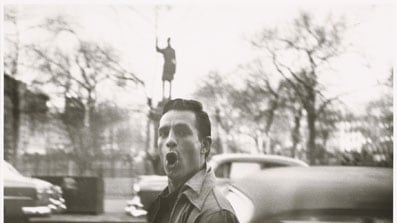

Allen Ginsberg, the Beat poet and bearded Buddhist provocateur of the American status quo, relished the rock-star notoriety and media ubiquity that gave him mythic status in his lifetime. First and foremost, though, he was a poet, and his place in the pantheon of arts and letters remains firmly intact. Still, the poet had a second life as a photographer, and Beat Memories: The Photographs of Allen Ginsberg, an exhibition of 80 photographs now on view at The National Gallery of Art, through September 6, makes a convincing case that his pictures, combined with his handwritten captions, have a poetry of their own.

Click Image to View Our Gallery of Allen Ginsberg's Beat Memories

“Ordinary mind” was one of the phrases Ginsberg used to discuss consciousness in context of his own writing, and, in a 1988 lecture on “Snapshot Poetics” at the Fogg Art Museum, he applied the term to his approach to photography, as well: “Ordinary mind includes eternal perceptions. Notice what you notice. Observe what’s vivid. Catch yourself thinking. Vividness is self-selecting. And remember the future.”

We are the future Ginsberg had in mind and it is our good fortune to be able to view the poet’s matter-of-fact and spontaneous “snapshots” of his small circle of friends—William Burroughs, Neal Cassady, Gregory Corso, and Jack Kerouac—whose camaraderie was culture-changing and settled long ago into the realm of literary legend. Ginsberg’s “ordinary mind” documentation of these towering figures at intimate moments in their daily activities in the 1950s is an unselfconscious and authentic glimpse of these young men before they became “Beat Generation” heroes.

Ginsberg didn’t take these pictures with artistic intentions. They were made in the context of whatever he and his friends were doing at any given moment, never in a forced or artificial manner, whether talking together, staring off into space, or walking around in the neighborhood. He thought of the images as nothing more than keepsakes that recorded “certain moments in eternity,” which he showed to his friends, stored away in a file, and forgot about for many years.

In the late 1960s he placed all his papers in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Columbia University, but it wasn’t until 1983, when he hired Bill Morgan, an archivist, to organize the papers that the old snapshots were rediscovered and brought to Ginsberg’s attention.

Aware that the pictures had historic resonance, Ginsberg called Robert Frank, a friend from the old days when Jack Kerouac had first introduced them in the 1950s, and this “kindly teacher,” as Ginsberg would later describe Frank, gave him very specific suggestions about printing and cropping. Frank referred Ginsberg to several of his own printers, who made photographic prints from his old dime store negatives.

These pictures of famous writers might have remained ordinary snapshots of extraordinary people if it were not Ginsberg’s recognition that “the poignancy of photography comes from looking back to a fleeting moment in a floating world.” He recalled looking at these pictures from a distance of 30 years and asking himself: “What would I want to know if I were looking at a picture of Rimbaud and Verlaine together? What were they doing that day? What had they been talking about? What were they occupied with? Where was it?”

Ginsberg chose to write on each print his reflections about the actual moment captured along with factual details that include the names of the subjects, the place, and the date. In so doing, he extended the images beyond the picture frame. They grew from snapshots to photographic prints and, then, to meditations that are as much visual record as written memory.

Ginsberg did not photograph those moments because they were poetic; he made them poetic because he photographed them, and, then, recalled what was happening as a witness from the future looking back through layers of personal experience and cultural history. As Sarah Greenough, Senior Curator of Photography at the National Gallery, writes in the exhibition catalog: “Recognizing that much of the power of photography comes from looking back to a long gone moment in time, Ginsberg made the collision between past and present the subject of many of his captions.”

In one picture, William Burroughs and Jack Kerouac are sitting on a couch. Burroughs’ expression is both patronizing and playful. Ginsberg’s caption reads: “‘Now Jack as I warned you far back as 1945, if you keep going home to live with your ‘Memere’ you’ll find yourself wound tighter and tighter in her apron strings till you’re an old man and can’t escape....’ William Seward Burroughs camping as an Andre-Gide-ian sophisticate lecturing the earnest Tom Wolfean all-American youth Jack Kerouac who listens soberly deadpan to ‘the most intelligent man in America’ for a funny second’s charade in my living room 206 East 7th Street Apt 16, Manhattan. One evening Fall 1953.”

Ginsberg wrote the caption knowing all that had since transpired since the picture was taken—Kerouac’s great promise in 1953, his attachment to his mother, his alcoholism, his sad decline, and his death at the age of 47 in 1969. Ginsberg gave to Burroughs the dialogue of a wry sage, fully aware of the position history had since assigned both men. The caption reflects the poet’s affection for his subjects and, also, his conclusions about them—a revealing bit of oral history that matches the visual moment.

In lectures, Ginsberg would refer to the Imagist poets. “They specialized in brief poems, flashes of the moment, visual poems,” he said, that were like “little descriptive photographic worlds, almost cinematic in nature.”

Ginsberg recalled that the poet William Carlos Williams, one of his own mentors, was a friend of the photographer/painter Charles Sheeler and, also, Alfred Stieglitz. “So there has always been some correlation between photographers and poets since the 1920s.”

Still, Ginsberg, by writing on his own photographs, took his cue as a poet who had learned early lessons from his friends, the Beats. Kerouac had described using language largely based on the act of sketching and he had advised Ginsberg and Burroughs “not to begin from a preconceived idea of what to say about an image, but from its 'jewel center' of interest at the ‘moment of writing.’ " Capture the segment of time, he wrote, “everything that is happening in front of you, [for] there is your perfect poem.”

While the glamour that history has bestowed upon the poet and his subjects may be the most conspicuous attribute of these photographs, Ginsberg used each one as a ‘jewel center of interest’ for the ‘moment of writing’ his captions. Without question, the combination of visual moment with written memory reaches to the core of “Beat, Buddhist poetics” itself. Ginsberg’s pictures strike a balance between being here now and being here then—a zen koan, if ever there were one.

Plus: Check out Art Beast, for galleries, interviews with artists, and photos from the hottest parties.

Philip Gefter writes about photography for The Daily Beast. He previously wrote about the subject for The New York Times. His book of essays, Photography After Frank, was recently published by Aperture. He is currently producing a feature-length documentary on Bill Cunningham of the Times, and working on a biography of Sam Wagstaff.