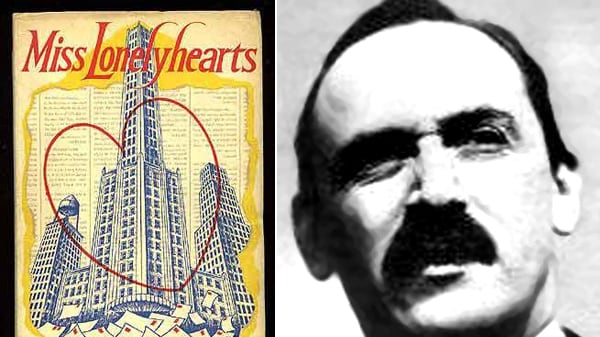

Herbert Hoover used the word “Depression” to describe the nation’s financial miseries advisedly. He felt it would cause less alarm than “crisis” or “panic,” terms that were more commonly used at the time to describe financial collapse. But Hoover’s nomenclature was a self-fulfilling prophecy. Panics and crises, painful as they might be, tend to resolve themselves quickly. The Great Depression caused great depression, the incineration of the stock market cauterizing the national mood, yielding a period of cynicism, inanition, and despair. No novel captured the spirit of this time more indelibly than Nathanael West’s Miss Lonelyhearts, which was published in the year that the national unemployment rate reached its highest level. Twenty-five percent of American workers were unemployed in the winter of 1933, but one job remained in high demand: newspaper advice columnist. The misery industry was booming.

The idea for the novel arose from a dinner that West had with the writer S.J. Perelman, who was his brother-in-law, and Quentin Reynolds, a former college roommate of Perelman’s. Reynolds wrote an agony column, “Susan Chester Heart-to-Heart Letters,” for the Brooklyn Eagle. He thought that the pathetic letters he received might be of use to Perelman for one of his humor pieces, but Perelman found the letters too depressing to be mined for comedy. West, on the other hand, immediately understood their potential. He stuck them in his pocket, and would later copy them, almost verbatim, into his novel.

It’s ironic then that the most comical moments in Miss Lonelyhearts come from these letters, whose authors sign their names “Desperate,” “Disillusion-with-tubercular husband,” “Broken-hearted,” and “Sick-of-It-All.” But the humor is black, disturbed, curdled:

“I have a big hole in the middle of my face that scares people even myself so I cant blame the boys for not wanting to take me out.”

“Gracie is deaf and dumb and biger than me but not very smart on account of being deaf and dumb.”

“…I always said the papers is crap but I figured maybe you no something about it because you have read a lot of books and I never even finished high.”

West’s columnist, who is only identified as Miss Lonelyhearts, laughs at these letters himself, but not for long. “He could not go on finding the same joke funny thirty times a day for months on end,” writes West. The joke, Miss Lonelyhearts soon realizes, is on him.

The letter writers ask for help and wisdom, but all of their pleas can be reduced to a single question—the big question. It is posed most memorably by a cripple named Peter Doyle, who works merciless hours only to come home to a cruel, unfaithful wife. “What I want to no,” writes the semi-literate Doyle, “is what is the whole stinking business for.”

West examines all of the conventional answers, holding each up to scrutiny, before discarding them with disgust. A life devoted to pleasure; to art; to a self-sustaining agrarian existence; to exotic travel; to drugs—all are revealed to be foolish fantasies, one more ridiculous than the next. Happiness is a fraud, a sickness even. Life is the sum of suffering and tawdry pleasures. Man is a stupid, greedy animal. Depression is not only the spirit of the time—it is the eternal human condition. Even suicide is deemed absurd. West reserves the greatest disdain, however, for the consolations of religion. “If he could only believe in Christ,” he writes, “then everything would be simple and the letters extremely easy to answer.” Elsewhere he writes: “Christ was the answer, but, if he did not want to get sick, he had to stay away from the Christ business.”

But Miss Lonelyhearts can never escape the Christ business, no matter how much he and his colleagues ridicule religion and its devotees. This is why the novel’s ending, in which Miss Lonelyhearts becomes a Christ figure himself, has puzzled readers for eight decades. What to make of his transformation from cynic to martyr? It seems impossible that he has found religion. But equally impossible is the idea that he has become a secular Christ who finds redemption in comforting others. Most likely, it seems, is that, after a terrible fever that keeps him in bed for three days, Miss Lonelyhearts has gone insane. This is the gloomiest interpretation of all—that life, and suffering, have no meaning whatsoever.

The novel’s power lies in its sick laughter in the face of implacable doom. No act of charity goes unpunished. When Miss Lonelyhearts forces himself to take the hand of the cripple Doyle in a gesture of compassion, he must resist his revulsion. Sex is no less grotesque; during the act he hears “the wave-against-a-wharf smack of rubber on flesh.” Even a vacation with his fiancée to an idyllic Connecticut farm turns into a nightmare: “Although spring was well advanced, in the deep shade there was nothing but death—rotten leaves, gray and white fungi, and over everything a funereal hush.”

In a bleak era, Miss Lonelyhearts went farther than any novel in its contemplation of despair. The novel is, in fact, the purest expression of despair that American literature has produced, in any era. But it’s not all bad news. Art may provide no consolation in the final reckoning, but it still gives us our best chance to make sense of what Doyle calls “the whole stinking business.” In dark times, Miss Lonelyhearts shines the brightest light in the blackest places. For this reason West’s novel has never felt more alive than today.

Other notable novels published in 1933:

God’s Little Acre by Erskine CaldwellImitation of Life by Fannie HurstBanana Bottom by Claude McKayAnn Vickers by Sinclair LewisThe Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas by Gertrude Stein

Pulitzer Prize:

The Store by T.S. Stribling

Bestselling novel of the year:

Anthony Adverse by Hervey Allen

About this series:

This monthly series will chronicle the history of the American century as seen through the eyes of its novelists. The goal is to create a literary anatomy of the last century—or, to be precise, from 1900 to 2013. In each column I’ll write about a single novel and the year it was published. The novel may not be the bestselling book of the year, the most praised, or the most highly awarded—though awards do have a way of fixing an age’s conventional wisdom in aspic. The idea is to choose a novel that, looking back from a safe distance, seems most accurately, and eloquently, to speak for the time in which it was written. Other than that there are few rules. I won’t pick any stinkers.

Previous Selections:

1902—Brewster’s Millions by George Barr McCutcheon 1912—The Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man by James Weldon Johnson1922—Babbitt by Sinclair Lewis 1932—Tobacco Road by Erskine Caldwell 1942—A Time to Be Born by Dawn Powell 1952—Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison 1962—One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest by Ken Kesey 1972—The Stepford Wives by Ira Levin1982—The Mosquito Coast by Paul Theroux1992—Clockers by Richard Price2002—Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides2012—Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk by Ben Fountain1903—The Call of the Wild by Jack London1913—O Pioneers! By Willa Cather1923—Black Oxen by Gertrude Atherton