Earlier this year, Netflix’s The Confession Tapes recounted, via six real-life cases, the ways in which false confessions might be elicited by law enforcement. But what if an untrue admission wasn’t the byproduct of coercion, or a suspect’s lack of education, or the terrible pressure of a given circumstance, but the result of maniacal love?

That’s the argument forwarded by Killing for Love, Karin Steinberger and Marcus Vetter’s riveting new documentary, whose two-hour theatrical version (debuting Friday, Dec. 15 in NY and LA) has been assembled from a larger six-part TV series that aired earlier this year on the BBC.

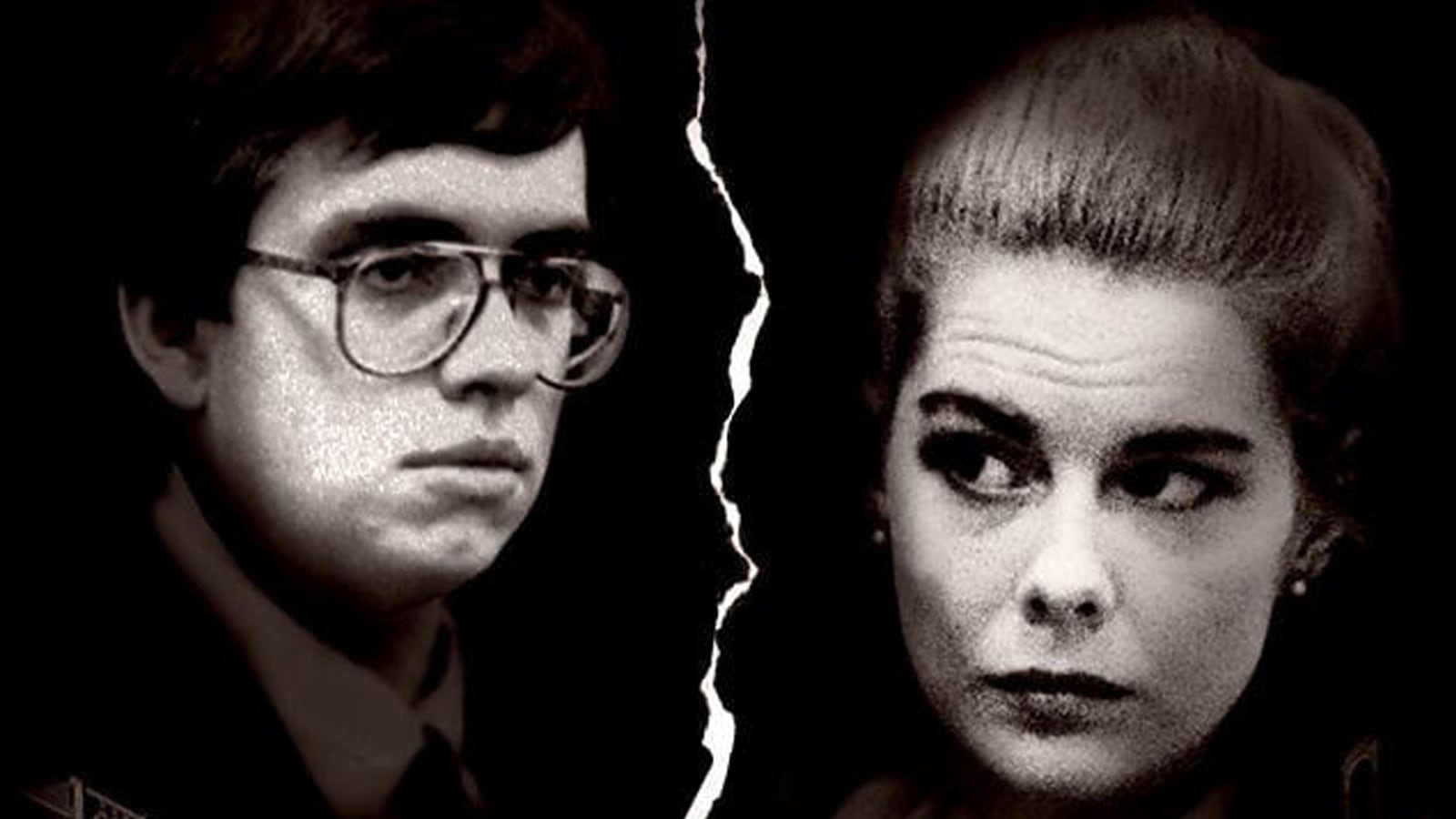

Steinberger and Vetter’s subject is the double homicide of Derek and Nancy Haysom, a well-to-do couple who, on March 30, 1985, were found viciously stabbed to death in their Bedford County, Virginia, home. The initial prime suspects were the Haysom’s college-aged daughter Elizabeth (a Canadian citizen) and her younger 18-year-old University of Virginia boyfriend Jens Soering (the son of a German diplomat). Those two soon fled the country, passing fake checks to survive until they were arrested and sent back to the U.S., where Elizabeth was sentenced to life in prison in 1987 for helping orchestrate the slaughter, and Jens—in what would become the first nationally broadcast trial ever from Virginia—was convicted of murder in 1990 and locked up for life.

