“This system, what’s most interesting about it is, you’re interacting with peers, you’re exchanging information with a person down the street.”—Shawn Fanning, Napster co-founder

“If we are going to sell our music on the Internet, in whatever way we so choose, we cannot do that if the guy next door is giving it away for free.”—Lars Ulrich, Metallica drummer

“Fuck Napster!”—Dr. Dre

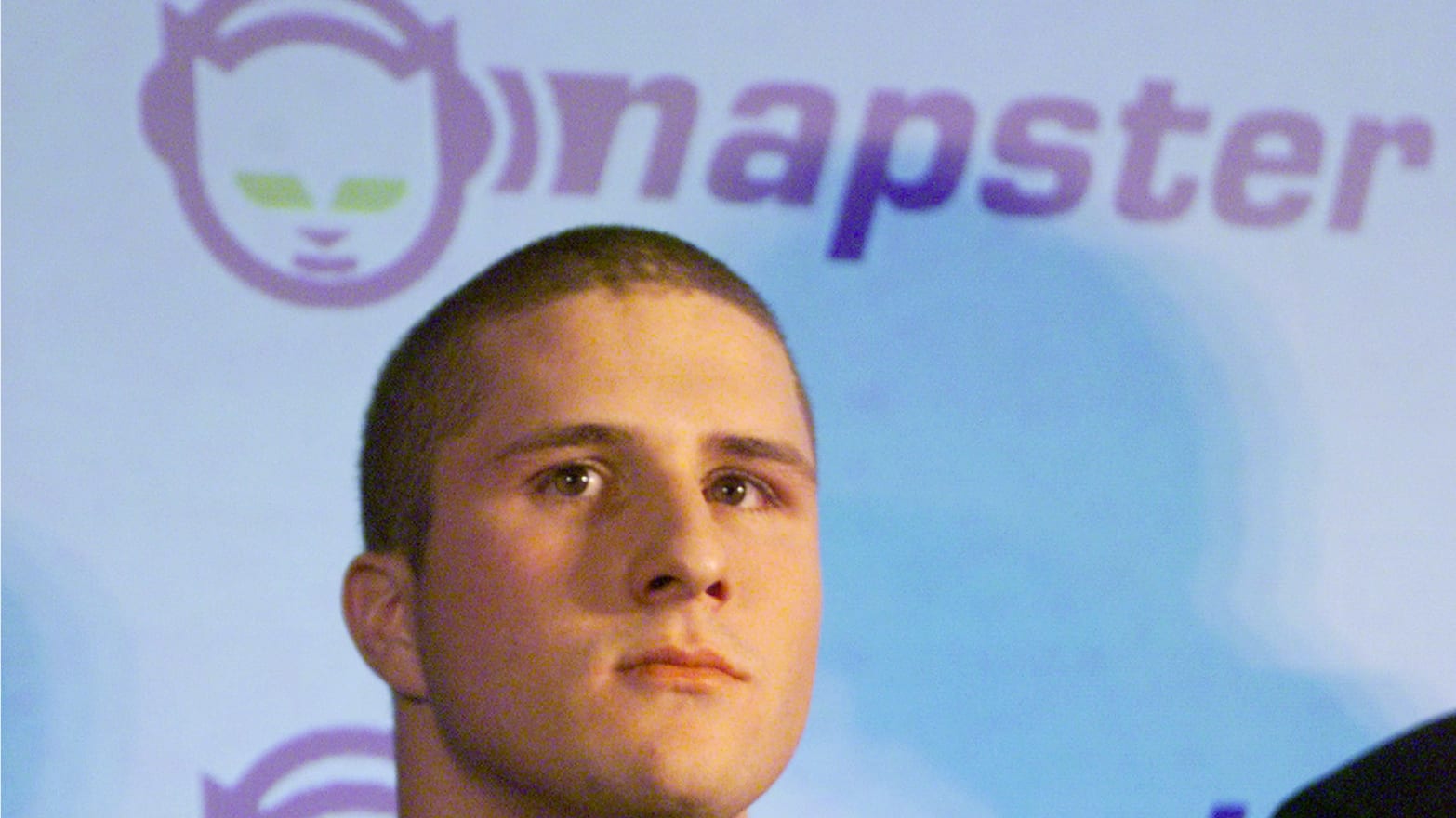

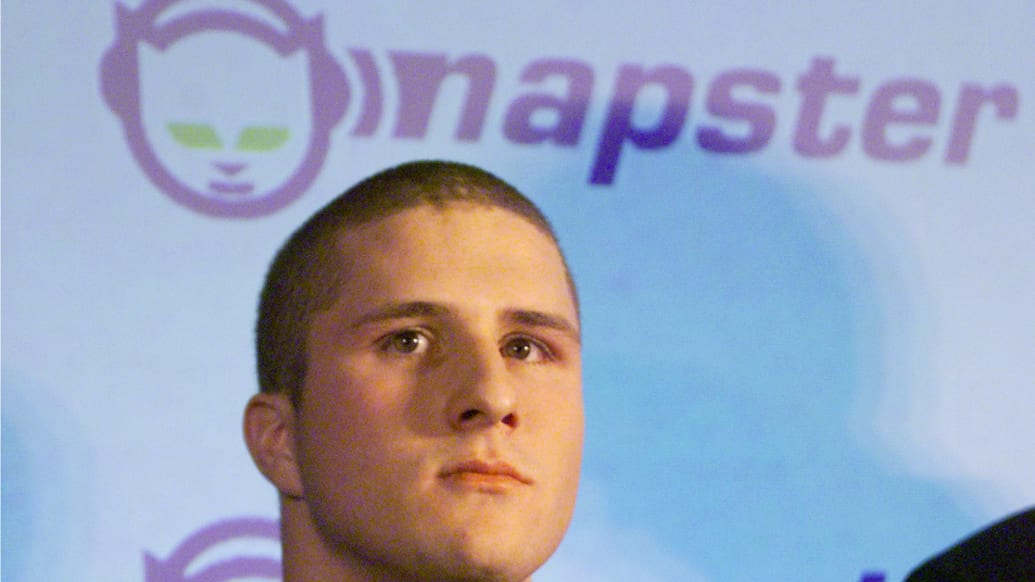

Fifteen years ago, two teenagers revolutionized the way we share and listen to music. At the time, Shawn Fanning and Sean Parker were just amateur developers with a simple idea: an online platform where users could easily swap songs, no strings attached. They called it Napster.

The service, which launched on June 1, 1999, soon spread like a virus, infecting every music nut with a computer and a dial-up connection. By March of 2000, Napster had 20 million users. Several months later, it was more than three times that. By then, the company and its wunderkind creators had been targeted by the RIAA (Recording Industry Association of America) and its suite of attorneys, along with several global superstars like Metallica and Dr. Dre. To the music labels, Fanning and Parker were completely upending a system that had been in place for decades, toying with a carefully crafted mechanism that allowed the artist, the manager, and any middlemen a certain percentage of each record sold. To the musicians, the Napster co-founders were outright thieves, providing an avenue to steal music without paying a dime for it. Depending on what side of the aisle you fell on, if you worked in the industry or if you were just a regular old music fan, Parker and Fanning were either the villains or the heroes.

I was 12 years old when Napster launched, and, at the time, I thought it was the greatest invention in the history of the universe. You mean I can download a prank phone call from a group called the Jerky Boys and that one song by Jamiroquai I don’t know the name of and not have to pay money for it? Sure! For someone unfamiliar with copyright laws and the convoluted maze of the music industry, it was like finding buried treasure over and over again. No longer would my friends and I have to spend most of our allowance just to hear one song on one album, no longer would we have to beg our parents to drive us to Tower Records, no longer would we have to futz with those impossibly difficult stickers attached to the outside of CDs that made you want to throw the entire thing against a wall.

