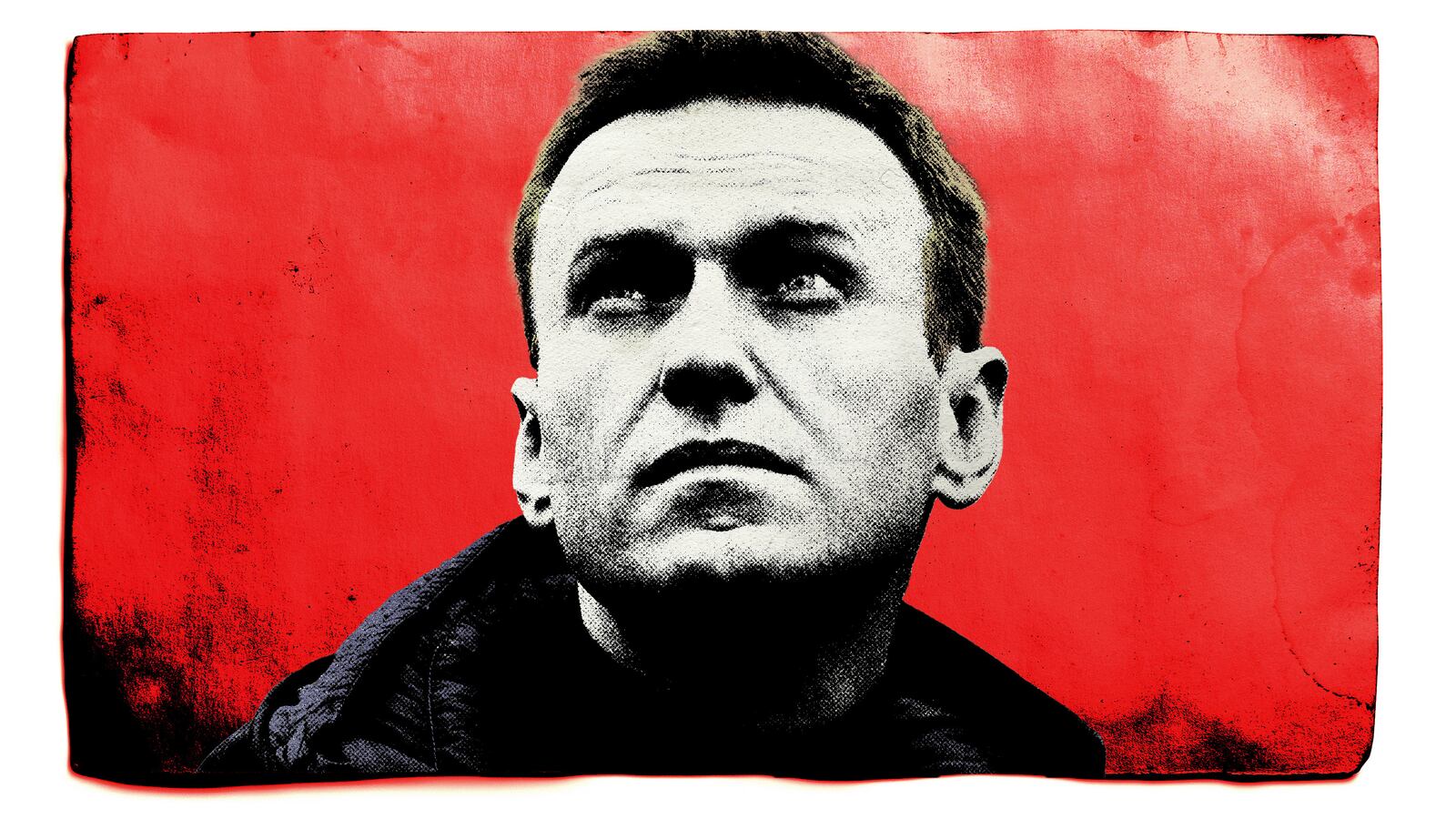

He didn’t have to go. In August 2020, Russian dissident Alexei Navalny had been poisoned, probably at the direction of Russian President Vladimir Putin, who saw in Navalny one of the vanishingly few legitimate threats to his reign.

Navalny went to Germany to recuperate. While there, he managed to confirm that the poisoning had been carried out by Russian security services by calling one of his would-be executioners and pretending to be a fellow Kremlin goon. Mother Russia wanted one of her own sons dead.

So why return? “It was never a question of whether to return or not,” he wrote in a social media post in Jan. 2021. Several days later, he landed at Moscow’s Vnukovo Airport, where he was greeted by admirers.

We Russians in the West admired him, too. I saw in his return a refutation of the argument that all Russians wanted was Louis Vuitton boutiques—freedom and democracy be damned. He came back to remind us, whether we were in Brooklyn or Kaliningrad, that we were better than that. Or that we could be, in any case.

Navalny was promptly arrested on entirely fictitious fraud charges that were intended to keep him sitting comfortably at some Washington or Berlin think tank, no threat at all to the Stalinist project underway in Moscow.

He wasn’t supposed to come back. Only he didn’t get the message.

He would never see freedom again. An obeisant court found him guilty, then tacked on “extremism” charges for good measure. “They really do initiate a new criminal case against me every three months. Rarely does an inmate confined to a solitary cell for over a year have such a vibrant social and political existence,” he said in a typically sarcastic social media post conveyed via his representatives.

Navalny became a cause célèbre, one of the few figures within Russia we Russians could be proud of. In arguing that we were better than the country shelling Ukrainian innocents, we could always point to Navalny, even as he looked increasingly gaunt in the video footage made available by his jailers.

