Given Detroit’s current economic state, it’s hard to believe that—in the not-so-distant past—the city was a thriving metropolis filled with industrial fervor, architectural ingenuity, and some of the world’s best art and artists.

But, as 2014 rolled around, Detroit was mired in an unprecedented citywide bankruptcy. The city’s prominent art collection, located in the Detroit Institute of the Arts (DIA), which holds one of the largest and most significant collections in the United States, one that easily rivals that of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, faced the looming possibility of being sold to repay the city’s creditors. As imagined, the art world was up in arms.

Luckily, a “grand bargain” was signed on June 5 in which state lawmakers unanimously approved a transfer of all city-owned art to a charitable trust, keeping the works safe, and safely in Detroit. The timing couldn’t have been more perfect for the Detroit-born director of Levin Art Group, Todd Levin.

His most recent exhibition, Another Look at Detroit, opened last Thursday in New York City. “This is not an exhibition about geopolitics or macroeconomics or global finance. This is not an exhibition glorifying the misguided aesthetics of destruction porn,” Levin described in the show’s press release. “It is neither a feel-good exhibition trying to accentuate the positive, nor an attempt at organizing a proper historical overview of how a city was birthed and decayed.”

Instead, the two-part exhibition, which takes place at the Marlborough Chelsea and Marianne Boesky galleries in Manhattan’s Chelsea neighborhood, is Levin’s return home, bringing together roughly 100 works by some 70 artists from the past two centuries.