Of course, the dream didn’t last. Due to the RIAA’s lawsuit, Napster ended up shutting down in July 2001, its creators eventually forced to pay millions of dollars to artists and copyright holders. Since then, Napster has gone through several iterations. The service still exists today, however, it’s a hollowed shell of its former self—part of the music subscription service known as Rhapsody.

Hundreds of download programs have come and gone since 1999 (Limewire, Kazaa, BitTorrent, to name a few). Napster deserves credit not just for being the first, but for revolutionizing a new frontier in music consumption. Even today, its legacy and its effect on the industry are still very much in play.

Everyone has their own story about their first encounter with downloaded music. For millions, Napster was the vehicle for that encounter. On the 15th anniversary of its launch, I reached out to a dozen music journalists and editors for their thoughts on Napster——their initial feelings about it, whether they used it, its overall effect on the industry and music listeners, and any other memorable stories they had. This is what they had to say.

Kurt Loder (former MTV News anchor, 1987-2000)

I heard about Napster as soon as it started, and along with many other people was immediately struck by its earth-shaking implications for the big record companies. Now, consumers who had long resented being forced to buy whole albums just to get one or two tracks were empowered to make their own choices. Now there was a way to obtain old music that the record companies had allowed to drift out of print. The service was a major boon for new artists, most of whom had no access to the sort of international promotion in which the gatekeeping major labels specialized; now they could build a career on the enthusiasm of music fans worldwide, freed from the business calculations of the music industry. The social aspect of all this was exciting.

That said, though, I believed then and still do that the appropriation of intellectual property without compensating its creators is theft. I once had an on-air disagreement about this with Chuck D., a smart guy and a sincere Napster advocate…

It’s often noted that that the advent of Napster represented a cultural paradigm shift; and to the extent that it paved the way for legal download services like iTunes (which started the same year that Napster crashed), it was disruptive in a salutary way. However, to the extent that it inaugurated the current era in which many people feel that everything on the Internet should be free for the taking, I think it created moral and monetization problems of which we’ve not yet seen the end.

