If only there were a Republican on the ticket who could combine the pro-business boosterism of Mitt Romney:

“What we need first, last, and all the time is a good, sound business administration!”

with the prideful anti-elitism of Rick Santorum:

“Irresponsible teachers and professors are the worst [menace to sound government], and I am ashamed to say that several of them are on the faculty of our great State University!”

and the union-busting zeal of Newt Gingrich:

“There oughtn’t to be any unions allowed at all; and as it’s the best way of fighting the unions, every business man ought to belong to an employers’-association and to the Chamber of Commerce.”

If only we had a man like George F. Babbitt!

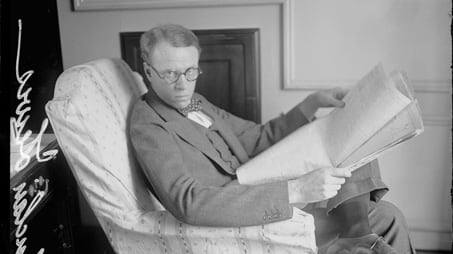

Such a man does exist of course, but only in the pages of the 1922 novel by America’s first Nobel Laureate, Sinclair Lewis. Though Babbitt turns ninety this year, Georgie Babbitt still lives and breathes and harrumphs. It’s impossible this primary season to read a newspaper or turn on the television without hearing the echo of his voice. Babbitt is the original American everyman. By day he is “busier than a bird-dog, not wasting a lot of good time in day-dreaming or going to sassiety teas or kicking about things that are none of his business, but putting the zip into some store or profession or art.” Afternoons “he mows the lawn, or sneaks in some practice putting” and after a terse dinner with wife and kids, he goes to bed, “conscience clear, having contributed his mite to the prosperity of the city and to his own bank-account.” There are lonely moments when, in the middle of the night, he is visited by a mysterious fairy child who promises to whisk him away to foreign worlds “more romantic than scarlet pagodas by a silver sea”—but upon awaking he brusquely wipes such alarming images out of his head and consoles himself with thoughts of carburetors and electric cigar lighters.

A real estate agent in the fictional Midwestern city of Zenith, population 361,000 (“or practically 362,000”), Babbitt is obsessed with his standing in the community, and Zenith’s standing in the world. He takes beaming satisfaction from his association with prominent local figures—like the newspaper poet, T. Cholmondeley “Chum” Frink—and joins every civic association that will accept him: the State Association of Real Estate Boards, the Rotary Club, the Brotherly and Protective Order of Elks, the Outing Golf and Country Club, the Athletic Club (which is neither athletic nor a club), and, most triumphantly of all, the Zenith Boosters’ Club. He is not a member of the Anti-Birth-Control Union, but his priest is. The Presbyterian Church determines his religious beliefs, while the senators who control the Republican Party decide what he should think about war, taxes, and the state of the economy. The large national advertisers fix what he believes to be his individuality: “Toothpastes, socks, tires, cameras, instantaneous hot-water heaters were his symbols and proofs of excellence; at first the signs, then the substitutes, for joy and passion and wisdom.”