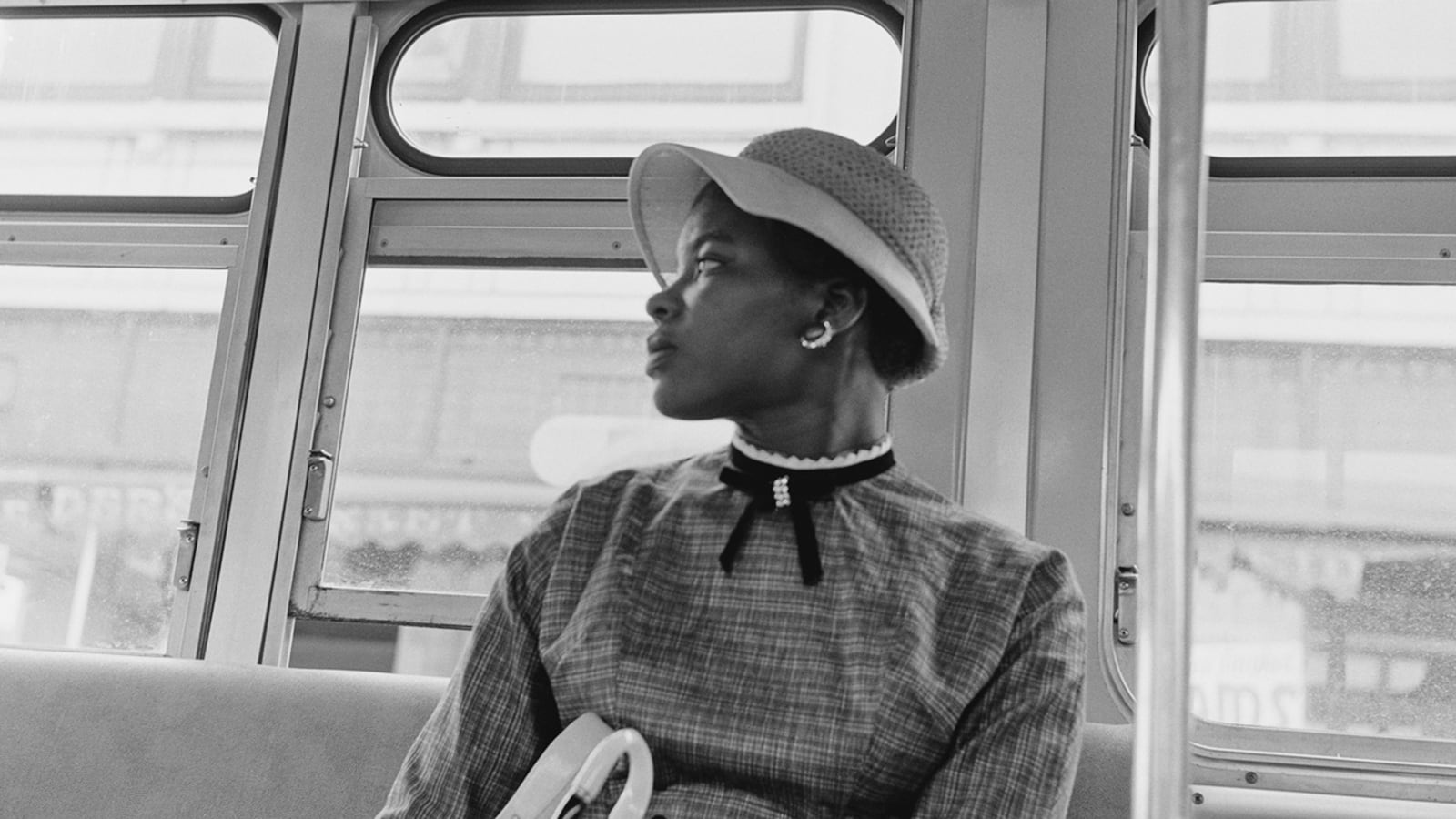

From photography to painting and automobilia to fashion, Levin includes all types of artistic creation by those who were raised in, moved to, or have been inherently inspired by the Motor City.

Detroit native Mike Kelley, for instance, is one of the most influential and well-known contemporary artists of his time. In 1975, he moved to Los Angeles at the age of 22, but his work—from massive stuffed-animal sculptures to performance art and sound installations—continued to reflect his formative years spent in the city.

Kelly’s “Center plus peripheries #2” features a blank canvas with five black-and-white images orbiting its outer border: two men, a garbage bag, a thumb, and—in homage to childhood—a cartoon-like character.

Diego Rivera, on the other hand, spent only a brief part of his life in Detroit after he was commissioned to create iconic murals throughout the city, yet his presence is undeniably entwined in the city’s historical development as a thriving metropolis.

His portrait of Henry Ford’s son, Edsel B. Ford, hangs in the Marianne Boesky gallery. Rivera depicts the automotive heir, known for his successful contributions to the advancement of Ford’s automotive designs, standing among sketches and various drafting tools.

The DIA and the Cranbrook Museum of Art, along with the Detroit Historical Society and Ford Motor Company, have all donated works for the exhibition. Ford, which was founded in Detroit in 1903 and introduced the first affordable automobile to the United States, loaned a large portion of the works, providing advertisement, catalogs, and fabric sample books from its historical archives.

“Because of the amount of money that the automobile industry generated,” Levin told The Daily Beast, “particularly between the Great Depression and 1960, [Detroit] built a museum that is now probably one of the top 10 in the country.” The Detroit Institute of Art was built in 1927 and has a collection valued at more than 1 billion dollars. The Ford Motor Company is also one of three major automobile manufactures donating a combined $26 million to the DIA to help protect the city’s renowned art collection.

“The D.I.A. and the city of Detroit need our help,” Ford’s executive vice president, Joseph R. Hinrichs, said at a recent press conference. “And we are here, as we’ve always been, to do our part.”

The dual gallery exhibition includes a suit from Detroit-born designer Anna Sui’s debut fall collection from 1991 as well as furniture crafted by powerhouse designers Charles and Ray Eames and Eero Saarinen.

In addition to big-name artists, Levin also went on various studio visits with up-and-coming creators whom he had never met, such as Danish artist Marie T. Hermann, who moved to Detroit when her husband accepted a position at the Cranbrook Academy—another institution who loaned very generously. Hemann’s work blends Old World craft with contemporary art, which seemed peculiar to Levin until he saw it in person. “When we did the studio visit I was just really blown away by her personally, intellectually and the work itself.”

Bringing together past and present artists across a wide range of fields, Another Look at Detroit captures the creative essence of a city knocked from its pedestal. Whether or not the art has the power to redeem the city’s fall from grace, it certainly transforms an outsider’s view of Detroit from one of ruins to a place of thriving creativity.

Another Look at Detroit is on display at the Marlborough Chelsea and Marianne Boesky galleries in New York City until August 8, 2014.