HONG KONG—In China, even the pigs are under surveillance.

There’s good reason for that. The country’s hog-raising industry is cleaning up the pigsty, with companies like Alibaba, JD, and NetEase—all major technology companies that shape how Chinese citizens interact with the internet—developing systems to monitor hogs and sows using facial recognition technology.

Artificial intelligence determines how fast each pig is growing and whether it is healthy. Automated systems interpret that data to adjust environmental controls and feed rations. In some cases, sound sensors pick up coughs, and raise flags about potential sickness for the farms’ operators. Blockchain tech is used to keep track of each pig from birth, through growth, to slaughter, and finally in retail.

This all sounds a bit bizarre and more than a little sinister. (If one were rewriting George Orwell’s Animal Farm today, facial recognition technology could play a part determining which animals are “more equal than others.”) But for now the goal is simple: to create accountability.

Food inspectors do what they can to seize dubious meat, but some shipments still make their way into supermarkets all over China, as African swine fever has swept through the country, wiping out millions of pigs.

China is the country that breeds and consumes the most pigs on Earth—half of the world’s stock is raised in the country. The People’s Republic even has a strategic reserve of frozen pork that is estimated to be about 200,000 tons. In all, China’s pork industry is a $128 billion business annually.

At present, the virus has been found in all of China’s provinces, devastating pig stocks across the country. African swine fever does not affect humans, but is deadly to hogs, approaching a 100 percent fatality rate. It has a long dormant period and is highly transmittable, and there have been cases where an envelope that passed through the postal service carried the virus and infected live pigs near its recipient. Already, Chinese tourists carrying sausages have brought African swine fever to Taiwan, Japan, Thailand, and Australia.

Some years ago, this writer worked in a factory located in Southern China. It was located two lots away from a slaughterhouse that butchered truckloads of pigs each day. Every evening, after most of the workers in the industrial park had returned to their homes or dorms, the slaughterhouse would discharge a torrent of blood, guts, and filth into a nearby water channel. Complaints to the local government apparently went nowhere. Abuses like these, which can still be found in China, make it impossible to halt the infections. Some farmers have resorted to burying pigs alive to save their stocks.

There is no vaccine for the disease. Last month, Dutch financial services firm Rabobank estimated that up to 200 million pigs in China could be culled or die from sickness because of African swine fever in 2019. Last month, the United States Department of Agriculture projected that China would lose 134 million pigs, just about what the U.S. exports each year.

What many of those pigs have been used to eating is meal made from American soybeans. But, to state the obvious, dead pigs don’t eat, and those many bushels of soybeans that were not shipped from the States to China—a 97 percent drop last year—may be more about febrile swine than the U.S.-China trade war. It certainly means the way Washington and Wall Street use soybeans as a barometer for the ferocity of the economic feud is misplaced, not that there is any consolation for the American farmer.

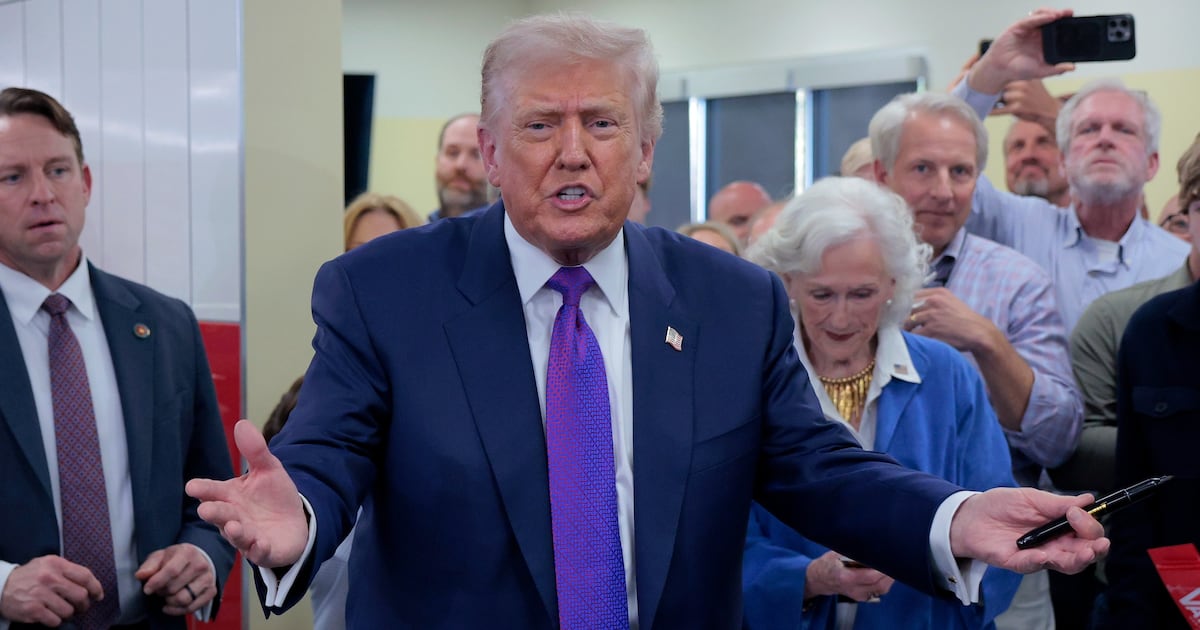

Is it at all surprising that Donald Trump failed to see the entire board?

Earlier this month, Trump bumped up tariffs on $200 billion worth of Chinese goods, taking the rate from 10 percent to 25 percent. Telecommunications equipment is the top category with $19.1 billion of goods at stake. This has prompting Beijing to say it would take “necessary countermeasures,” though details, as with many of the trade war’s other episodes, are nonexistent.

The dispute by tweet and tariff between the world’s two largest economies has made individuals and businesses on both sides of the Pacific uneasy, even leaving them at a loss. America’s soybean output aside, there’s actual risk that Trump’s strategy—or lack thereof—will tilt the U.S. into recession by 2020. It’s a conclusion drawn by researchers at UCLA, 42 percent of business economists polled by the National Association for Business Economics, two-thirds of CFOs who responded to a survey by the Duke CFO Global Business Outlook, and more.

The winds in Beijing have shifted. In the past few weeks, Xi Jinping has become harsher, less patient with Trump’s flippant, delirious, hog-wild attitude toward negotiations.

With no deal in sight, folks in China are comparing Chinese Communist Party Vice Premier Liu He, who was in Washington for talks, to a 19th-century official who signed away chunks of the Chinese Empire to foreign powers. It’s a damning proposition, one that can’t sit well with the Party’s higher-ups.

Trump may want the fight to drag on so he can replay the tune of “American First” ahead of the 2020 presidential election, but across the Pacific, Xi needs a win fast. October 2019 will mark the 70th anniversary of the CCP coming to power in China. Any outcome besides a proclamation that the Party has weathered Trump’s tariff-obsessed tweetstorms simply won’t stand.

Before swine fever hit, China was near peak pork, but there will be shortages this year, perhaps up to 30 percent. Already, the Chinese are switching to a different red meat—beef. But it isn’t coming from Texas, Nebraska, Kansas, or any other state with cattle ranches. Mostly it’s coming from Australia and Brazil. Xi has slapped tariffs on American beef in response to Trump’s measures, ones that will leave Americans hurting, too.