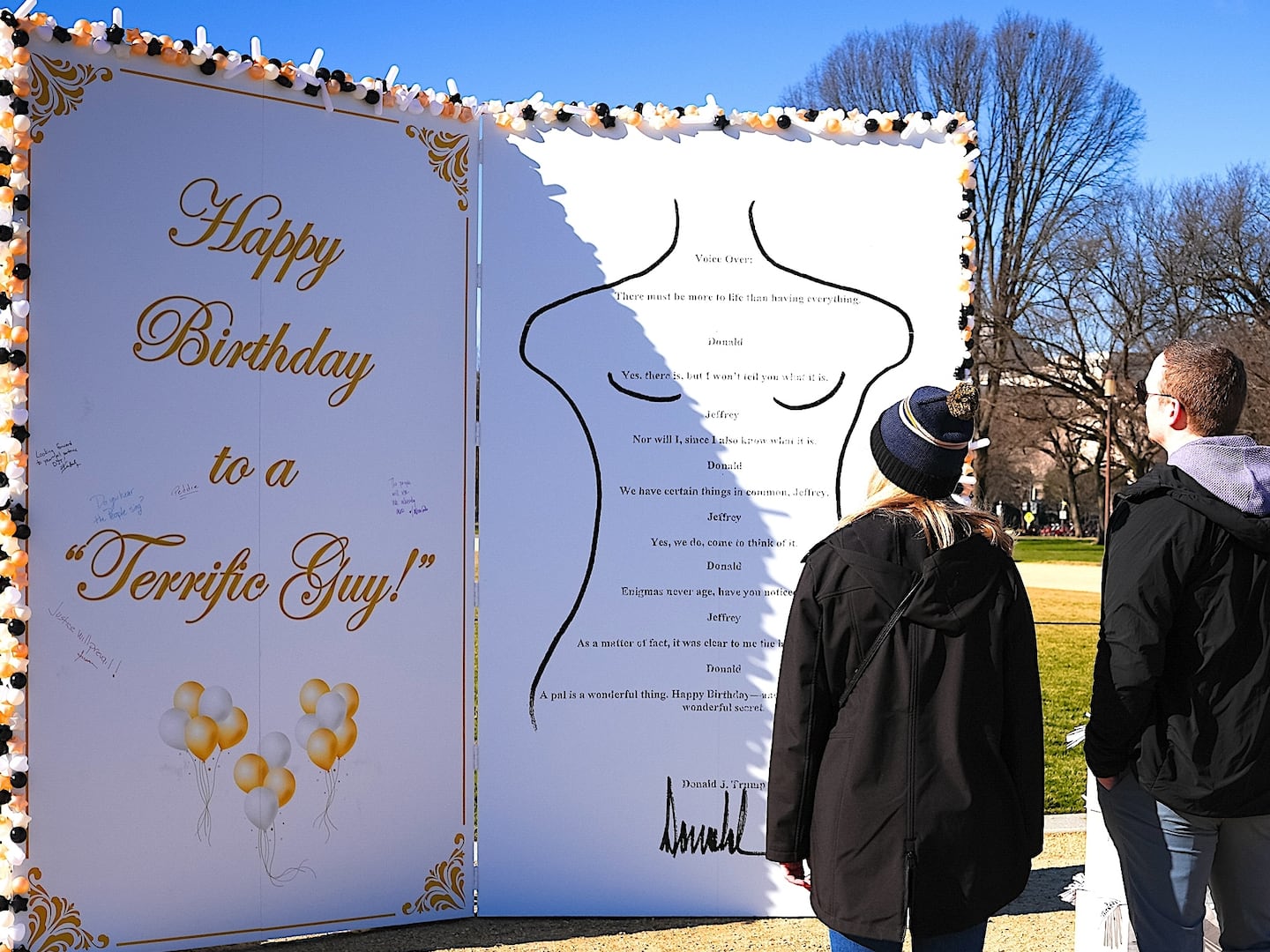

Lewis’s novel is remembered more for its wisdom than its passion. But its wisdom hasn’t always worn well. Thomas Frank, in his excellent 1997 Baffler essay “Babbitt Rex,” called the novel “a strangely limited satire—easy, even for those who inhabit the same social and regional place as George F. Babbitt, to regard as a document strictly of its time.” Frank’s point is that the satire is harmless, itself a form of Babbittry. After all, even good old Uncle George himself has a crisis of faith, and flirts with political moderation and rebellious thoughts before returning to his old chums in the Good Citizens’ League. The novel’s enthusiastic reception in 1922 would seem to support this point. An astonishing 1.6 million copies were sold, many to the same small-town businessmen that Lewis so bitterly lampooned. “Babbitt” and “babbittry” became common nouns. (Much like the term “Main Street,” taken from the title of Lewis’s previous novel; hardly a political speech passes today without its unironic invocation.) Various Midwestern cities claimed to be the real Zenith, and countless citizens declared that they were the real George F. Babbitt. They were in on the joke.

But perhaps there was more to it than a joke. The most startling thing about Babbitt today is not its satire but the haunting, if brief, moments of introspection. In one scene Babbitt, with a sudden hideous glimmer, becomes conscious of his own mortality. His way of life, he realizes, is incredibly mechanical—a mechanical job, mechanical relationships, mechanical conversations, and a mechanical religion, “as inhumanly respectable as a top-hat.” What, Babbitt wonders in another quiet moment, is it all about? What does he want? “Wealth? Social position? Travel? Servants? Yes, but only incidentally.”

In these moments, and in others when he begins to become horrified by his marriage, dulled by years of inanition, it’s possible to make out the primordial shape of novels that would come decades later—novels like Evan S. Connell’s Mrs. Bridge and Mr. Bridge, Sloan Wilson’s The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, and most everything by Richard Yates. The moments of despair in Babbitt are startling because so much of the novel, unlike its successors, is a comedy, played for laughs.

Some of the laughs, however, catch in the throat. In the novel’s final act, Babbitt tries to escape his fate. He takes a mistress, the terribly sophisticated window Tanis Judique, and attends wild alcoholic dance parties (this was the Prohibition era). He develops treasonous opinions. He defends striking workers, questions the sanctity of the Presbyterian Church, and has the temerity to speak up, in the company of his fellow Boosters, for the plight of foreign immigrants. (“Gosh,” says Babbitt, “they aren’t all ignorant, and I got a hunch we’re all descended from immigrants ourselves.”) But his timid foray into critical thinking brings swift and severe punishment. A whisper campaign begins, and soon Babbitt finds himself blacklisted from Zenith society. He loses business contracts and can’t show his face at the Athletic Club. Babbitt is cornered in his office, threatened, and ostracized; his friends turn into menacing henchmen. Terrified, he at last returns, with relief, to mindlessness.

Lewis would pursue this theme explicitly in It Can’t Happen Here, his 1935 novel about an America succumbing to a populist dictator, but already in Babbitt his message was plain. A democracy that demands “a wholesome sameness of thought, dress, painting, morals, and vocabulary” is no democracy, and that is no joke.

Other notable novels published in 1922:

The Beautiful and Damned by F. Scott FitzgeraldGargoyles by Ben Hecht Gentle Julia by Booth Tarkington Hungry Hearts by Anzia YezierskaGlimpses of the Moon by Edith Wharton

Pulitzer Prize:

One of Ours by Willa Cather

Bestselling novel of the year:

If Winter Comes by A.S.M. Hutchinson

This monthly series will chronicle the history of the American century as seen through the eyes of its novelists. The goal is to create a literary anatomy of the last century—or, to be precise, from 1900 to 2012. In each column I’ll write about a single novel and the year it was published. The novel may not be the bestselling book of the year, the most praised, or the most highly awarded—though awards do have a way of fixing an age’s conventional wisdom in aspic. The idea is to choose a novel that, looking back from a safe distance, seems most accurately, and eloquently, to speak for the time in which it was written. Other than that there are few rules. I won’t pick any stinkers.

Previous selections:

1902—Brewster’s Millions by George Barr McCutcheon1912—The Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man by James Weldon Johnson