Steven Hyden (Staff Writer, Grantland)

I remember being excited about it for obvious reasons; it was the first time that seemingly every album you’d ever want to hear was accessible. Or relatively accessible anyway——it could take forever to actually download stuff, and files were always mislabeled. I remember being weirdly excited about downloading Swervedriver’s Eject Seat Reservation, which I couldn’t ever find in a regular store and had only read about previously…

[Now] I think it’s clearly stealing. You can justify it any way you want but it’s still taking something for free that you’re supposed to pay for. But downloading music now almost seems old-timey. A kid born the year Napster came out, I’m sure, would wonder why you would bother storing all that data now that you can just stream music for free on YouTube.

Chris Molanphy (Music critic, contributor to Pitchfork and Slate)

I realize Napster was invented by a college kid who wanted to trade live bootlegs, but my interest, as a pop single fan, was in being able to acquire individual tracks cheaply… While I bought plenty of full-length CDs, it seemed unfair to me that I couldn’t have, say, Eagle-Eye Cherry’s “Save Tonight” without ponying up an Andrew Jackson for a full album. I liked CDs; all I really wanted to do was download the stuff I wasn’t otherwise going to buy on CD. If these songs had been on sale for three or four bucks, I’d have happily bought them.

I don’t remember my first Napster download per se, but I do remember my first, “Oh, wow” download, and it was within the first couple of weeks I was using Napster. It’s not a hip song at all, but it was oddly rare: the extended “Special” mix of Peter Gabriel’s “In Your Eyes.” For years, I’d been scouring record bins looking for the full-length studio (not live) recording of the song, about eight minutes in length, that contains a whole extra intro/verse that Gabriel commonly performs live but which didn’t make the album or any of his greatest-hits albums. I’m pretty sure I started searching for the long “In Your Eyes” immediately after I downloaded a Napster client in 2000, and I couldn’t find it for a week or more…One day I played some more with search terms and finally saw a download with a different, promising title and a much higher file size, and when I clicked to download it at my pitiful Earthlink speed, it took more than an hour. But that was it! The version of the song that I had indeed remembered correctly, wrested from the back of my brain! Several weeks’ searching wasn’t instant gratification, exactly, but considering that this single had been my white whale for more than a decade, I considered that a perfectly reasonable time investment.

Brian Hiatt (Senior Writer, Rolling Stone)

When Napster first appeared, I was covering music news for a website called Sonicnet, and later covered the Napster lawsuits for MTV News. I mainly saw Napster as a great story. As a music fan, it was very exciting to finally have access to something close to a celestial jukebox—all music, instantly. But it also was very disturbing to know they and their labels weren’t getting compensated—I knew that situation could not stand.

The RIAA would have been fools not to have brought that initial lawsuit against Napster. But later, they also may have missed a huge opportunity to settle and turn Napster into a paid service—that could’ve changed the course of the business’ history. The multi-year gap between the death of Napster and the birth of iTunes was extremely damaging for the music industry—too many years went by with few decent legal options to download or stream music.

Chris Richards (Pop music critic, Washington Post)

In 1999, I was a college junior with a lousy computer. My social circle at that time was the D.C. punk scene and we were all listening to vinyl. So when I first heard about Napster, I thought it was something for computer nerds. So much of my worldview at that time was informed by the ethics of the punk scene. So at the time, I thought that music should flow freely and millionaires shouldn’t ever be allowed to complain about anything. By 2003 or so, I finally had the resources to buy a laptop and an iPod. A friend introduced me to Limewire and I was off to the races.

I think the conversation about Napster often focuses on the death blow it dealt to the record business, but too rarely investigates the tremendous impact it had on musicians and their work. I think that impact has been overwhelmingly positive. Napster granted musicians instant access to vast swaths of music in a way that was previously unimaginable. Today’s musician has a much larger vocabulary and Napster certainly has something to do with that.

Dan Reilly (Freelance journalist, former editor of AOL Music’s Spinner)

I thought [Napster] was really cool, but I was definitely a bit wary about the legal ramifications and conflicted about how it affected the smaller artists. I remember being jealous of my friends who were in college with ethernet connections while I had a dial-up connection that took hours to download a single song…

I’d say the invention of the MP3 was more revolutionary, but Napster is the poster child of the traditional music industry’s transformation into what it is now. I think it caused enough debate, reflection, and innovation to create the current state of accessibility, which I love. To blame Napster for all the industry’s ills is a reflection of people’s unwillingness to let go of the status quo and not admit to a lack of foresight of how the digital universe would change music, not to mention other “dying industries” like print news and book publishing. Napster was just one of the first to recognize the Internet’s potential for sharing and people’s love of easy accessibility. Amazon, iTunes, Facebook and more are the ones reaping the benefits of that now.