On the face of it, it was an open-and-shut case: two lovers conspiring to commit a heinous atrocity, and then doing their best to cover their tracks and evade capture. But beneath the surface, their saga was anything but simple, as Killing for Love makes clear.

The film begins with footage from Elizabeth’s guilty plea hearing on Oct. 6, 1987, during which she admits that she used to refer to herself as “Lady Macbeth,” whom prosecutors helpfully point out for the court was a character who convinced her husband to slay the king. Then, she’s asked if she was sexually abused by her mother, who was rumored to have taken a series of nude photos of Elizabeth and then exhibited them for her friends. Shortly thereafter, the directors cut to Jens, now a middle-aged man in prison, sitting down for an interview. “I have destroyed my life,“ he says. “Because I thought it was about love. But this love didn’t exist.”

Thus Killing for Love embarks on an investigation into the real reasons for the Haysom’s deaths, which—as implied by the song bookending the film, “I Put a Spell On You”—had mostly to do with a daughter’s fury and a man’s susceptibility to her romantic charms. Elizabeth, as it turned out, was a drug addict and one-time runaway; a beautiful and charismatic “wild” woman who attracted (and reciprocated) the affections of both genders, and whose worldly aura and considerable intellect immediately wowed the impressionable goody-two-shoes Jens.

To be in her orbit was, for Jens (a Jefferson Scholarship-awarded nerd in giant glasses), pure bliss, and after three months together, Elizabeth’s parents were butchered. Elizabeth and Jens had an alibi: they’d rented a car and been in Washington D.C. together, and had in fact purchased movie tickets the evening of the homicide. Then, a few months later, they suddenly absconded to England, where they penned florid letters to each other—which included Jens’ Nazi-guard sexual fantasy, in which he writes that getting over their “nasty” business will be difficult, but Elizabeth will succeed in that endeavor “because you want a good strong fuck and a two-hour licking from the guy who loves you.”

When their overseas check-fraud scheme landed them in prison, Jens confessed to the crime, whose audio recording—like the trial footage itself—is presented in detail by Killing for Love. However, that was only the beginning of Jens’ story, since by the time he was extradited to Virginia to face prosecution, his version of events had changed. Now, he claimed, Elizabeth had massacred her parents, after driving back from D.C. with a heretofore-unmentioned drug-dealer friend named Jim Farmer. Moreover, he stated that he’d owned up to the deed as a means of saving her from the electric chair—the thinking being that, as a diplomat’s son, he’d be found guilty, be imprisoned for a couple of years in Germany, and then be freed, at which point the couple could resume their affair. It was a dumb teenager’s plot, he says, inspired by Romeo and Juliet (since his “motive” was that Elizabeth’s parents didn’t want her seeing him), A Tale of Two Cities and Macbeth. A literary-style fantasy “based on Shakespeare,” the adult Jens admits, shaking his head in disbelieving self-disgust.

Whether Jens murdered the Haysoms himself, or whether Elizabeth did it and he covered for her out of fanatical obsession, is a question that Killing for Love can’t definitely ascertain, given that this tale is one marked by all sorts of loose ends, including: an FBI profile that one investigator says was conducted and another says didn’t happen, and remains missing; the role played by Jim Farmer, who died before a private investigator could track him down; a presiding judge who was a long-time friend of Nancy Haysom; and a garage owner who maintains (much to one investigator’s dismissal) that he helped clean Elizabeth’s bloody rental car, which was supposedly dropped off at his establishment by Elizabeth and another classmate named Ned. Then, there’s the issue of physical evidence, which—even after subsequent DNA tests—put Elizabeth and two other unidentified individuals, but not Jens, at the scene of the crime, save for a bloody footprint that helped seal Jens’ conviction.

The documentary’s habit of seguing abruptly from one focal point to another often feels like the byproduct of it being an abridged form of a much longer TV work. Nonetheless, even if it sometimes feels less graceful and lucid than one might like, and its non-fiction template is a familiar blend of interviews, archival clips, and chilling old photos and missives—some of which are narrated by actors Daniel Bruhl (as Jens) and Imogen Poots (as Elizabeth)—Steinberger and Vetter create a haunting atmosphere of mania and madness, as when they transition to photos of Derek and Nancy during Elizabeth’s cold, eerie testimony.

Like so many likeminded true-crime efforts, the truth is elusive in Killing for Love, and what remains is a lurid morass from which only ugly answers about human nature can be gleaned.