There, look at him. As long as Navalny lives, there is a hope of a better Russia. As long as he lives.

Alexei Navalny speaks with journalists in Moscow, July 20, 2019.

Maxim Zmeyev/Maxim Zmeyev/GettyFinally, they did what so many of us always feared they were going to do. On Friday, Navalny died at the IK-3 penal colony in Kharp, a remote Siberian village. He apparently collapsed after a walk. He had been in poor health for many months, as he moved from one penal colony to another, suffering prolonged stretches of isolation and other privations.

I grew up in the same country as Navalny: the faded Soviet Union of the 1980s. The desperation of those years, and the chaos of the 1990s, drove many Russians (including my own family) to the West. Some of those who stayed only did so because they figured they could get rich. A seller of blue jeans could suddenly become a copper magnate, as long as he could survive the mafia hits that came with a regular cadence in Moscow and St. Petersburg throughout the go-go Yeltsin years.

An attorney by training, Navalny did not stay to get rich. He stayed for the same reason that would see him return in 2021. He truly believed in Russia, in the possibility of a democratic nation rising from the ruins of the Soviet empire.

Alexei Navalny appears via a video link from his prison colony during his appeal against the nine-year prison sentence he was handed in March, in Moscow on May 17, 2022."

Kirill Kudryavtsev/AFP/GettyOnly that wasn’t the country that took shape. “I can’t stop myself from fiercely, wildly hating those who sold, pissed away, and squandered the historical chance that our country had in the early 1990s,” he would later say.

Having never won an election, Putin emerged in 1999 to replace the inept and inebriated Yeltsin. He quickly arrogated every means of power, even as Western leaders like George W. Bush foolishly insisted that he was committed to democracy.

I returned to Russia for the first time in more than two decades in 2003. The country looked almost Western: Western-ish. I was impressed. The erosion of democracy, already underway, seemed like a small price to pay for upscale beer gardens where once had stood drab cafeterias.

Then the price rose. In 2006, the investigative journalist Anna Politkovskaya was murdered for reporting on the brutality of Putin’s campaign to pacify the restive republic of Chechnya, as well as his repressions targeting every segment of Russian society. Politkovskaya saw clearly what was happening. “Who can say,” she wondered, “we are not returning to Stalinist ways under Putin?”

Navalny refused to let it pass.

If some in the West had had a too sunny view of Russia, as if it were nothing but a Harvard Business School case study in unfettered capitalism, there were others who grumbled that Russians were “incapable” of democracy, that something in the Russian spirit required iron-fisted leadership. But whether you believed in the market or the czar, both of these views deprived Russians of dignity and self-determination. We were always to be subject to greater forces wielded by larger-than-life figures, whether Mickey Mouse or Vladimir Putin. It was never our call.

Disenchanted by the cowardice of most Russians with any cultural or political influence, Navalny had, by the end of Putin’s first decade in power, become a full-blown dissident. He started blogging in 2008, then moved towards pure political agitation. It was a dangerous occupation: like Politkovskaya, most critics of the regime were murdered or, if they were lucky, chased out of Russia. “He’s taunting really big people and he’s doing it in an open way and showing them that he’s not afraid. In this country, people like that get crushed,” one Russian official worried to The New Yorker in March 2011.

Alexei Navalny is escorted out of a police station on Jan. 18, 2021, in Khimki, outside Moscow, following a court ruling that ordered him jailed for 30 days.

Alexander Nemenov/GettyIn Dec. 2011, Navalny was arrested for calling into question the results of a sham parliamentary election. The West took increasing notice. The New York Times pointed to his “Nordic good looks” and “serene confidence,” observing that what “attracts people to Mr. Navalny is not ideology, but the confident challenge he mounts to the system.” He went to jail for the first time, for 15 days.

An authoritarian system always knows how to shore up its weakness. After a brief interregnum during which Dmitry Medvedev pretended to play the role of president, Putin returned to power seemingly determined to never cede it again. Since the 2012 election, he has sat unchallenged in the Kremlin. It is widely assumed that he will remain there until death.

Navalny was virtually alone in trying seriously to dislodge him, challenging Putin for the presidency in 2018 only to see his bid disqualified on invented legalities. “The process in which we are called to participate is not a real election,” he said.

By this point, many of us Russians in the diaspora had come to realize that no number of Moscow skyscrapers could disguise the fact that Putin had turned Russia into a gaudy embarrassment, a country that ran on petroleum and propaganda and aligned itself with Syria and Iran. The invasion of Ukraine shattered all remaining illusions.

It was to this Russia that Navalny returned. Soviet history is rich with artists, intellectuals, and scientists who refused to stay silent in the face of state-sanctioned atrocities. Anyone who grew up in the Soviet Union knows their names: Akhmatova, Sakharov, Sharansky. Navalny reminded us of this tradition, of the eternal need to rouse the people of this huge, complicated country, whose day-to-day lives can be so grindingly difficult that it is hard to think of anything but survival.

Navalny believed in ordinary Russians, in their desire for something more than the material comforts bought by Putin’s petrodollars. That is what he came back to. That is what he died for.

Today, a Russia free of Putin and Putinism seems almost impossible to imagine. But for the sake of Navalny, we must imagine it.

“My greatest hope for Russia is that dictatorships always appear solid until suddenly they aren’t,” Uriel Epshtein, chief executive of the Renew Democracy Initiative—who traveled frequently as a child to his family’s native Russia—told me. “Putin may feel untouchable today, but he can still be proven wrong. At a certain point, some part of Russian society will decide that they can no longer live under his yoke.”