From Wake in Fright to Wolf Creek, Australia has been depicted in film as a wild and primal wasteland that punishes interlopers foolish enough to venture into its harsh outback.

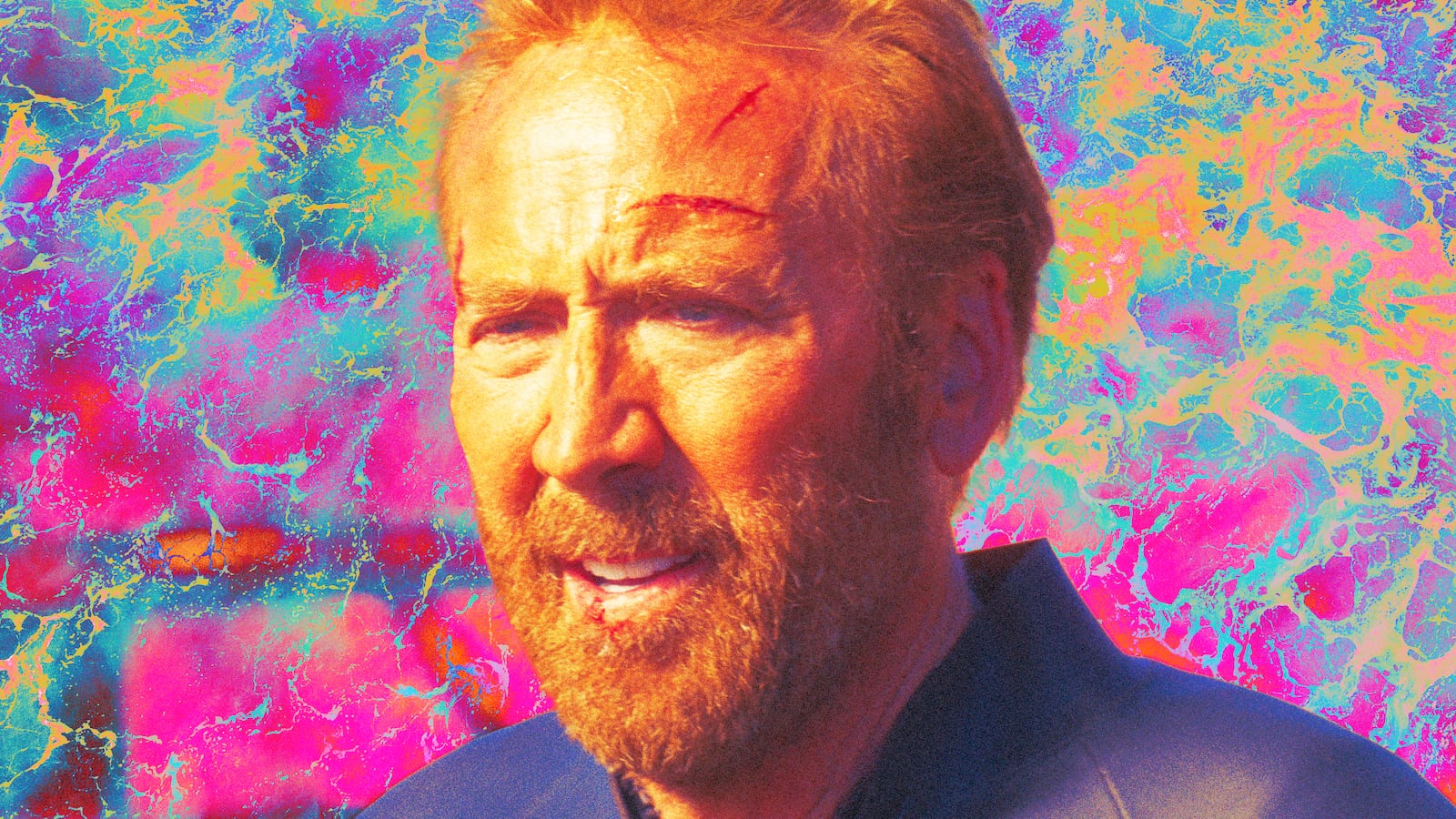

Nicolas Cage‘s unnamed protagonist is the latest cinematic character to learn that outsiders are unwanted Down Under, although the further The Surfer—a 2024 Cannes Film Festival selection in theaters May 2—proceeds down its trippy path, the more it becomes clear that the external threats he faces are less grave than those bubbling within.

Bleak madness is what’s on the menu in the Oscar-winner’s latest (as is a bludgeoned-to-death rat!), and Cage makes a meal of it, attuning himself to director Lorcan Finnegan’s wacked-out frequency to deliver another tour-de-force of grief, regret, anguish, and seriously psychotic fury.

