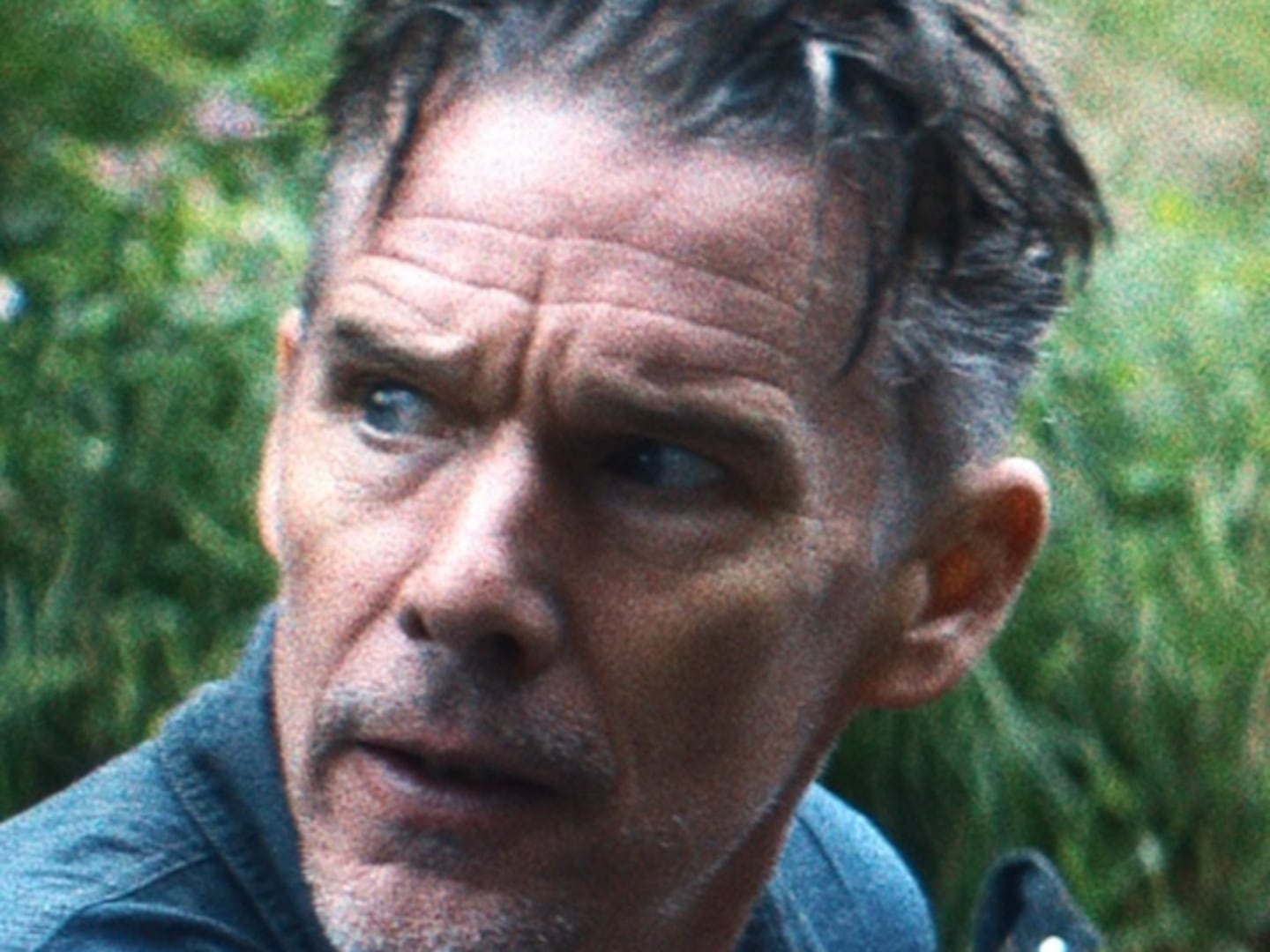

As evidenced by Miss Shu cutting the monster open to give him a new celluloid-reel heart, Resurrection is a meta-reverie about the silver screen. The deliriant subsequently evades his pursuer by leapfrogging into a widescreen scenario in which he’s Qui (also Yee), a brooder suspected by a detective (Mark Chao) of committing murder. Noir-ish crime drama is now the order of the day.

Yet despite the shift in genre, Gan tethers his material through recurring elements: mirrors, fog, fire, flowers, trains, cigarettes, water, and circular shapes and rotating motions that convey an interconnected sense of everything being both a beginning and an end. There’s harmony to the writer/director’s story, no matter that it’s often difficult to parse the meaning of his every gesture—a state of affairs that contributes to its haunting mystery.

Following Qui’s vignette, Resurrection fast-forwards decades to witness the deliriant, now a wretched man (Yee), have a prolonged nighttime conversation at a temple with the Spirit of Bitterness (Chen Yongzhong), who looks just like his father—a dynamic that stems from the fact that the deliriant conjured this apparition by knocking out a painful tooth with a piece of a broken statue.

Then, it concentrates on the deliriant as an urban conman (Yee) as he recruits an adolescent girl (Guo Mucheng) in a scheme to swindle money from an Old Master (Zhang Zhijian) by way of a sneaky card trick. In both instances, Resurrection grounds its action in grief and the attendant desire to revisit and recapture what has been lost. “Time rapidly fades away,” intones Miss Shu, and Gan’s film mourns its passing even as it attempts to turn back the proverbial clock via the magic of the movies, whose fantasies are conduits for our anguish and regrets, hopes and dreams.

Resurrection climaxes with the deliriant, operating as young Apollo (Ye), awakening in a boat to the sounds of fireworks, meeting a fetching woman who goes by Tai Zhaomei (Li Gengxi), the name of a 1980s Taiwanese singer, and trailing after her through a city populated by criminals, prostitutes, and New Year’s Eve revelers at the Sunshine Karaoke Bar, where they run afoul of Mr. Luo.

Just as his preceding split diopter shots play as homages to Brian De Palma, Gan’s gliding-through-windows camerawork recalls Michelangelo Antonioni’s The Passenger. Traces of David Lynch, Terry Gilliam, Tim Burton, and Jim Jarmusch are additionally sprinkled throughout. Still, there’s nothing duplicative about these proceedings, whose originality is palpable in every unexpected narrative left turn and dazzling aesthetic flourish. Only a handful of directors working today boast a command of the medium as breathtaking as Gan, and the 36-year-old artist pulls out all the stops in turning his quasi-sci-fi affair into a vortex of hallucinatory cinematic wonders.

A 21st-century remembrance of things past, Resurrection embraces traditional styles and conventions for a radical epic about the movies as a refuge for the lonely and the heartbroken, a vehicle for processing agony and generating ecstasy, and a time machine that allows for communion with yesterday and, with it, rebirth. Its plot adhering to a subconscious internal logic, it’s a mind-body-soul swirl of the real and the unreal, and Gan orchestrates it with the agility and confidence of a maestro.

His out-there opus may be steeped in the past, but its mad, mesmerizing power suggests he’s film’s future.