Lauren Nostro (Music News Editor, Complex)

I was 10 years old and had been using MS-DOS for years on my dad’s laptop…At the time, TRL was huge so you’d run home from school, watch it, and then try to download whatever you heard. Other than that, Napster was the start of downloading a ton of songs and making CD mixes that you’d beg your mom to play in the car. I’d be fronting if I said it wasn’t something that defined the start of my middle school life, and that I don’t remember sitting on the bus bragging about what I downloaded the night before…

For people my age, it always seemed like Napster got sued and then it was on to the next program. It was Napster, it was Limewire, it was Frostwire, and there were all of these programs for people that were my age to actually download music on your own without having your parents drive you to a record store…I was too ignorant to think about how artists didn’t profit. I just wanted all the music at the drop of a hat.

Frannie Kelley (Editor, NPR Music; co-host NPR’s Microphone Check)

I used it a ton when I got to college. I had zero dollars. Buying even used CDs like I had been in high school was not happening. Everybody I knew burned each other mixes constantly. That was how we put each other on, and we got all those songs off Napster. It was mostly classics, too, ’50s and ’60s R&B, older Sizzla and Capleton, because we were trying to educate ourselves…

Albums were more precious to me before Napster. My brother and I got into a physical fight, like rolling on the floor, over Brandy’s first album. I talked him into buying it with his money and then I wanted to tape it right when we got home. Because of Napster, and all the other file-sharing services we used, we stopped punching each other so much. We just listened at the same time. That’s ridiculous but it’s real. The idea that recorded music isn’t something to hoard or protect has made listening to those files more communal. Putting somebody on is the best feeling in the world, and a very rosy interpretation of Napster’s legacy is that the service made that practice more common.

Robin Hilton (Co-host of NPR’s All Songs Considered)

To talk about Napster now feels like a shameful confessional to illicit, youthful activities. Yes, I smoked, but I didn’t inhale! Which is to say, yes, I downloaded some songs, but I didn’t like it. The bit rates were poor, metadata inconsistent or nonexistent. I worried about viruses and hacking. It just wasn’t worth it.

Looking back, Napster was really just an inevitable and necessary step toward getting us where we are today with online stores and streaming services. It forced everyone to take the new century seriously. It wasn’t a sustainable model, but it opened Pandora’s box.

Dan Rys (Senior Editor, XXL)

[Napster] were the little douchebags who didn’t want to play by the rules, who pissed off their parents, and in the process wound up completely changing how an entire generation came to understand music. I think what the real legacy is not necessarily how it supremely fucked the record industry—which it well and truly did, and not in a bad way—but how it changed how the world viewed music. Things at the same time became more decentralized and more focused; more people could get access to more artists and more genres whenever they wanted, and it simultaneously made it more difficult to break into the industry while lowering the bar for the talent level that that entry required. I don’t think you get the Psy’s and the Trinidad Jame$’ of the world without Napster punching that first hole through the wall.

Jessica Hopper (Editor, Pitchfork Review; Band advice columnist, Village Voice)

I did PR for bands in the ’90s, and I remember labels being really frightened, really scared and frantically trying to find a way to stem albums being file-shared—and it was impossible to do so, all efforts were in vain. Some artists were just happy to have their music out [but] the labels were just wringing their hands.

I think the ease of being able to obtain music for free instantly has diminished its value. A lot of musicians write into my Fan Landers column that I do for the Village Voice with questions about if they should even bother charging for music because they know everyone expects to just have it for free.

Carl Wilson (Music Critic, Slate)

The music industry responded [to Napster] with a hysterical-sounding campaign, and then it started criminalizing and suing kids. Which was an idiotic and disastrous choice. It took creators from outside the music industry—from Apple and iTunes—to show the way to a more imaginative response that worked with the technology rather than against it. There’s no percentage in fighting the future, at least not in the entertainment biz.

[Now] it’s less what Napster itself spawned than what it revealed—that we were entering a whole new era in music distribution and consumption. I’ve been sad about the near-death of the record store, and very concerned about artists’ economic lives, but it’s also been a very exciting, dynamic time. The industry losing some of its control has been positive, just as I hoped it would be at the time—the wide-open way music is discovered today has broken down barriers between genres, between the “commercial” and the “artistic,” between audience niches. (As much as I loved them, record stores reinforced all those hierarchies with their genre-based sections and their disapproving clerks.) But as the Napster battle indicated, the primary division is generational, and the (related but not identical) issue of tech literacy, between those who have trouble adjusting to the new way and those for whom it’s second nature. Napster was one of the first big music controversies where the story was about software, not about songs or performers, and that certainly was a harbinger of things to come.