Cage’s “Surfer” wants to hop on his board and catch a few waves with his son (Finn Little) at Luna Bay, where he’s trying to buy the cliffside house he grew up in with his father—all in the hopes of impressing his kid and, as is later revealed, winning back his ex-wife.

On their way down to the beach, however, Cage’s dad is shoulder-checked and cursed at by a fellow surfer—a prelude to the hostile greeting they receive from another local who, before they enter the water, screams at them, “Don’t live here, don’t surf here!” Before things get out of hand, a man in a red hooded sweatshirt named Scally (Julian McMahon) steps in and politely explains to the Surfer that the “Bay Boys” don’t tolerate strangers, and that it would be best if he swallowed his pride and departed.

The Surfer does, but he soon returns by himself in his Lexus, calling his mortgage broker to seal the deal on the house purchase. As it turns out, he’s now competing with another bidder, upping the Surfer’s anxiety. Director Finnegan echoes his frazzled state of mind by employing an array of smeary close-ups, bewildering snapshots of a mysterious figure standing in the surf, zooms into the blinding sun, a score of menacing tones and twinkling, and a deafening audioscape of chirping crickets, crashing waves, and squawking birds that sound as if they’re laughing at the man. From the get-go, The Surfer feels off-kilter, and it’s not long before it feels stricken with heat stroke—charred, scarred, and incapable of seeing straight or thinking clearly.

Thomas Martin’s script drops early clues that everything is not what it seems for the Surfer, such as a phone call from a coworker who asks him why he’s not in the office (he’s taken a “personal day”) and, more distressingly, why he led a meeting the day before in his bare feet. Even so, The Surfer plows forward without overtly explaining everything, with the Surfer objecting to a Bum (Nic Cassim) decorating his car windshield with a flyer regarding his missing dog.

The homeless man, who’s living in a messy Subaru hatchback with a flat tire, warns the Surfer about antagonizing Scally’s aggro acolytes, who gather nightly around the campfire outside their beach shack base of operations. That’s good advice, given that these bros are provincial territorial maniacs whose borderline-rabid behavior—often directed at the Bum—suggests that they’re ready for the Mad Max post-apocalypse.

The Bum blames Scally for stealing his son and killing his pooch, and he slanders him as a wealthy scion cosplaying as an alpha guru. In that regard, he isn’t far off, with McMahon’s antagonist coming across as a chauvinistic Aussie loon who believes that becoming a man—and attaining salvation (i.e., surfing)—is only possible via suffering.

Nonetheless, the Bum isn’t exactly level-headed, and neither, after a short while, is the Surfer, whose rivalry with these locals takes off once they steal his surfboard and, when he tries to retrieve it, scare him off with threats of violence. In response, the Surfer calls the cops, yet the responding officer (Justin Rosniak) is as repugnant as Scally’s disciples. The barista working the parking lot coffee stand is similarly cold and unhelpful, and between him and the Bum, the Surfer gives away most of his important possessions (sunglasses, watch, cell phone) in exchange for largely useless items.

With a quick early cutaway, The Surfer tips its hand. Still, it maintains intrigue by repeatedly veering between different realities. The result is that it’s difficult to get a complete grasp on the situation; as with his prior Vivarium, director Finnegan’s film is a disorienting head trip.

Spiraling, swirling pandemonium eventually engulfs the Surfer, and Cage evokes his descent with hysterical intensity, his ostensibly well-adjusted demeanor chipped away at by his tormentors and a natural world that appears to have it out for him. Cage is in his element as a man gripped by mounting rage, and the headliner casts the Surfer’s anger as a manifestation of deeper-seated issues related to home, fatherhood, and masculinity—the last of which is in abundance throughout this saga, generally in toxic form.

The Surfer is a character study masquerading as a fantastical schizoid nightmare, and its chaos is scarily amusing—including the fact that Scally eventually resembles an uglier version of Patrick Swayze’s Point Break surfing sage Bodhi.

Cage’s Surfer, however, is no Johnny Utah; rather, he’s a profoundly damaged individual fractured beyond repair by a lifetime of slights, disappointments, and failures. Awash in images of scampering lizards, predatory spiders, and rampant filth—complete with a water fountain rendered useless by a stinking bag of poo—the film operates like a dream that’s so feverish, it’s liable to fry the brain. If its numerous signifiers, motifs, and recurring devices are occasionally wearisome, they’re an apt extension of the Surfer’s unreliable and incensed headspace.

Despite the all-consuming delirium, Cage’s performance never tips into excess. On the contrary, his alternately perplexed, irate, and forlorn turn is simply as heightened as the material itself. With inventive insanity, The Surfer plunges into the dark recesses of its protagonist’s soul. What it finds there is crushing wrath and sorrow—both of which, for Cage’s irreparably broken man, can’t just be washed away by a few magic-hour rides on his trusty surfboard.